The Tuscarora are an Indigenous People of the Northeastern Woodlands in Canada and the United States. They are an Iroquoian Native American and First Nations people. The Tuscarora Nation, a federally recognized tribe, is based in New York, and the Tuscarora First Nation is one of the Six Nations of the Grand River in Ontario.

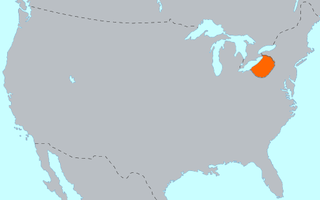

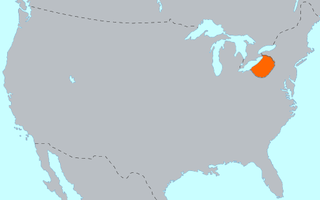

The Wyandot people are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of the present-day United States and Canada. Their Wyandot language belongs to the Iroquoian language family.

The Beaver Wars, also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars, were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout the Saint Lawrence River valley in Canada and the Great Lakes region which pitted the Iroquois against the Hurons, northern Algonquians and their French allies. As a result of this conflict, the Iroquois destroyed several confederacies and tribes through warfare: the Hurons or Wendat, Erie, Neutral, Wenro, Petun, Susquehannock, Mohican and northern Algonquins whom they defeated and dispersed, some fleeing to neighbouring peoples and others assimilated, routed, or killed.

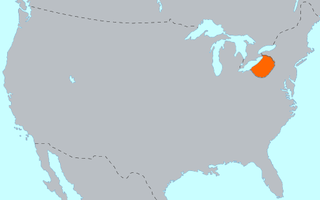

The Neutral Confederacy was a tribal confederation of Iroquoian peoples. Its heartland was in the floodplain of the Grand River in what is now Ontario, Canada. At its height, its wider territory extended toward the shores of lakes Erie, Huron, and Ontario, as well as the Niagara River in the east. To the northeast were the neighbouring territories of Huronia and the Petun Country, which were inhabited by other Iroquoian confederacies from which the term Neutrals Attawandaron was derived. The five-nation Iroquois Confederacy was across Lake Ontario to the southeast.

Tuscarora, sometimes called Skarò˙rə̨ˀ, is the Iroquoian language of the Tuscarora people, spoken in southern Ontario, Canada, North Carolina and northwestern New York around Niagara Falls, in the United States before becoming extinct in late 2020. The historic homeland of the Tuscarora was in eastern North Carolina, in and around the Goldsboro, Kinston, and Smithfield areas.

The Erie people were an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands historically living on the south shore of Lake Erie. An Iroquoian-speaking tribe, they lived in what is now western New York, northwestern Pennsylvania, and northern Ohio before 1658. Their nation was almost exterminated in the mid-17th century by five years of prolonged warfare with the powerful neighboring Iroquois for helping the Huron in the Beaver Wars for control of the fur trade. Captured survivors were adopted or enslaved by the Iroquois.

The Meherrin people are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who spoke an Iroquian language. They lived between the Piedmont and coastal plains at the border of Virginia and North Carolina.

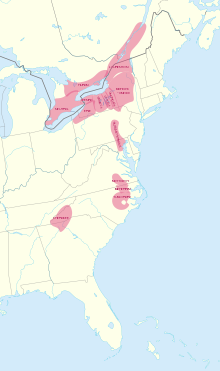

Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands include Native American tribes and First Nation bands residing in or originating from a cultural area encompassing the northeastern and Midwest United States and southeastern Canada. It is part of a broader grouping known as the Eastern Woodlands. The Northeastern Woodlands is divided into three major areas: the Coastal, Saint Lawrence Lowlands, and Great Lakes-Riverine zones.

Susquehannock, also known as Conestoga, is an extinct Iroquoian language spoken by the Native American people variously known as the Susquehannock or Conestoga.

Laurentian, or St. Lawrence Iroquoian, was an Iroquoian language spoken until the late 16th century along the shores of the Saint Lawrence River in present-day Quebec and Ontario, Canada. It is believed to have disappeared with the extinction of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, likely as a result of warfare by the more powerful Mohawk from the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy to the south, in present-day New York state of the United States.

The St. Lawrence Iroquoians were an Iroquoian Indigenous people who existed until about the late 16th century. They concentrated along the shores of the St. Lawrence River in present-day Quebec and Ontario, Canada, and in the American states of New York and northernmost Vermont. They spoke Laurentian languages, a branch of the Iroquoian family.

The Nottoway are an Iroquoian Native American tribe in Virginia. The Nottoway spoke a Nottoway language in the Iroquoian language family.

The Petun, also known as the Tobacco people or Tionontati, were an indigenous Iroquoian people of the woodlands of eastern North America. Their last known traditional homeland was south of Lake Huron's Georgian Bay, in what is today's Canadian province of Ontario.

The Wenrohronon or Wenro people were an Iroquoian indigenous nation of North America, originally residing in present-day western New York, who were conquered by the Confederation of the Five Nations of the Iroquois in two decisive wars between 1638–1639 and 1643. This was likely part of the Iroquois Confederacy campaign against the Neutral people, another Iroquoian-speaking tribe, which lived across the Niagara River. This warfare was part of what was known as the Beaver Wars, as the Iroquois worked to dominate the lucrative fur trade. They used winter attacks, which were not usual among Native Americans, and their campaigns resulted in attrition of both the larger Iroquoian confederacies, as they had against the numerous Huron.

The protohistoric period of the state of West Virginia in the United States began in the mid-sixteenth century with the arrival of European trade goods. Explorers and colonists brought these goods to the eastern and southern coasts of North America and were brought inland by native trade routes. This was a period characterized by increased intertribal strife, rapid population decline, the abandonment of traditional life styles, and the extinction and migrations of many Native American groups.

Proto-Iroquoian is the theoretical proto-language of the Iroquoian languages. Lounsbury (1961) estimated from glottochronology a time depth of 3,500 to 3,800 years for the split of North and South Iroquoian.

Nottoway, also called Cheroenhaka, is an extinct language spoken by the Nottoway people. Nottoway is closely related to Tuscarora within the Iroquoian language family. Two tribes of Nottoway are recognized by the state of Virginia: the Nottoway Indian Tribe of Virginia and the Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Indian Tribe. Other Nottoway descendants live in Wisconsin and Canada, where some of their ancestors fled in the 18th century. The last known speaker, Edith Turner, died in 1838. The Nottoway people are undertaking work for language revival.

Erie is an extinct language, believed to have been Iroquoian, similar to Wyandot, formerly spoken by the Erie people. It was poorly documented, and linguists are not certain that this conclusion is correct. There have been few connections with Europeans and the Erie's with the French, and Dutch being peaceful, while the English being mostly hostile.

Neutral or Neutral Huron was the Iroquoian language spoken by the Neutral Nation.