Related Research Articles

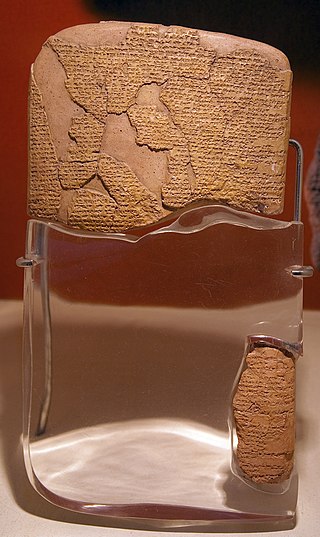

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement concluded by sovereign states in international law. International organizations can also be party to an international treaty. A treaty is binding under international law.

The Ojibwe are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland covers much of the Great Lakes region and the northern plains, extending into the subarctic and throughout the northeastern woodlands. Ojibweg, being Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands and of the subarctic, are known by several names, including Ojibway or Chippewa. As a large ethnic group, several distinct nations also consider themselves Ojibwe, including the Saulteaux, Nipissings, and Oji-Cree.

The Saulteaux, otherwise known as the Plains Ojibwe, are a First Nations band government in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia, Canada. They are a branch of the Ojibwe who pushed west. They formed a mixed culture of woodlands and plains Indigenous customs and traditions.

Trent University is a public liberal arts university in Peterborough, Ontario, with a satellite campus in Oshawa, which serves the Regional Municipality of Durham. Trent is known for its Oxbridge college system and small class sizes.

The Mississaugas are a group of First Nations peoples located in southern Ontario, Canada. They are a sub-group of the Ojibwe Nation.

The Anishinaabe are a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples in the Great Lakes region of Canada and the United States. They include the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, Mississaugas, Nipissing, and Algonquin peoples. The Anishinaabe speak Anishinaabemowin, or Anishinaabe languages that belong to the Algonquian language family.

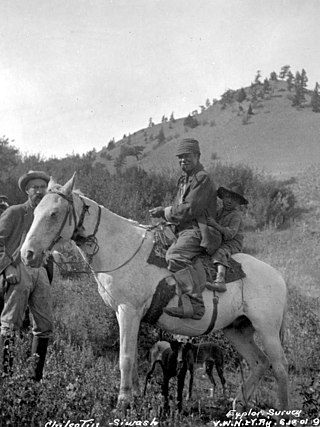

The Tsilhqotʼin or Chilcotin are a North American tribal government of the Athabaskan-speaking ethnolinguistic group that live in what is now known as British Columbia, Canada. They are the most southern of the Athabaskan-speaking Indigenous peoples in British Columbia.

Harold Cardinal was a Cree writer, political leader, teacher, negotiator, and lawyer. Throughout his career he advocated, on behalf of all First Nation peoples, for the right to be "the red tile in the Canadian mosaic."

The Robinson Treaties are two treaties signed between the Ojibwa chiefs and the Crown in 1850 in the Province of Canada. The first treaty involved Ojibwa chiefs along the north shore of Lake Superior, and is known as the Robinson Superior Treaty. The second treaty, signed two days later, included Ojibwa chiefs from along the eastern and northern shores of Lake Huron, and is known as the Robinson Huron Treaty. The Wiikwemkoong First Nation did not sign either treaty, and their land is considered "unceded".

Curve Lake First Nation is a Mississauga Ojibway First Nation located in Peterborough County of Ontario. Curve Lake First Nation occupies three reserves; Curve Lake First Nation 35, Curve Lake 35A, and Islands in the Trent Waters Indian Reserve 36A. The last of these reserves is shared with the Hiawatha First Nation and the Scugog First Nation. Curve Lake First Nation has a registered membership of 2,415 as of October 2019 with 793 registered band members living in Curve Lake and an additional 1,622 registered band members living off-reserve.

Chippewas of Rama First Nation, also known as Chippewas of Mnjikaning and Chippewas of Rama Mnjikaning First Nation, is an Anishinaabe (Ojibway) First Nation located in the province of Ontario in Canada. The name Mnjikaning, or fully vocalized as Minjikaning, refers to the fishing weirs at Atherley Narrows between Lake Simcoe and Lake Couchiching and it means "in/on/at or near the fence".

The Hiawatha First Nation is a Mississauga Ojibwe First Nations reserve located on the north shore of Rice Lake east of the Otonabee River in Ontario, Canada.

Burleigh Falls is both a geological feature and a small community in Peterborough County, Ontario, Canada. The falls form the boundary between the municipality of North Kawartha to the north and the municipality of Selwyn to the south.

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson is a Mississauga Nishnaabeg writer, musician, and academic from Canada. She is also known for her work with Idle No More protests. Simpson is a faculty member at the Dechinta Centre for Research and Learning. She lives in Peterborough.

A Dish With One Spoon, also known as One Dish One Spoon, is a law used by Indigenous peoples of the Americas since at least 1142 CE to describe an agreement for sharing hunting territory among two or more nations. People are all eating out of the single dish, that is, all hunting in the shared territory. One spoon signifies that all Peoples sharing the territory are expected to limit the game they take to leave enough for others, and for the continued abundance and viability of the hunting grounds into the future. Sometimes the Indigenous language word is rendered in English as bowl or kettle rather than dish.

The Big River First Nation is a part of the Cree Nation and is located in the Saskatchewan province of Canada. The Big River First Nation is also called ᒥᐢᑕᐦᐃ ᓰᐲᕁ mistahi-sîpîhk in Cree meaning "at the big river". They are signatories of Treaty 6 are located close to Pelican Lake Ojibway, the Big River and Prince Albert National Park. They are 120 km northwest of the city of Prince Albert and 19 km southwest of the village of Debden. The Big River First Nation has nearly 30,000 acres of reserve land. Their reserves include-

Indigenous law in Canada refers to the legal traditions, customs, and practices of Indigenous peoples and groups. Canadian aboriginal law is different from Indigenous Law. Canadian Aboriginal law provides certain constitutionally recognized rights to land and traditional practices.

Indigenous cultures in North America engage in storytelling about morality, origin, and education as a form of cultural maintenance, expression, and activism. Falling under the banner of oral tradition, it can take many different forms that serve to teach, remember, and engage Indigenous history and culture. Since the dawn of human history, oral stories have been used to understand the reasons behind human existence. Today, Indigenous storytelling is part of the broader indigenous process of building and transmitting indigenous knowledge.

Olivia Whetung is a contemporary artist, printmaker, writer, and member of the Curve Lake First Nation and citizen of the Nishnaabeg Nation.

Indigenous resurgence is a transformative movement of resistance and decolonization. The practice of Indigenous resurgence is a form of regenerative nation-building and reconnection with all their relations. It constitutes kin-centric relationships among BIPOC peoples and with the natural world.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Trent University Mourns the Passing of Doug Williams (Gidigaa Migizi)". Trent University News. 2022-07-14. Retrieved 2023-12-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Williams, Doug (2018). Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg: This Is Our Territory. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Arbeiter Ring Publishing. ISBN 978-1-927886-09-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Remembering the life of Douglas WILLIAMS". obituaries.thepeterboroughexaminer.com. Retrieved 2023-12-02.

- 1 2 "Trent University's Newest College to be Named Gidigaa Migizi in Honour of Beloved Elder and Professor Doug Williams". Trent University News. 2023-11-15. Retrieved 2023-12-02.

- 1 2 Reporter, Brendan Burke Local Journalism Initiative (2022-07-14). "'A great leader:' Curve Lake Elder Douglas Williams remembered as kind and generous knowledge-keeper". The Peterborough Examiner. Retrieved 2023-12-02.

- 1 2 Rellinger, Paul (2022-07-13). "Curve Lake First Nation, Trent University mourn passing of Elder Douglas Williams (Gidigaa Migizi)". kawarthaNOW. Retrieved 2023-12-02.