The Ubaid period is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially in 1919 by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.

Tell Brak was an ancient city in Syria; its remains constitute a tell located in the Upper Khabur region, near the modern village of Tell Brak, 50 kilometers north-east of Al-Hasaka city, Al-Hasakah Governorate. The city's original name is unknown. During the second half of the third millennium BC, the city was known as Nagar and later on, Nawar.

Chagar Bazar is a tell, or settlement mound, in northern Al-Hasakah Governorate, Syria. It is a short distance from the major ancient city of Nagar. The site was occupied from the Halaf period until the middle of the 2nd millennium BC.

Tell Fekheriye is an ancient site in the Khabur river basin in al-Hasakah Governorate of northern Syria. It is securely identified as the site of Sikkan, attested since c. 2000 BC. While under an Assyrian governor c. 1000 BC it was called Sikani. Sikkan was part of the Syro-Hittite state of Bit Bahiani in the early 1st millennium BC. In the area, several mounds, called tells, can be found in close proximity: Tell Fekheriye, Ras al-Ayn, and 2.5 kilometers east of Tell Halaf, site of the Aramean and Neo-Assyrian city of Guzana. During the excavation, the Tell Fekheriye bilingual inscription was discovered at the site, which provides the source of information about Hadad-yith'i.

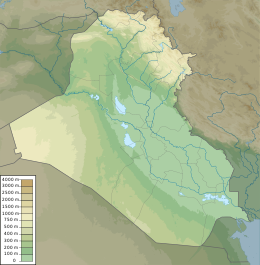

The history of Mesopotamia ranges from the earliest human occupation in the Paleolithic period up to Late antiquity. This history is pieced together from evidence retrieved from archaeological excavations and, after the introduction of writing in the late 4th millennium BC, an increasing amount of historical sources. While in the Paleolithic and early Neolithic periods only parts of Upper Mesopotamia were occupied, the southern alluvium was settled during the late Neolithic period. Mesopotamia has been home to many of the oldest major civilizations, entering history from the Early Bronze Age, for which reason it is often called a cradle of civilization.

Tepe Gawra is an ancient Mesopotamian settlement 15 miles NNE of Mosul in northwest Iraq that was occupied between 5000 and 1500 BC. It is roughly a mile from the site of Nineveh and 2 miles E of the site of Khorsabad. It contains remains from the Halaf period, the Ubaid period, and the Uruk period. Tepe Gawra contains material relating to the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period c. 5,500–5,000 BC.

In the archaeology of Southwest Asia, the Late Neolithic, also known as the Ceramic Neolithic or Pottery Neolithic, is the final part of the Neolithic period, following on from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic and preceding the Chalcolithic. It is sometimes further divided into Pottery Neolithic A (PNA) and Pottery Neolithic B (PNB) phases.

The Samarra culture is a Late Neolithic archaeological culture of northern Mesopotamia, roughly dated to between 5500 and 4800 BCE. It partially overlaps with Hassuna and early Ubaid. Samarran material culture was first recognized during excavations by German Archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld at the site of Samarra. Other sites where Samarran material has been found include Tell Shemshara, Tell es-Sawwan, and Yarim Tepe.

Tell Arpachiyah is a prehistoric archaeological site in Nineveh Province (Iraq). It takes its name from a more recent village located about 4 miles (6.4 km) from Nineveh. The local name of the mound on which the site is located is Tepe Reshwa.

Tell Mashnaqa is an archaeological site located on the Khabur River, a tributary to the Euphrates, about 30 kilometres (19 mi) south of Al-Hasakah in northeastern Syria. The earliest occupation of the site dates to the Ubaid period, and was excavated by a Danish team from 1990–1995 in four seasons.

Khabur ware is a specific type of pottery named after the Khabur River region, in northeastern Syria, where large quantities of it were found by the archaeologist Max Mallowan at the site of Chagar Bazar. The pottery's distribution is not confined to the Khabur region, but spreads across northern Iraq and is also found at a few sites in Turkey and Iran.

Tell Sabi Abyad is an archaeological site in the Balikh River valley in northern Syria. It lies about 2 kilometers south of Tell Hammam et-Turkman.The site consists of four prehistoric mounds that are numbered Tell Sabi Abyad I to IV. Extensive excavations showed that these sites were inhabited already around 7500 to 5500 BC, although not always at the same time; the settlement shifted back and forth among these four sites.

Tell Halula is a large, prehistoric, neolithic tell, about 8 hectares (860,000 sq ft) in size, located around 105 kilometres (65 mi) east of Aleppo and 25 kilometres (16 mi) northwest of Manbij in the Raqqa Governorate of Syria.

Ilī-padâ or Ili-iḫaddâ, the reading of the name (m)DINGIR.PA.DA being uncertain, was a member of a side-branch of the Assyrian royal family who served as grand vizier, or sukkallu rabi’u, of Assyria, and also as king, or šar, of the dependent state of Ḫanigalbat around 1200 BC. He was a contemporary of the Assyrian king Aššur-nīrāri III, c. 1203–1198 BC.

Peter M. M. G. Akkermans is a Dutch archaeologist and Professor of Ancient Near Eastern archaeology at Leiden University.

The Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period or HUT is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. It lies chronologically between the Halaf period and the Ubaid period. It is still a complex and rather poorly understood period. At the same time, recent efforts were made to study the gradual change from Halaf style pottery to Ubaid style pottery in various parts of North Mesopotamia.

Yarim Tepe is an archaeological site of an early farming settlement that goes back to about 6000 BC. It is located in the Sinjar valley some 7km southwest from the town of Tal Afar in northern Iraq. The site consists of several hills reflecting the development of the Hassuna culture, and then of the Halaf and Ubaid cultures.

The prehistory of Mesopotamia is the period between the Paleolithic and the emergence of writing in the area of the Fertile Crescent around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, as well as surrounding areas such as the Zagros foothills, southeastern Anatolia, and northwestern Syria.

Tell Hammam et-Turkman is an ancient Near Eastern tell site located in the Balikh River valley in Raqqa Governorate, northern Syria, not far from the Tell Sabi Abyad site and around 80 km north of the city of Raqqa. The Tell is located on the left bank of the Balikh and has a diameter of 500 m and is 45 m high. 500 m north is the modern village of Damešliyye.