Uruk, known today as Warka, was an ancient city in the Near East, located east of the current bed of the Euphrates River, on an ancient, now-dried channel of the river. The site lies 93 kilometers northwest of ancient Ur, 108 kilometers southeast of ancient Nippur, and 24 kilometers southeast of ancient Larsa. It is 30 km (19 mi) east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthannā, Iraq.

Shu-turul was the last king of the Akkadian Empire, ruling for 15 years according to the Sumerian king list. It indicates that he succeeded his father Dudu. A few artifacts, seal impressions etc. attest that he held sway over a greatly reduced Akkadian territory that included Kish, Tutub, Nippur, and Eshnunna. The Diyala river also bore the name "Shu-durul" at the time.

Shuruppak, modern Tell Fara, was an ancient Sumerian city situated about 55 kilometres (35 mi) south of Nippur and 30 kilometers north of ancient Uruk on the banks of the Euphrates in Iraq's Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate. Shuruppak was dedicated to Ninlil, also called Sud, the goddess of grain and the air.

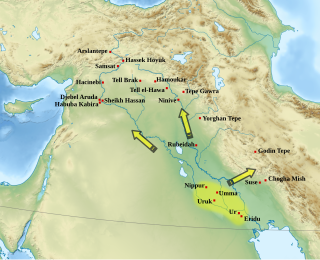

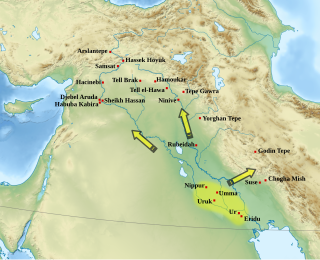

The Uruk period existed from the protohistoric Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period in the history of Mesopotamia, after the Ubaid period and before the Jemdet Nasr period. Named after the Sumerian city of Uruk, this period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia and the Sumerian civilization. The late Uruk period saw the gradual emergence of the cuneiform script and corresponds to the Early Bronze Age; it has also been described as the "Protoliterate period".

Theodor Wiegand was a German archaeologist.

The German Archaeological Institute is a research institute in the field of archaeology. The DAI is a "federal agency" under the Federal Foreign Office of Germany.

Kisurra was an ancient Sumerian tell situated on the west bank of the Euphrates, 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) north of Shuruppak and due east of Kish.

Albert Grünwedel was a German Indologist, Tibetologist, archaeologist, and explorer of Central Asia. He was one of the first scholars to study the Lepcha language.

Tell Chuera is an ancient Near Eastern tell site in Raqqa Governorate, northern Syria. It lies between the Balikh and Khabur rivers.

Tuttul was an ancient Near East city. Tuttul is identified with the archaeological site of Tell Bi'a in Raqqa Governorate, Syria. Tell Bi'a is located near the modern city of Raqqa and at the confluence of the rivers Balikh and Euphrates.

The Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, abbreviated DOG, is a German voluntary association based in Berlin dedicated to the study of the Near East.

Tall Munbāqa or Mumbaqat, the site of the Late Bronze Age city of Ekalte, is a 5,000-year-old town complex in northern Syria now lying in ruins.

Theodor Friedrich Heinrich von Lüpke was a German architectural historian known for his work in the field of photogrammetry.

Alfred Brueckner was a German classical archaeologist. He was a specialist in Greek funerary art.

Antigonus, son of Menophilus was a Seleucid official (nauarchos). He served under king Alexander, in the mid-2nd century BC. He is known from an inscription found in the city of Miletus.

Matthias Untermann is a German art historian and medieval archaeologist.

Sirkeli Höyük is one of the largest tells of Cilicia with an area of approximately 80 ha. It is 40 kilometers east of the city of Adana, northwest of the village Sirkeli in the district of Ceyhan, at the breakthrough of the Ceyhan through the Misis Mountains.

Tall Bazi, is an ancient Near East archaeological site in Raqqa Governorate of Syria in the same general area as Mari and Ebla. It is located on the east bank of Euphrates river in upper Syria, about 60 kilometers south of Turkey border. It is considered a twin site to the adjacent Tell Banat Complex. Both were occupied in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC with Banat being the focus in the early part and Bazi in the later. Tall Bazi has been proposed as the location of Armanum, known from texts of Sargon and Naram-Sin in the Akkadian period, during the reign of Naram-Sin of Akkad. It was occupied into the Mitanni period, with an occupational gap after c. 2300 BC, at which time it was destroyed. In the Late Roman Empire a large building was constructed at the top of the main mound, using the remaining Late Bronze Age fortification walls.

Julius Johann Heinrich Jordan was a German archaeologist active in Mesopotamia before and after the First World War.

Jebel Aruda, is an ancient Near East archaeological site on the west bank of the Euphrates river in Raqqa Governorate, Syria. It was excavated as part of a program of rescue excavation project for sites to be submerged by the creation of Lake Assad by the Tabqa Dam. The site was occupied in the Late Chalcolithic, during the late 4th millennium BC, specifically in the Uruk V period. It is on the opposite side of the lake from the Halafian site of Shams ed-Din Tannira and is within sight of the Uruk V site Habuba Kabira and thought to have been linked to it. The archaeological sites of Tell es-Sweyhat and Tell Hadidi are also nearby.