The Dravidian languages are a family of languages spoken by 250 million people, mainly in South India, north-east Sri Lanka, and south-west Pakistan, with pockets elsewhere in South Asia.

Akkadian is an extinct East Semitic language that was spoken in ancient Mesopotamia from the third millennium BC until its gradual replacement in common use by Old Aramaic among Assyrians and Babylonians from the 8th century BC.

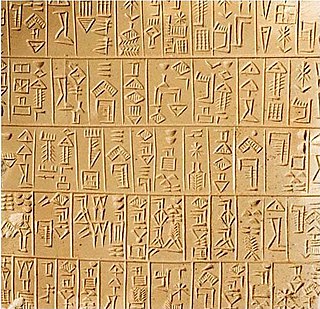

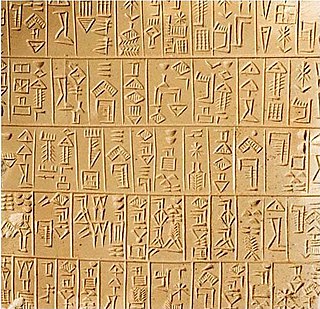

Sumerian was the language of ancient Sumer. It is one of the oldest attested languages, dating back to at least 2900 BC. It is a local language isolate that was spoken in ancient Mesopotamia, in the area that is modern-day Iraq.

In linguistics and etymology, suppletion is traditionally understood as the use of one word as the inflected form of another word when the two words are not cognate. For those learning a language, suppletive forms will be seen as "irregular" or even "highly irregular". For example, go:went is a suppletive paradigm, because go and went are not etymologically related, whereas mouse:mice is irregular but not suppletive, since the two words come from the same Old English ancestor.

Elam was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretching from the lowlands of what is now Khuzestan and Ilam Province as well as a small part of southern Iraq. The modern name Elam stems from the Sumerian transliteration elam(a), along with the later Akkadian elamtu, and the Elamite haltamti. Elamite states were among the leading political forces of the Ancient Near East. In classical literature, Elam was also known as Susiana, a name derived from its capital Susa.

The Elamo-Dravidian language family is a hypothesised language family that links the Elamite language of ancient Elam to the Dravidian languages of South Asia. The latest version (2015) of the hypothesis entails a reclassification of Brahui as being more closely related to Elamite than to the remaining Dravidian languages. Linguist David McAlpin has been a chief proponent of the Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis, followed by Franklin Southworth as the other major supporter. The hypothesis has gained attention in academic circles, but has been subject to serious criticism by linguists, and remains only one of several possible scenarios for the origins of the Dravidian languages. Elamite is generally accepted by scholars to be a language isolate, unrelated to any other known language.

Hurrian is an extinct Hurro-Urartian language spoken by the Hurrians (Khurrites), a people who entered northern Mesopotamia around 2300 BC and had mostly vanished by 1000 BC. Hurrian was the language of the Mitanni kingdom in northern Mesopotamia and was likely spoken at least initially in Hurrian settlements in modern-day Syria.

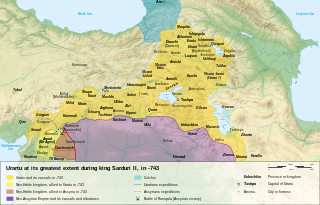

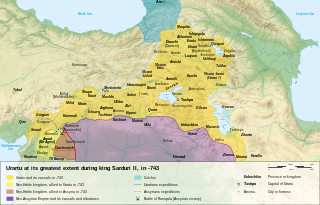

Urartian or Vannic is an extinct Hurro-Urartian language which was spoken by the inhabitants of the ancient kingdom of Urartu, which was centered on the region around Lake Van and had its capital, Tushpa, near the site of the modern town of Van in the Armenian highlands, now in the Eastern Anatolia region of Turkey. Its past prevalence is unknown. While some believe it was probably dominant around Lake Van and in the areas along the upper Zab valley, others believe it was spoken by a relatively small population who comprised a ruling class.

Alyutor or Alutor is a language of Russia that belongs to the Chukotkan branch of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages, by the Alyutors. It is moribund, as only 25 speakers were reported in the 2010 Russian census.

Bengali grammar is the study of the morphology and syntax of Bengali, an Indo-European language spoken in the Indian subcontinent. Given that Bengali has two forms, Bengali: চলিত ভাষা and Bengali: সাধু ভাষা, it is important to note that the grammar discussed below applies fully only to the Bengali: চলিত (cholito) form. Shadhu bhasha is generally considered outdated and no longer used either in writing or in normal conversation. Although Bengali is typically written in the Bengali script, a romanization scheme is also used here to suggest the pronunciation.

The Nafsan language, also known as South Efate or Erakor, is a Southern Oceanic language spoken on the island of Efate in central Vanuatu. As of 2005, there are approximately 6,000 speakers who live in coastal villages from Pango to Eton. The language's grammar has been studied by Nick Thieberger, who has produced a book of stories and a dictionary of the language.

Linear Elamite was a writing system used in Elam during the Bronze Age between c. 2300 and 1850 BCE, and known mainly from a few extant monumental inscriptions. It was used contemporaneously with Elamite cuneiform and records the Elamite language. The French archaeologist François Desset and his colleagues have argued that it is the oldest known purely phonographic writing system, although others, such as the linguist Michael Mäder, have argued that it is partly logographic.

The Persepolis Administrative Archive are two groups of clay administrative archives — sets of records physically stored together – found in Persepolis dating to the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The discovery was made during legal excavations conducted by the archaeologists from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago in the 1930s. Hence they are named for their in situ findspot: Persepolis. The archaeological excavations at Persepolis for the Oriental Institute were initially directed by Ernst Herzfeld from 1931 to 1934 and carried on from 1934 until 1939 by Erich Schmidt.

Sanskrit has inherited from its parent, the Proto-Indo-European language, an elaborate system of verbal morphology, much of which has been preserved in Sanskrit as a whole, unlike in other kindred languages, such as Ancient Greek or Latin. Sanskrit verbs thus have an inflection system for different combinations of tense, aspect, mood, voice, number, and person. Non-finite forms such as participles are also extensively used.

Matthew Wolfgang Stolper is Professor of Assyriology and the John A. Wilson Professor of Oriental Studies in the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago. He received a B.A. from Harvard in 1965, an M.A. from the University of Michigan in 1967, and a Ph.D. from the University of Michigan in 1974.

In linguistic morphology, inflection is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, voice, aspect, person, number, gender, mood, animacy, and definiteness. The inflection of verbs is called conjugation, while the inflection of nouns, adjectives, adverbs, etc. can be called declension.

Old Norse has three categories of verbs and two categories of nouns. Conjugation and declension are carried out by a mix of inflection and two nonconcatenative morphological processes: umlaut, a backness-based alteration to the root vowel; and ablaut, a replacement of the root vowel, in verbs.

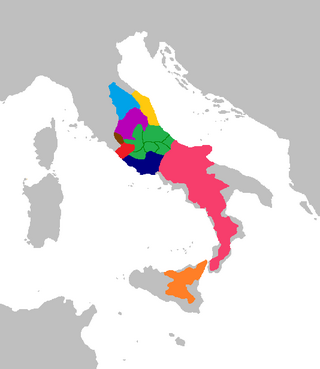

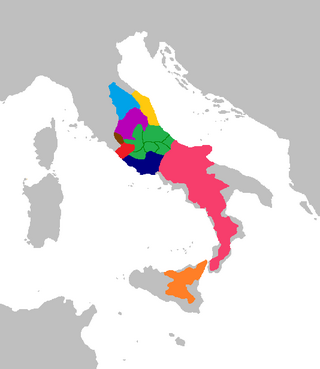

The Proto-Italic language is the ancestor of the Italic languages, most notably Latin and its descendants, the Romance languages. It is not directly attested in writing, but has been reconstructed to some degree through the comparative method. Proto-Italic descended from the earlier Proto-Indo-European language.

The Shutrukid dynasty was a dynasty of the Elamite empire, in modern Iran. Under the Shutrukids, Elam reached a height in power.

David Wayne McAlpin was an American linguist who specialized in Elamitic and Dravidian languages. Born in West Frankfort, Illinois, he received his Bachelor’s degree in linguistics at the University of Chicago, studying under A. K. Ramanujan. Following this, he received his Ph.D. in linguistics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and an M.B.A. from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. He is best known for his work attempting to demonstrate a genetic relationship between Elamite language and the Dravidian languages.