Related Research Articles

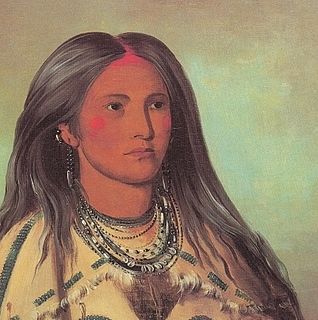

The Crow, whose autonym is Apsáalooke, also spelled Absaroka, are Native Americans living primarily in southern Montana. Today, the Crow people have a federally recognized tribe, the Crow Tribe of Montana, with an Indian reservation located in the south-central part of the state.

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox states that "the study of kinship is the study of what man does with these basic facts of life – mating, gestation, parenthood, socialization, siblingship etc." Human society is unique, he argues, in that we are "working with the same raw material as exists in the animal world, but [we] can conceptualize and categorize it to serve social ends." These social ends include the socialization of children and the formation of basic economic, political and religious groups.

The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, also known as the Three Affiliated Tribes, is a Native American Nation resulting from the alliance of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara peoples, whose native lands ranged across the Missouri River basin extending from present day North Dakota through western Montana and Wyoming.

The Hidatsa are a Siouan people. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. Their language is related to that of the Crow, and they are sometimes considered a parent tribe to the modern Crow in Montana.

Arikara, also known as Sahnish, Arikaree, Ree, or Hundi, are a tribe of Native Americans in North Dakota. Today, they are enrolled with the Mandan and the Hidatsa as the federally recognized tribe known as the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.

Mandan is an extinct Siouan language of North Dakota in the United States.

The Mandan are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived for centuries primarily in what is now North Dakota. They are enrolled in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan still reside in the area of the reservation; the rest reside around the United States and in Canada.

Robert Harry Lowie was an Austrian-born American anthropologist. An expert on North American Indians, he was instrumental in the development of modern anthropology.

Like-a-Fishhook Village was a Native American settlement next to Fort Berthold in North Dakota, established by dissident bands of the Three Affiliated Tribes, the Mandan, Arikara and Hidatsa. Formed in 1845, it was also eventually inhabited by non-Indian traders, and became important in the trade between Natives and non-Natives in the region.

Frances Theresa Densmore was an American anthropologist and ethnographer born in Red Wing, Minnesota. Densmore is known for her studies of Native American music and culture, and in modern terms, she may be described as an ethnomusicologist.

Dan Sperber is a French social and cognitive scientist. His most influential work has been in the fields of cognitive anthropology and linguistic pragmatics: developing, with British psychologist Deirdre Wilson, relevance theory in the latter; and an approach to cultural evolution known as the epidemiology of representations in the former. Sperber currently holds the positions of Directeur de Recherche émérite at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and Director of the International Cognition and Culture Institute.

Waheenee, also referred to as the Buffalo Bird Woman was a traditional Hidatsa woman who lived on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. Her Hidatsa name was Waheenee, though she was also called Maaxiiriwia. She was known for maintaining the traditional lifestyle of the Hidatsa, including gardening, cooking, and household tasks. She passed on the traditional ways of her culture and oral tradition through interviews with Gilbert Wilson, in which she described her own experience and the lives and work of Hidatsa women.

Harold K. (Hal) Schneider (1925–1987), a seminal figure in economic anthropology, was born in 1925, in Aberdeen, South Dakota. He attended elementary and secondary school in St. Paul, Minnesota, and did his undergraduate work at Macalester College and Seabury-Western Theological Seminary, receiving a bachelor's degree in sociology, with a minor in biology, from Macalester in 1949. He then went to Northwestern University, where he was a student of Melville Herskovits, basing his dissertation on field research among the Pokot of Kenya.

Sacagawea was a Lemhi Shoshone woman who, at age 16, met and helped the Lewis and Clark Expedition in achieving their chartered mission objectives by exploring the Louisiana Territory. Sacagawea traveled with the expedition thousands of miles from North Dakota to the Pacific Ocean, helping to establish cultural contacts with Native American populations and contributing to the expedition's knowledge of natural history in different regions.

Curt Unckel Nimuendajú was a German-Brazilian ethnologist, anthropologist, and writer. His works are fundamental for the understanding of the religion and cosmology of some native Brazilian Indians, especially the Guaraní people. He received the surname "Nimuendajú" from the Apapocuva subgroup of the Guaraní people, meaning "the one who made himself a home", one year after living among them. Upon taking Brazilian citizenship in 1922, he officially added the Nimuendajú as one of his surnames. On his obituary, his Brazilian-German colleague Herbert Baldus called him "perhaps the greatest Indianista of all time".

Jan Petrus Benjamin de Josselin de Jong was a founding father of modern Dutch anthropology and of structural anthropology at Leiden University.

Kinnikinnick is a Native American and First Nations herbal smoking mixture, made from a traditional combination of leaves or barks. Recipes for the mixture vary, as do the uses, from social, to spiritual to medicinal.

The White Buffalo Cow Society has historically been the most respected women's society amongst the Mandan and Hidatsa peoples. The women of the White Buffalo Cow Society perform the buffalo-calling ceremony. Modern societies dedicated to White Buffalo Calf Woman are often dedicated to protection of women and children from rape and domestic violence.

Janet D. Spector was an American archaeologist known for her contributions to the archaeology of gender and ethnoarchaeology. An influential paper she co-wrote in 1984 entitled "Archaeology and the Study of Gender" is considered to be the beginning of feminist archaeology. She is also the author of the 1993 book What This Awl Means: Feminist Archaeology at a Wahpeton Dakota Village, which combines Spector's autobiography with the excavation of the Little Rapids site in Scott County, Minnesota and a fictional story of a young Dakota woman who lived in the village. The book was revolutionary in its attempt at a task differentiation framework and it’s intersectional approach to ethnography with indigenous and gendered perspectives at the forefront. She earned her bachelor's, master's, and PHD degrees at the University of Wisconsin.Her lifelong experiences in archaeological fieldwork began her sophomore year of her undergrad and included sites in Wisconsin, Minnesota, Israel, and Canada. While completing her PHD she began her career as a professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Minnesota. In her 25 years there she helped found the women's studies program and chaired the program from 1981 to 1984. She was also awarded the Horace T Morse University of Minnesota Alumni Association Award for Outstanding Contributions to Undergraduate Education in 1986. Other noteworthy accolades from her time as a faculty member include her role as assistant provost where she chaired a Commission on Women and penned the Minnesota Plan II, as well as her hand in founding the Center for Advanced Feminist Studies. Outside of the university she served on the advisory board for the American Anthropological Association's project on “Gender and Archaeology” from 1986-1988 where she co-wrote an essay on "Incorporating Gender into Archaeology Courses" that was designed to bring feminist anthropology into the classroom. In 1998 she presented her essay "Reminiscence" at the "Doing Archaeology as a Feminist" seminar at the School for Advanced Research.

Agriculture on the prehistoric Great Plains describes the agriculture of the Indian peoples of the Great Plains of the United States and southern Canada in the Pre-Columbian era and before extensive contact with European explorers, which in most areas occurred by 1750. The principal crops grown by Indian farmers were maize (corn), beans, and squash, including pumpkins. Sunflowers, goosefoot, tobacco, gourds, and plums, were also grown.

References

- Baker, Gerard. 1987. The Hidatsa Religious Experience. In The Way to Independence. Ed. Carolyn Gilman & Mary Jane Schneider. Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN.

- Gilman, Carolyn & Mary Jane Schneider. 1987. Wolf Chief Sells the Shrine. In The Way to Independence. Ed. Carolyn Gilman & Mary Jane Schneider. Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN.

- Goodbird, Edward. 1914. Goodbird the Indian: His Story, Told by Himself to Gilbert L. Wilson. Illus. Frederick N. Wilson. Fleming H. Revell, New York, NY. Reprint Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul, MN. 1985.

- Lowie, Robert, H. 1959. Robert H. Lowie: Ethnologist: A Personal Record. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

- Maxidiwiac. 1921. Waheenee: an Indian Girl’s Story: Told by Herself to Gilbert L. Wilson, Ph.D. Illus. Frederick N. Wilson. Webb Publishing Co., St. Paul, MN.

- Schneider, Mary Jane. 1985. Introduction. In Goodbird the Indian: His Story, Told by Himself to Gilbert L. Wilson. Illus. Frederick N. Wilson. Fleming H. Revell, New York, NY. Reprint Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul, MN. 1985.

- Woolworth, Alan, R. 1987. Contributions of the Wilsons to the Study of the Hidatsa. In The Way to Independence. Ed. Carolyn Gilman & Mary Jane Schneider. Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN.