Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in Iran face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Sexual activity between members of the same sex is illegal and can be punishable by death, and people can legally change their assigned sex only through sex reassignment surgery. Currently, Iran is the only country confirmed to execute gay people, though death penalty for homosexuality might be enacted in Afghanistan.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in Saudi Arabia face repression and discrimination. The government of Saudi Arabia provides no legal protections for LGBT rights. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity is illegal within the country.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Afghan members of the LGBT community are forced to keep their gender identity and sexual orientation secret, in fear of violence and the death penalty. The religious nature of the country has limited any opportunity for public discussion, with any mention of homosexuality and related terms deemed taboo.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in Egypt face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. There are reports of widespread discrimination and violence towards openly LGBTQ people within Egypt, with police frequently prosecuting gay and transgender individuals.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people living in Lebanon face discrimination and legal difficulties not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Various courts have ruled that Article 534 of the Lebanese Penal Code, which prohibits having sexual relations that "contradict the laws of nature", should not be used to arrest LGBT people. Nonetheless, the law is still being used to harass and persecute LGBT people through occasional police arrests, in which detainees are sometimes subject to intrusive physical examinations.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Kazakhstan face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female kinds of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Kazakhstan, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in Bangladesh face widespread social and legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT people.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Malaysia face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Sodomy is a crime in the country, with laws enforced arbitrarily. Extrajudicial murders of LGBT people have also occurred in the country. There are no Malaysian laws that protect the LGBT community against discrimination and hate crimes. As such, the LGBT demographic in the country are hard to ascertain due to widespread fears from being ostracised and prosecuted, including violence.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people in Bhutan face legal challenges that are not faced by non-LGBTQ people. Bhutan does not provide any anti-discrimination laws for LGBT people, and same-sex unions are not recognised. However, same-sex sexual activity was decriminalised in Bhutan on 17 February 2021.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Somalia face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Consensual same-sex sexual activity is illegal for both men and women. In areas controlled by al-Shabab, and in Jubaland, capital punishment is imposed for such sexual activity. In other areas, where Sharia does not apply, the civil law code specifies prison sentences of up to three years as penalty. LGBT people are regularly prosecuted by the government and additionally face stigmatization among the broader population. Stigmatization and criminalisation of homosexuality in Somalia occur in a legal and cultural context where 99% of the population follow Islam as their religion, while the country has had an unstable government and has been subjected to a civil war for decades.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, non-binary and otherwise queer, non-cisgender, non-heterosexual citizens of El Salvador face considerable legal and social challenges not experienced by fellow heterosexual, cisgender Salvadorans. While same-sex sexual activity between all genders is legal in the country, same-sex marriage is not recognized; thus, same-sex couples—and households headed by same-sex couples—are not eligible for the same legal benefits provided to heterosexual married couples.

The initialism LGBTQ is used to refer collectively to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people and members of the specific group and to the community (subculture) that surrounds them. This can include rights advocates, artists, authors, etc.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Dominican Republic do not possess the same legal protections as non-LGBTQ residents, and face social challenges that are not experienced by other people. While the Dominican Criminal Code does not expressly prohibit same-sex sexual relations or cross-dressing, it also does not address discrimination or harassment on the account of sexual orientation or gender identity, nor does it recognize same-sex unions in any form, whether it be marriage or partnerships. Households headed by same-sex couples are also not eligible for any of the same rights given to opposite-sex married couples, as same-sex marriage is constitutionally banned in the country.

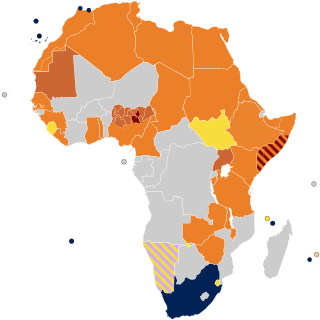

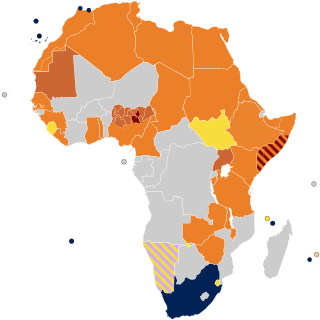

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Africa are generally poor in comparison to the Americas, Western Europe and Oceania.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights in Laos go unreported and unnoticed. While homosexuality is legal in Laos, it is very difficult to assess the current state of acceptance and violence that LGBTQ people face because of government interference. Numerous claims have suggested that Laos is one of the most tolerant communist states. Despite such claims, discrimination still exists. Laos provides no anti-discrimination protections for LGBT people, nor does it prohibit hate crimes based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for any of the rights that opposite-sex married couples enjoy, as neither same-sex marriage nor civil unions are legal.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBTQ) people in Liberia face legal and social challenges which others in the country do not experience. LGBT people in Liberia encounter widespread discrimination, including harassment, death threats, and at times physical attacks. Several prominent Liberian politicians and organizations have campaigned to restrict LGBT rights further, while several local, Liberian-based organizations exist to advocate and provide services for the LGBT community in Liberia. Same-sex sexual activity is criminalized regardless of the gender of those involved, with a maximum penalty of three years in prison, and same-sex marriage is illegal.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people generally have limited or highly restrictive rights in most parts of the Middle East, and are open to hostility in others. Sex between men is illegal in 9 of the 18 countries that make up the region. It is punishable by death in four of these 18 countries. The rights and freedoms of LGBT citizens are strongly influenced by the prevailing cultural traditions and religious mores of people living in the region – particularly Islam.

The following outline offers an overview and guide to LGBTQ topics:

Abdulrahman Akkad is a Syrian political blogger, public speaker and human rights activist. He currently resides in Berlin.