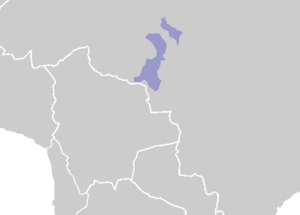

The Chapacuran languages are a nearly extinct Native American language family of South America. Almost all Chapacuran languages are extinct, and the four that are extant are moribund. They are spoken in Rondônia in the southern Amazon Basin of Brazil and in northern Bolivia.

Barbacoan is a language family spoken in Colombia and Ecuador.

Arawan is a family of languages spoken in western Brazil and Peru (Ucayali).

Macro-Jê is a medium-sized language family in South America, mostly in Brazil but also in the Chiquitanía region in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, as well as (formerly) in small parts of Argentina and Paraguay. It is centered on the Jê language family, with most other branches currently being single languages due to recent extinctions.

The Borôroan languages of Brazil are Borôro and the extinct Umotína and Otuke. They are sometimes considered to form part of the proposed Macro-Jê language family, though this has been disputed.

The Nambikwara is an indigenous people of Brazil, living in the Amazon. Currently about 1,200 Nambikwara live in indigenous territories in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso along the Guaporé and Juruena rivers. Their villages are accessible from the Pan-American highway.

Tacanan is a family of languages spoken in Bolivia, with Ese’ejja also spoken in Peru. It may be related to the Panoan languages. Many of the languages are endangered.

The Waorani (Huaorani) language, commonly known as Sabela is a vulnerable language isolate spoken by the Huaorani people, an indigenous group living in the Amazon rainforest between the Napo and Curaray Rivers in Ecuador. A small number of speakers with so-called uncontacted groups may live in Peru.

Yuracaré is an endangered language isolate of central Bolivia in Cochabamba and Beni departments spoken by the Yuracaré people.

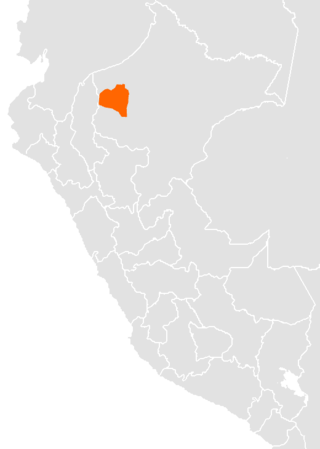

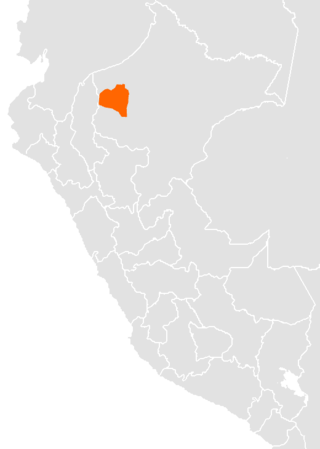

The Cahuapanan languages are a language family spoken in the Amazon basin of northern Peru. They include two languages, Chayahuita and Jebero, which are spoken by more than 11,300 people. Chayahuita is spoken by most of that number, but Jebero is almost extinct.

Candoshi-Shapra is an indigenous American language isolate, spoken by several thousand people in western South America along the Chapuli, Huitoyacu, Pastaza, and Morona river valleys. There are two dialects, Chapara and Kandoashi (Kandozi). It is an official language of Peru, like other native languages in the areas in which they are spoken and are the predominant language in use. Around 88.5 percent of the speakers are bilingual with Spanish. The literacy rate in Candoshi-Shapra is 10 to 30 percent and 15 to 25 percent in the second language Spanish. There is a Candoshi-Shapra dictionary, and grammar rules have been codified.

Nambikwara is an indigenous language spoken by the Nambikwara, who reside on federal reserves covering approximately 50,000 square kilometres of land in Mato Grosso and neighbouring parts of Rondonia in Brazil. Due to the fact that the Nambikwara language has such a high proportion of speakers, and the fact that the community has a positive attitude towards the language, it is not considered to be endangered despite the fact that its speakers constitute a small minority of the Brazilian population. For these reasons, UNESCO instead classifies Nambikwara as vulnerable.

Irántxe /iˈɻɑːntʃeɪ/, also known as Mỹky (Münkü) or still as Irántxe-Münkü, is an indigenous language spoken by the Irántxe and Mỹky peoples in the state of Mato Grosso in Brazil. Recent descriptions of the language analyze it as a language isolate, in that it "bears no similarity with other language families". Monserrat (2010) is a well-reviewed grammar of the language.

Aikanã is an endangered language isolate spoken by about 200 Aikanã people in Rondônia, Brazil. It is morphologically complex and has SOV word order. Aikanã uses the Latin script. The people live with speakers of Koaia (Kwaza).

Harakmbut or Harakmbet is the native language of the Harakmbut people of Peru. It is spoken along the Madre de Dios and Colorado Rivers, in the pre-contact country of the people. There are two dialects that remain vital: Amarakaeri (Arakmbut) and Watipaeri (Huachipaeri), which are reported to be mutually intelligible. The relationship between speakers of the two dialects is hostile.

The Kaingang language is a Southern Jê language spoken by the Kaingang people of southern Brazil. The Kaingang nation has about 30,000 people, and about 60–65% speak the language. Most also speak Portuguese.

Warao is the native language of the Warao people. A language isolate, it is spoken by about 33,000 people primarily in northern Venezuela, Guyana and Suriname. It is notable for its unusual object–subject–verb word order. The 2015 Venezuelan film Gone with the River was spoken in Warao.

Mamaindê, also known as Northern Nambikwara, is a Nambikwaran language spoken in the Mato Grosso state of Brazil, in the very north of the indigenous reserve, Terra Indígena Vale do Guaporé, between the Pardo and Cabixi Rivers. In the southern part of the reserve, speakers of Sabanê and Southern Nambikwara are found.

The Ofayé or Opaye language, also Ofaié-Xavante, Opaié-Shavante, forms its own branch of the Macro-Jê languages. It is spoken by only a couple of the small Ofayé people, though language revitalization efforts are underway. Grammatical descriptions have been made by the Pankararú linguist Maria das Dores de Oliveira (Pankararu), as well as by Sarah C. Gudschinsky and Jennifer E. da Silva, from the Universidade Federal do Mato Grosso do Sul.

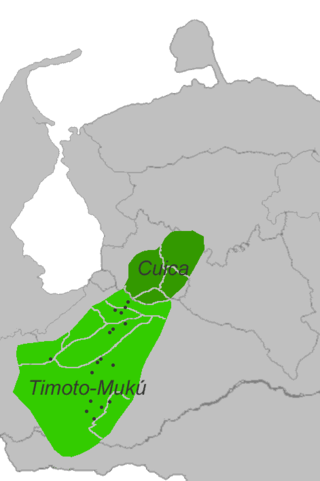

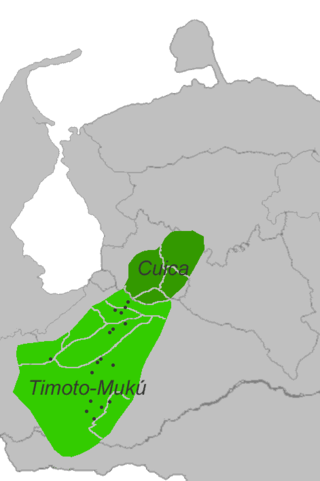

The Timotean languages were spoken in the Venezuelan Andes around what is now Mérida. It is assumed that they are extinct. However, Timote may survive in the so-far unattested Mutú (Loco) language, as this occupies a mountain village (Mutús) within the old Timote state.