The Ubaid period is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially in 1919 by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.

The Kura–Araxes culture was an archaeological culture that existed from about 4000 BC until about 2000 BC, which has traditionally been regarded as the date of its end; in some locations it may have disappeared as early as 2600 or 2700 BC. The earliest evidence for this culture is found on the Ararat plain; it spread north in the Caucasus by 3000 BC.

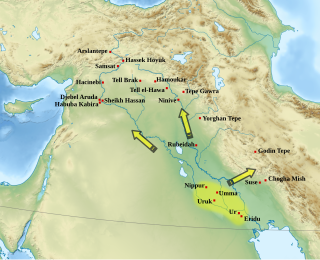

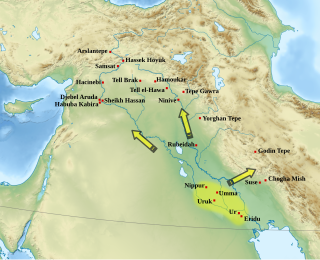

The Uruk period existed from the protohistoric Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period in the history of Mesopotamia, after the Ubaid period and before the Jemdet Nasr period. Named after the Sumerian city of Uruk, this period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia and the Sumerian civilization. The late Uruk period saw the gradual emergence of the cuneiform script and corresponds to the Early Bronze Age; it has also been described as the "Protoliterate period".

The Proto-Elamite period, also known as Susa III, is a chronological era in the ancient history of the area of Elam, dating from c. 3100 BC to 2700 BC. In archaeological terms this corresponds to the late Banesh period. Proto-Elamite sites are recognized as the oldest civilization in Iran. The Proto-Elamite script is an Early Bronze Age writing system briefly in use before the introduction of Elamite cuneiform.

Teppe Hasanlu or Hasanlu Tepe is an archeological site of an ancient city located in northwest Iran, a short distance south of Lake Urmia. The nature of its destruction at the end of the 9th century BC essentially froze one layer of the city in time, providing researchers with extremely well preserved buildings, artifacts, and skeletal remains from the victims and enemy combatants of the attack. The site was likely associated with the Mannaeans.

Tepe Sialk is a large ancient archeological site in a suburb of the city of Kashan, Isfahan Province, in central Iran, close to Fin Garden. The culture that inhabited this area has been linked to the Zayandeh River Culture.

Persian wine, also called May, Mul, and Bâdah, is a cultural symbol and tradition in Iran, and has a significant presence in Iranian mythology, Persian poetry and Persian miniatures.

Tepe Gawra is an ancient Mesopotamian settlement 15 miles NNE of Mosul in northwest Iraq that was occupied between 5000 and 1500 BC. It is roughly a mile from the site of Nineveh and 2 miles E of the site of Khorsabad. It contains remains from the Halaf period, the Ubaid period, and the Uruk period. Tepe Gawra contains material relating to the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period c. 5,500–5,000 BC.

Tapeh Yahya is an archaeological site in Kermān Province, Iran, some 220 kilometres (140 mi) south of Kerman city, 90 kilometres (56 mi) south of Baft city and 90 km south-west of Jiroft. The easternmost occupation of the Proto-Elamite culture was found there.

Hajji Firuz Tepe is an archaeological site located in West Azarbaijan Province in north-western Iran and lies in the north-western part of the Zagros Mountains. The site was excavated between 1958 and 1968 by archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. The excavations revealed a Neolithic village that was occupied in the second half of the sixth millennium BC where some of the oldest archaeological evidence of grape-based wine was discovered in the form of organic residue in a pottery jar.

The Shengavit Settlement is an archaeological site in present-day Yerevan, Armenia located on a hill south-east of Yerevan Lake. It was inhabited during a series of settlement phases from approximately 3000 BC cal to 2500 BC cal in the Kura–Araxes (Shengavitian) period of the Early Bronze Age and irregularly re-used in the Middle Bronze Age until 2200 BC cal. The town occupied an area of six hectares. It appears that Shengavit was a societal center for the areas surrounding the town due to its unusual size, evidence of surplus production of grains, and metallurgy, as well as its monumental 4 meter wide stone wall. Three smaller village sites of Moukhannat Tepe, Khorumbulagh, and Tairov have been identified and were located outside the walls of Shengavit. Its pottery makes it a type site of the Kura-Araxes or Early Transcaucasian Period and the Shengavitian culture area.

Choghā Mīsh (Persian language; چغامیش čoġā mīš) dating back to about 6800 BC, is the site of a Chalcolithic settlement located in the Khuzistan Province Iran on the eastern Susiana Plain. It was occupied at the beginning of 6800 BC and continuously from the Neolithic up to the Proto-Literate period, thus spanning the time periods from Archaic through Proto-Elamite period. After the decline of the site about 4400 BC, the nearby Susa, on the western Susiana Plain, became culturally dominant in this area. Chogha Mish is located just to the east of Dez River, and about 25 kilometers to the east from the ancient Susa. The similar, though much smaller site of Chogha Bonut lies six kilometers to the west.

Tureng Tepe is a Neolithic and Chalcolithic archaeological site in northeastern Iran, in the Gorgan plain, approximately 17 km northeast of the town of Gorgan. Nearby is a village of Turang Tappeh.

Beveled rim bowls are small, undecorated, mass-produced clay bowls most common in the 4th millennium BC during the Late Chalcolithic period. They constitute roughly three quarters of all ceramics found in Uruk culture sites, are therefore a unique and reliable indicator of the presence of the Uruk culture in ancient Mesopotamia.

Bābā Jān Tepe (Tappa), an archeological site in north-eastern Lorestan Province, on the southern edge of the Delfān plain at approximately 10 km from Nūrābād, important primarily for excavations of first-millennium BC levels conducted by C. Goff from 1966-69. Work concentrated on two mounds joined by a saddle. The East Mound yielded a series of first-millennium BC buildings above Bronze Age graves. On the Central Mound, excavation concentrated on the Baba Jan III Manor on the summit; an 8 x 6 m Deep Sounding provides a partial late fourth- to mid-second-millennium BC sequence

Kul Tepe Jolfa is an ancient archaeological site in the Jolfa County of Iran, located in the city of Hadishahr, about 10 km south from the Araxes River.

Dalma culture was a prehistoric archaeological culture of north-western Iran dating to early fifth millennium B.C. Later, it spread into the central Zagros region and elsewhere in adjacent areas. Its widespread ceramic remains were excavated in central and northern valleys of the Zagros Mountains in north-western Iran. Dalma assemblages were initially discovered by the excavations carried out at Dalma Tepe and Hasanlu Tepe in south-western parts of Lake Urmia, in the valley of Solduz.

Bülövaqaya settlement is an archeological site located on the left bank of the Sarisu river, west of Göynük village of Babek district.

Dalma Tepe is an archaeological site about 2km northeast of Naqadeh, Naqadeh County, in the Iranian province of West Azerbaijan. It is the type site of Dalma culture, a prehistoric culture of north-western Iran from the fifth millennium B.C.

Hacınebi Tepe is an ancient Near East archaeological site 3.5 kilometers north of the modern town of Birecik and near the Euphrates river crossing between Apamea and Zeugma in Şanlıurfa Province, Turkey. The area marks the northernmost easily navigable route of the Euphrates River. The site was occupied in the 4th millennium BC by a local population, joined by an enclave of the Uruk culture in the middle of that millennium. It was then abandoned aside from occasional use for burials, until the Hellenistic period when it was again fully occupied. The sites final use was as a Roman farmstead.