Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Niger face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Although same-sex sexual activity is legal, the Nigerien LGBT community faces stigmatization among the broader population.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Gabon face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Except for a period between July 2019 and June 2020, same-sex sexual activity has generally been legal in Gabon.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Burkina Faso face legal issues not experienced by non-LGBTQ citizens. Although same-sex sexual acts are legal for both men and women in Burkina Faso, there is no legal recognition of same-sex marriage or adoption rights.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Armenia face legal and social challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents, due in part to the lack of laws prohibiting discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity and in part to prevailing negative attitudes about LGBT persons throughout society.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Lithuania have evolved rapidly over the years, although LGBT people still face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female expressions of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Lithuania, but neither civil same-sex partnership nor same-sex marriages are available, meaning that there is no legal recognition of same-sex couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Moldova face legal and social challenges and discrimination not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same rights and benefits as households headed by opposite-sex couples. Same-sex unions are not recognized in the country, so consequently same-sex couples have little to no legal protection. Nevertheless, Moldova bans discrimination based on sexual orientation in the workplace, and same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 1995.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Kazakhstan face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female kinds of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Kazakhstan, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Tajikistan face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Tajikistan, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to heterosexual married couples.

Laws governing lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights are complex in Asia, and acceptance of LGBTQ persons is generally low. Same-sex sexual activity is outlawed in at least twenty Asian countries. In Afghanistan, Brunei, Iran, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen, homosexual activity results in death penalty. In addition, LGBT people also face extrajudicial executions from non-state actors such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant and Hamas in the Gaza Strip. While egalitarian relationships have become more frequent in recent years, they remain rare.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Guatemala face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female forms of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Guatemala.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in East Timor face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity are legal in East Timor, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Micronesia may face legal difficulties not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples, as same-sex marriage and civil unions are not recognized. Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation has been illegal since 2018.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in Macau, a special administrative region of China, face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. While same-sex sexual activity was decriminalized in 1996, same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples remain ineligible for some legal rights available to opposite-sex couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania enjoy most of the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Pennsylvania. Same-sex couples and families headed by same-sex couples are eligible for all of the protections available to opposite-sex married couples. Pennsylvania was the final Mid-Atlantic state without same-sex marriage, indeed lacking any form of same-sex recognition law until its statutory ban was overturned on May 20, 2014.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in North Macedonia face discrimination and some legal and social challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity have been legal in North Macedonia since 1996, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples.

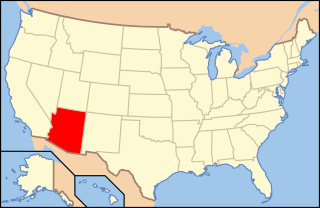

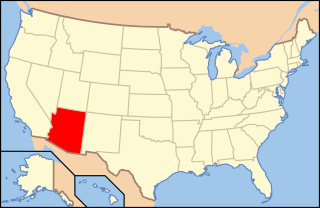

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Arizona may face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Arizona, and same-sex couples are able to marry and adopt. Nevertheless, the state provides only limited protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. Several cities, including Phoenix and Tucson, have enacted ordinances to protect LGBTQ people from unfair discrimination in employment, housing and public accommodations.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Idaho face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ people. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Idaho, and same-sex marriage has been legal in the state since October 2014. State statutes do not address discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is illegal under federal law. A number of cities and counties provide further protections, namely in housing and public accommodations. A 2019 Public Religion Research Institute opinion poll showed that 71% of Idahoans supported anti-discrimination legislation protecting LGBTQ people, and a 2016 survey by the same pollster found majority support for same-sex marriage.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Guam have improved significantly in recent years. Same-sex sexual activity has not been criminalized since 1978, and same-sex marriage has been allowed since June 2015. The U.S. territory now has discrimination protections in employment for both sexual orientation and gender identity. Additionally, federal law has provided for hate crime coverage since 2009. Gender changes are legal in Guam, provided the applicant has undergone sex reassignment surgery.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people generally have limited or highly restrictive rights in most parts of the Middle East, and are open to hostility in others. Sex between men is illegal in 9 of the 18 countries that make up the region. It is punishable by death in four of these 18 countries. The rights and freedoms of LGBT citizens are strongly influenced by the prevailing cultural traditions and religious mores of people living in the region – particularly Islam.

The Kyrgyz anti-LGBT propaganda law has been enacted on 14 August 2023. The bill was introduced on 17 March 2023 and will come into effect on 30 August 2023. The official title of the law is "On introducing amendments to several legal acts of the Kyrgyz Republic". It consists of amendments to the Code of Misdemeanors, the law "On measures to prevent harm to children's health, physical, intellectual, mental, spiritual and moral development in the Kyrgyz Republic", and the law "On Mass Media". The law expands the definition of "information harmful to the health and development of children" to include information that "denies family values, promotes non-traditional sexual relationships, and encourages disrespect for parents or other family members" and subjects those who disseminate such information among minors to fines.