Mehrgarh is a Neolithic archaeological site situated on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan in Pakistan. It is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River and between the modern-day Pakistani cities of Quetta, Kalat and Sibi. The site was discovered in 1974 by the French Archaeological Mission led by the French archaeologists Jean-François Jarrige and Catherine Jarrige. Mehrgarh was excavated continuously between 1974 and 1986, and again from 1997 to 2000. Archaeological material has been found in six mounds, and about 32,000 artifacts have been collected from the site. The earliest settlement at Mehrgarh, located in the northeast corner of the 495-acre (2.00 km2) site, was a small farming village dated between 7000 BCE and 5500 BCE.

The Neolithic or New Stone Age is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Europe, Asia, Mesopotamia and Africa. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts of the world. This "Neolithic package" included the introduction of farming, domestication of animals, and change from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to one of settlement. The term 'Neolithic' was coined by Sir John Lubbock in 1865 as a refinement of the three-age system.

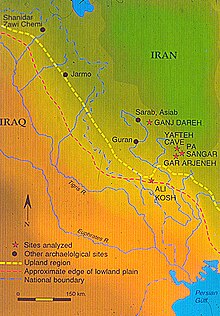

The Zagros Mountains are a mountain range in Iran, northern Iraq, and southeastern Turkey. The mountain range has a total length of 1,600 km. The Zagros range begins in northwestern Iran and roughly follows Iran's western border while covering much of southeastern Turkey and northeastern Iraq. From this border region, the range continues southeast to the waters of the Persian Gulf. It spans the southern parts of the Armenian highlands, and the whole length of the western and southwestern Iranian plateau, ending at the Strait of Hormuz. The highest point is Mount Dena, at 4,409 metres (14,465 ft).

Göbekli Tepe is a Neolithic archaeological site in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey. The settlement was inhabited from around 9500 BCE to at least 8000 BCE, during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic. It is famous for its large circular structures that contain massive stone pillars – among the world's oldest known megaliths. Many of these pillars are decorated with anthropomorphic details, clothing, and sculptural reliefs of wild animals, providing archaeologists rare insights into prehistoric religion and the particular iconography of the period. The 15 m (50 ft) high, 8 ha (20-acre) tell is densely covered with ancient domestic structures and other small buildings, quarries, and stone-cut cisterns from the Neolithic, as well as some traces of activity from later periods.

The Neolithic Revolution, also known as the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period in Afro-Eurasia from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an increasingly large population possible. These settled communities permitted humans to observe and experiment with plants, learning how they grew and developed. This new knowledge led to the domestication of plants into crops.

The Dawenkou culture was a Chinese Neolithic culture primarily located in the eastern province of Shandong, but also appearing in Anhui, Henan and Jiangsu. The culture existed from 4300 to 2600 BC, and co-existed with the Yangshao culture. Turquoise, jade and ivory artefacts are commonly found at Dawenkou sites. The earliest examples of alligator drums appear at Dawenkou sites. Neolithic signs, perhaps related to subsequent scripts, such as those of the Shang dynasty, have been found on Dawenkou pottery. Additionally, the Dawenkou practiced dental ablation and cranial deformation, practices that disappeared in China by the Chinese Bronze Age.

Tepe Sialk is a large ancient archeological site in a suburb of the city of Kashan, Isfahan Province, in central Iran, close to Fin Garden. The culture that inhabited this area has been linked to the Zayandeh River Culture.

Ganj Dareh is a Neolithic settlement in western Iran. It is located in the Harsin County in east of Kermanshah Province, in the central Zagros Mountains.

Kent Vaughn Flannery is a North American archaeologist who has conducted and published extensive research on the pre-Columbian cultures and civilizations of Mesoamerica, and in particular those of central and southern Mexico. He has also published influential work on origins of agriculture and village life in the Near east, pastoralists in the Andes, and cultural evolution, and many critiques of modern trends in archaeological method, theory, and practice. At the University of Chicago he gained his B.A. degree in 1954; the M.A. in 1961 and a Ph.D. in 1964. From 1966 to 1980 he directed project “Prehistory and Human Ecology of the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico.” dealing with the origins of agriculture, village life, and social inequality in Mexico. He is James B. Griffin Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Michigan. In 2005, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.

The history of Indian cuisine consists of cuisine of the Indian subcontinent, which is rich and diverse. The diverse climate in the region, ranging from deep tropical to alpine, has also helped considerably broaden the set of ingredients readily available to the many schools of cookery in India. In many cases, food has become a marker of religious and social identity, with varying taboos and preferences which has also driven these groups to innovate extensively with the food sources that are deemed acceptable.

The oldest evidence for Indian agriculture is in north-west India at the site of Mehrgarh, dated ca. 7000 BCE, with traces of the cultivation of plants and domestication of crops and animals. Indian subcontinent agriculture was the largest producer of wheat and grain. They settled life soon followed with implements and techniques being developed for agriculture. Double monsoons led to two harvests being reaped in one year. Indian products soon reached the world via existing trading networks and foreign crops were introduced to India. Plants and animals—considered essential to their survival by the Indians—came to be worshiped and venerated.

Choghā Mīsh (Persian language; چغامیش čoġā mīš) dating back to about 6800 BC, is the site of a Chalcolithic settlement located in the Khuzistan Province Iran on the eastern Susiana Plain. It was occupied at the beginning of 6800 BC and continuously from the Neolithic up to the Proto-Literate period, thus spanning the time periods from Archaic through Proto-Elamite period. After the decline of the site about 4400 BC, the nearby Susa, on the western Susiana Plain, became culturally dominant in this area. Chogha Mish is located just to the east of Dez River, and about 25 kilometers to the east from the ancient Susa. The similar, though much smaller site of Chogha Bonut lies six kilometers to the west.

Chogha Bonut is an archaeological site in south-western Iran, located in the Khuzistan Province.

Tell Halula is a large, prehistoric, neolithic tell, about 8 hectares (860,000 sq ft) in size, located around 105 kilometres (65 mi) east of Aleppo and 25 kilometres (16 mi) northwest of Manbij in the Raqqa Governorate of Syria.

The prehistory of the Iranian plateau, and the wider region now known as Greater Iran, as part of the prehistory of the Near East is conventionally divided into the Paleolithic, Epipaleolithic, Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age periods, spanning the time from the first settlement by archaic humans about a million years ago until the beginning of the historical record during the Neo-Assyrian Empire, in the 8th century BC.

The Kelteminar culture was a Neolithic archaeological culture of sedentary fishermen occupying the semi-desert and desert areas of the Karakum and Kyzyl Kum deserts and the deltas of the Amu Darya and Zeravshan rivers in the territories of ancient Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

Frank Hole is an American Near Eastern archaeologist known for his work on the prehistory of Iran, the origins of food production, and the archaeology of pastoral nomadism. He is C. J. MacCurdy Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Yale University.

Sang-i Chakmak is a Neolithic archaeological site located about 1 km (0.62 mi) north of the village of Bastam in the northern Semnan Province of Iran, on the southeastern flank of the Elburs Mountains. The site represents quite well the transition from the aceramic Neolithic phase in the general area; this was taking place during the 7th millennium BC.

Indus–Mesopotamia relations are thought to have developed during the second half of 3rd millennium BCE, until they came to a halt with the extinction of the Indus valley civilization after around 1900 BCE. Mesopotamia had already been an intermediary in the trade of lapis lazuli between the Indian subcontinent and Egypt since at least about 3200 BCE, in the context of Egypt-Mesopotamia relations.

The site of Chogha Gavaneh, on two major routes, one between south and central Mesopotamia and Iran and the other between northern Mesopotamia and the Susa are, lies within the modern city of Eslamabad-e Gharb in Kermanshah Province in Iran and about 60 kilometers west of modern Kermanshah. It was occupied from the Early Neolithic Period to Middle Bronze Age and, after a time of abandonment, in the Islamic period.