Related Research Articles

In physics, theBardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) theory is the first microscopic theory of superconductivity since Heike Kamerlingh Onnes's 1911 discovery. The theory describes superconductivity as a microscopic effect caused by a condensation of Cooper pairs. The theory is also used in nuclear physics to describe the pairing interaction between nucleons in an atomic nucleus.

Condensed matter physics is the field of physics that deals with the macroscopic and microscopic physical properties of matter, especially the solid and liquid phases, that arise from electromagnetic forces between atoms and electrons. More generally, the subject deals with condensed phases of matter: systems of many constituents with strong interactions among them. More exotic condensed phases include the superconducting phase exhibited by certain materials at extremely low cryogenic temperatures, the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic phases of spins on crystal lattices of atoms, the Bose–Einstein condensates found in ultracold atomic systems, and liquid crystals. Condensed matter physicists seek to understand the behavior of these phases by experiments to measure various material properties, and by applying the physical laws of quantum mechanics, electromagnetism, statistical mechanics, and other physics theories to develop mathematical models and predict the properties of extremely large groups of atoms.

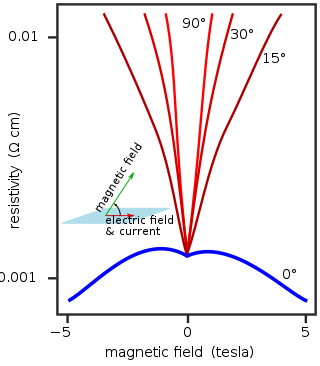

Superconductivity is a set of physical properties observed in certain materials where electrical resistance vanishes and magnetic fields are expelled from the material. Any material exhibiting these properties is a superconductor. Unlike an ordinary metallic conductor, whose resistance decreases gradually as its temperature is lowered, even down to near absolute zero, a superconductor has a characteristic critical temperature below which the resistance drops abruptly to zero. An electric current through a loop of superconducting wire can persist indefinitely with no power source.

Heike Kamerlingh Onnes was a Dutch physicist and Nobel laureate. He exploited the Hampson–Linde cycle to investigate how materials behave when cooled to nearly absolute zero and later to liquefy helium for the first time, in 1908. He also discovered superconductivity in 1911.

Liquid helium is a physical state of helium at very low temperatures at standard atmospheric pressures. Liquid helium may show superfluidity.

Superconductivity is the phenomenon of certain materials exhibiting zero electrical resistance and the expulsion of magnetic fields below a characteristic temperature. The history of superconductivity began with Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes's discovery of superconductivity in mercury in 1911. Since then, many other superconducting materials have been discovered and the theory of superconductivity has been developed. These subjects remain active areas of study in the field of condensed matter physics.

A quantum critical point is a point in the phase diagram of a material where a continuous phase transition takes place at absolute zero. A quantum critical point is typically achieved by a continuous suppression of a nonzero temperature phase transition to zero temperature by the application of a pressure, field, or through doping. Conventional phase transitions occur at nonzero temperature when the growth of random thermal fluctuations leads to a change in the physical state of a system. Condensed matter physics research over the past few decades has revealed a new class of phase transitions called quantum phase transitions which take place at absolute zero. In the absence of the thermal fluctuations which trigger conventional phase transitions, quantum phase transitions are driven by the zero point quantum fluctuations associated with Heisenberg's uncertainty principle.

In materials science, heavy fermion materials are a specific type of intermetallic compound, containing elements with 4f or 5f electrons in unfilled electron bands. Electrons are one type of fermion, and when they are found in such materials, they are sometimes referred to as heavy electrons. Heavy fermion materials have a low-temperature specific heat whose linear term is up to 1000 times larger than the value expected from the free electron model. The properties of the heavy fermion compounds often derive from the partly filled f-orbitals of rare-earth or actinide ions, which behave like localized magnetic moments.

Ferromagnetic superconductors are materials that display intrinsic coexistence of ferromagnetism and superconductivity. They include UGe2, URhGe, and UCoGe. Evidence of ferromagnetic superconductivity was also reported for ZrZn2 in 2001, but later reports question these findings. These materials exhibit superconductivity in proximity to a magnetic quantum critical point.

The 122 iron arsenide unconventional superconductors are part of a new class of iron-based superconductors. They form in the tetragonal I4/mmm, ThCr2Si2 type, crystal structure. The shorthand name "122" comes from their stoichiometry; the 122s have the chemical formula AEFe2Pn2, where AE stands for alkaline earth metal (Ca, Ba Sr or Eu) and Pn is pnictide (As, P, etc.). These materials become superconducting under pressure and also upon doping. The maximum superconducting transition temperature found to date is 38 K in the Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2. The microscopic description of superconductivity in the 122s is yet unclear.

Piers Coleman is a British-born theoretical physicist, working in the field of theoretical condensed matter physics. Coleman is professor of physics at Rutgers University in New Jersey and at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Heavy fermion superconductors are a type of unconventional superconductor.

In condensed matter physics, a quantum spin liquid is a phase of matter that can be formed by interacting quantum spins in certain magnetic materials. Quantum spin liquids (QSL) are generally characterized by their long-range quantum entanglement, fractionalized excitations, and absence of ordinary magnetic order.

In condensed matter physics, quantum oscillations describes a series of related experimental techniques used to map the Fermi surface of a metal in the presence of a strong magnetic field. These techniques are based on the principle of Landau quantization of Fermions moving in a magnetic field. For a gas of free fermions in a strong magnetic field, the energy levels are quantized into bands, called the Landau levels, whose separation is proportional to the strength of the magnetic field. In a quantum oscillation experiment, the external magnetic field is varied, which causes the Landau levels to pass over the Fermi surface, which in turn results in oscillations of the electronic density of states at the Fermi level; this produces oscillations in the many material properties which depend on this, including resistance, Hall resistance, and magnetic susceptibility. Observation of quantum oscillations in a material is considered a signature of Fermi liquid behaviour.

CeCoIn5 ("Cerium-Cobalt-Indium 5") is a heavy-fermion superconductor with a layered crystal structure, with somewhat two-dimensional electronic transport properties. The critical temperature of 2.3 K is the highest among all of the Ce-based heavy-fermion superconductors.

Chiral magnetic effect (CME) is the generation of electric current along an external magnetic field induced by chirality imbalance. Fermions are said to be chiral if they keep a definite projection of spin quantum number on momentum. The CME is a macroscopic quantum phenomenon present in systems with charged chiral fermions, such as the quark–gluon plasma, or Dirac and Weyl semimetals. The CME is a consequence of chiral anomaly in quantum field theory; unlike conventional superconductivity or superfluidity, it does not require a spontaneous symmetry breaking. The chiral magnetic current is non-dissipative, because it is topologically protected: the imbalance between the densities of left-handed and right-handed chiral fermions is linked to the topology of fields in gauge theory by the Atiyah-Singer index theorem.

UPd2Al3 is a heavy-fermion superconductor with a hexagonal crystal structure and critical temperature Tc=2.0K that was discovered in 1991. Furthermore, UPd2Al3 orders antiferromagnetically at TN=14K, and UPd2Al3 thus features the unusual behavior that this material, at temperatures below 2K, is simultaneously superconducting and magnetically ordered. Later experiments demonstrated that superconductivity in UPd2Al3 is magnetically mediated, and UPd2Al3 therefore serves as a prime example for non-phonon-mediated superconductors.

Pengcheng Dai is a Chinese American experimental physicist and academic. He is the Sam and Helen Worden Professor of Physics in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Rice University.

Elbio Rubén Dagotto is an Argentinian-American theoretical physicist and academic. He is a distinguished professor in the department of physics and astronomy at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and Distinguished Scientist in the Materials Science and Technology Division at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

In physics, the Matthias rules refers to a historical set of empirical guidelines on how to find superconductors. These rules were authored Bernd T. Matthias who discovered hundreds of superconductors using these principles in the 1950s and 1960s. Deviations from these rules have been found since the end of the 1970s with the discovery of unconventional superconductors.

References

- 1 2 "Preisverleihungen 1991". Phys. Bl. 47: 230. 1991. doi: 10.1002/phbl.19910470317 .

- 1 2 3 4 "Department of Physics, Cavendish Laboratory". University of Cambridge, Department of Physics. Archived from the original on 6 October 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- 1 2 Pfleiderer, C.; McMullan, G.J.; Julian, S.R.; Lonzarich, G.G. (1997). "Magnetic quantum phase transition in MnSi under hydrostatic pressure". Phys. Rev. B. 55 (13): 8330–8338. Bibcode:1997PhRvB..55.8330P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.55.8330.

- 1 2 Mathur, N.D.; Grosche, F.M.; Julian, S.R.; Walker, I.R.; Freye, D.M.; Haselwimmer, R.K.W.; Lonzarich, G.G. (1998). "Magnetically mediated superconductivity in heavy fermion compounds". Nature. 394 (6688): 39–43. Bibcode:1998Natur.394...39M. doi:10.1038/27838. S2CID 52837444.

- 1 2 Taillefer, L.; Lonzarich, G.G. (1988). "Heavy-fermion quasiparticles in UPt3". Phys. Rev. Lett. 60 (15): 1570–1573. Bibcode:1988PhRvL..60.1570T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.60.1570. PMID 10038074.

- ↑ Rowley, S.E.; Spalek, L.J.; Smith, R.P.; Dean, M.P.M.; Itoh, M.; Scott, J.F.; Lonzarich, G.G.; Saxena, S.S. (2014). "Ferroelectric quantum criticality". Nature Physics. 10 (5): 367–372. arXiv: 0903.1445 . Bibcode:2014NatPh..10..367R. doi:10.1038/nphys2924. S2CID 120096268.

- 1 2 Gibney, E. (2017). "A quantum pioneer unlocks matter's hidden secrets". Nature. 549 (7673): 448–450. Bibcode:2017Natur.549..448G. doi: 10.1038/549448a .

- ↑ "Kamerlingh Onnes Prize". M2S Conference 2015. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2017.