The Behistun Inscription is a multilingual Achaemenid royal inscription and large rock relief on a cliff at Mount Behistun in the Kermanshah Province of Iran, near the city of Kermanshah in western Iran, established by Darius the Great. It was important to the decipherment of cuneiform, as it is the longest known trilingual cuneiform inscription, written in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian.

Persepolis was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire. It is situated in the plains of Marvdasht, encircled by southern Zagros mountains, Fars province of Iran. It is one of the key Iranian Cultural heritages. UNESCO declared the ruins of Persepolis a World Heritage Site in 1979.

Elam was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretching from the lowlands of what is now Khuzestan and Ilam Province as well as a small part of southern Iraq. The modern name Elam stems from the Sumerian transliteration elam(a), along with the later Akkadian elamtu, and the Elamite haltamti. Elamite states were among the leading political forces of the Ancient Near East. In classical literature, Elam was also known as Susiana, a name derived from its capital Susa.

Old Persian is one of two directly attested Old Iranian languages and is the ancestor of Middle Persian. Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native speakers as ariya (Iranian). Old Persian is close to both Avestan and the language of the Rig Veda, the oldest form of the Sanskrit language. All three languages are highly inflected.

Elamite, also known as Hatamtite and formerly as Susian, is an extinct language that was spoken by the ancient Elamites. It was recorded in what is now southwestern Iran from 2600 BC to 330 BC. Elamite works disappear from the archeological record after Alexander the Great entered Iran, but the spoken language might have survived until the 11th century AD. Elamite is generally thought to have no demonstrable relatives and is usually considered a language isolate. The lack of established relatives makes its interpretation difficult.

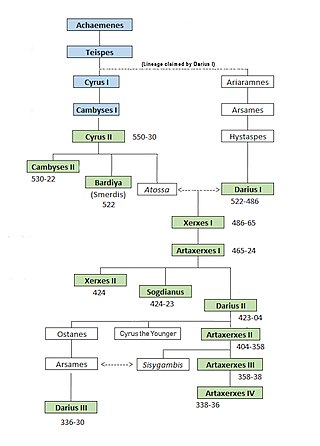

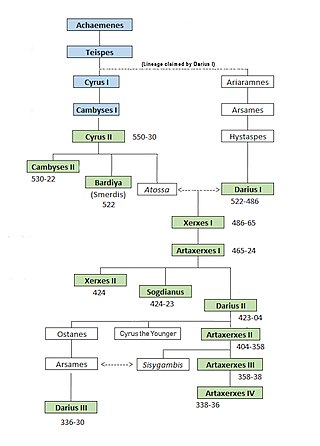

Achaemenes was the progenitor of the Achaemenid dynasty of rulers of Persia.

Persian columns or Persepolitan columns are the distinctive form of column developed in the Achaemenid architecture of ancient Persia, probably beginning shortly before 500 BCE. They are mainly known from Persepolis, where the massive main columns have a base, fluted shaft, and a double-animal capital, most with bulls. Achaemenid palaces had enormous hypostyle halls called apadana, which were supported inside by several rows of columns. The Throne Hall or "Hall of a Hundred Columns" at Persepolis, measuring 70 × 70 metres was built by the Achaemenid king Artaxerxes I. The apadana hall is even larger. These often included a throne for the king and were used for grand ceremonial assemblies; the largest at Persepolis and Susa could fit ten thousand people at a time.

Georg Friedrich Grotefend was a German epigraphist and philologist. He is known mostly for his contributions toward the decipherment of cuneiform.

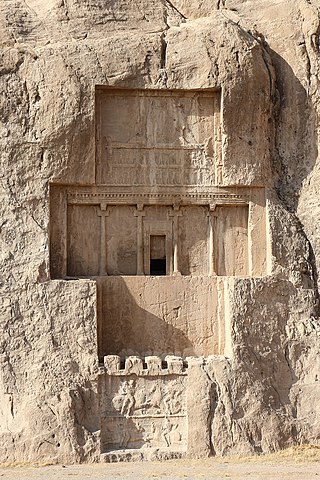

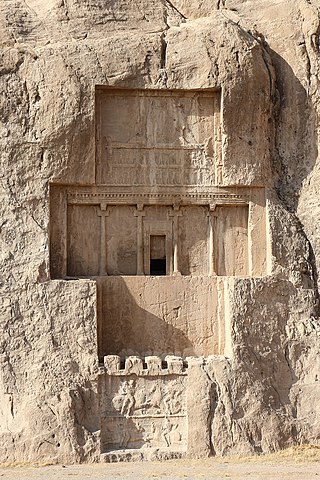

Naqsh-e Rostam is an ancient archeological site and necropolis located about 13 km northwest of Persepolis, in Fars Province, Iran. A collection of ancient Iranian rock reliefs are cut into the face of the mountain and the mountain contains the final resting place of four Achaemenid kings, notably king Darius the Great and his son, Xerxes. This site is of great significance to the history of Iran and to Iranians, as it contains various archeological sites carved into the rock wall through time for more than a millennium from the Elamites and Achaemenids to Sassanians. It lies a few hundred meters from Naqsh-e Rajab, with a further four Sassanid rock reliefs, three celebrating kings and one a high priest.

Teïspes ruled Anshan in 675–640 BC. He was the son of Achaemenes of Persis and an ancestor of Cyrus the Great. There is evidence that Cyrus I and Ariaramnes were both his sons. Cyrus I is the grandfather of Cyrus the Great, whereas Ariaramnes is the great-grandfather of Darius the Great.

Linear Elamite was a writing system used in Elam during the Bronze Age between c. 2300 and 1850 BCE, and known mainly from a few extant monumental inscriptions. It was used contemporaneously with Elamite cuneiform and records the Elamite language. The French archaeologist François Desset and his colleagues have argued that it is the oldest known purely phonographic writing system, although others, such as the linguist Michael Mäder, have argued that it is partly logographic.

Old Persian cuneiform is a semi-alphabetic cuneiform script that was the primary script for Old Persian. Texts written in this cuneiform have been found in Iran, Armenia, Romania (Gherla), Turkey, and along the Suez Canal. They were mostly inscriptions from the time period of Darius I, such as the DNa inscription, as well as his son, Xerxes I. Later kings down to Artaxerxes III used more recent forms of the language classified as "pre-Middle Persian".

The Persepolis Fortification Archive and Persepolis Treasury Archive are two groups of clay administrative archives — sets of records physically stored together – found in Persepolis dating to the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The discovery was made during legal excavations conducted by the archaeologists from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago in the 1930s. Hence they are named for their in situ findspot: Persepolis. The archaeological excavations at Persepolis for the Oriental Institute were initially directed by Ernst Herzfeld from 1931 to 1934 and carried on from 1934 until 1939 by Erich Schmidt.

Tushpa was the 9th-century BC capital of Urartu, later becoming known as Van which is derived from Biainili, the native name of Urartu. The ancient ruins are located just west of Van and east of Lake Van in the Van Province of Turkey. In 2016 it was inscribed in the Tentative list of World Heritage Sites in Turkey.

Achaemenid architecture includes all architectural achievements of the Achaemenid Persians manifesting in construction of spectacular cities used for governance and inhabitation, temples made for worship and social gatherings, and mausoleums erected in honor of fallen kings. Achaemenid architecture was influenced by Mesopotamian, Assyrian, Egyptian, Elamite, Lydian, Greek and Median architecture. The quintessential feature of Persian architecture was its eclectic nature with foreign elements, yet producing a unique Persian identity seen in the finished product. Achaemenid architecture is academically classified under Persian architecture in terms of its style and design.

Kul-e Farah is an archaeological site and open-air sanctuary situated in the Zagros mountain valley of Izeh/Mālamir, in south-western Iran, around 800 meters over sea level. Six Elamite rock reliefs are located in a small gorge marked by a seasonal creek bed on the plain's east side of the valley, near the town of Izeh in Khuzestan.

The tomb of Darius the Great (or Darius I) is one of the four tombs for Achaemenid kings at the historical site of Naqsh-e Rostam, located about 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) northwest of Persepolis in Iran. They are all situated at a considerable height above ground-level.

Heidemarie Koch was a German Iranologist.

The Caylus vase is an Egyptian alabaster jar dedicated in the name of the Achaemenid king Xerxes I in Egyptian hieroglyphs and Old Persian cuneiform, which in 1823 played an important role in the modern decipherment of cuneiform and the decipherment of ancient Egyptian scripts.

The decipherment of cuneiform began with the decipherment of Old Persian cuneiform between 1802 and 1836.