Nikephoros II Phokas, Latinized Nicephorus II Phocas, was Byzantine emperor from 963 to 969. His career, not uniformly successful in matters of statecraft or of war, nonetheless greatly contributed to the resurgence of the Byzantine Empire during the 10th century. In the east, Nikephoros completed the conquest of Cilicia and retook the islands of Crete and Cyprus, opening the path for subsequent Byzantine incursions reaching as far as Upper Mesopotamia and the Levant; these campaigns earned him the sobriquet "pale death of the Saracens".

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Mahdī, better known by his regnal name al-Mahdī, was the third Abbasid Caliph who reigned from 775 to his death in 785. He succeeded his father, al-Mansur.

Bilad al-Sham, often referred to as Islamic Syria or simply Syria in English-language sources, was a province of the Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid, and Fatimid caliphates. It roughly corresponded with the Byzantine Diocese of the East, conquered by the Muslims in 634–647. Under the Umayyads (661–750), Bilad al-Sham was the metropolitan province of the Caliphate and different localities throughout the province served as the seats of the Umayyad caliphs and princes.

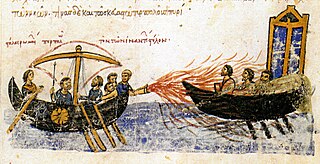

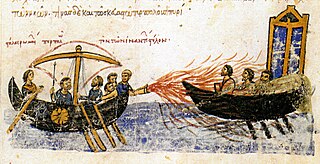

The Arab–Byzantine wars were a series of wars from the 7th to 11th centuries between multiple Arab dynasties and the Byzantine Empire. The Muslim Arab Caliphates conquered large parts of the Christian Byzantine empire and unsuccessfully attacked the Byzantine capital of Constantinople. The frontier between the warring states remained almost static for three centuries of frequent warfare, before the Byzantines were able to recapture some of the lost territory.

Between 780–1180, the Byzantine Empire and the Abbasid & Fatimid caliphates in the regions of Iraq, Palestine, Syria, Anatolia and Southern Italy fought a series of wars for supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean. After a period of indecisive and slow border warfare, a string of almost unbroken Byzantine victories in the late 10th and early 11th centuries allowed three Byzantine Emperors, namely Nikephoros II Phokas, John I Tzimiskes and finally Basil II to recapture territory lost to the Muslim conquests in the 7th century Arab–Byzantine wars under the failing Heraclian Dynasty.

ʿAlī ibn ʾAbū'l-Hayjāʾ ʿAbdallāh ibn Ḥamdān ibn Ḥamdūn ibn al-Ḥārith al-Taghlibī, more commonly known simply by his honorific of Sayf al-Dawla, was the founder of the Emirate of Aleppo, encompassing most of northern Syria and parts of the western Jazira.

The Battle of Krasos took place during the Arab–Byzantine Wars in August 804, between the Byzantines under Emperor Nikephoros I and an Abbasid army under Ibrahim ibn Jibril. Nikephoros' accession in 802 resulted in a resumption of warfare between Byzantium and the Abbasid Caliphate. In late summer 804, the Abbasids had invaded Byzantine Asia Minor for one of their customary raids, and Nikephoros set out to meet them. He was surprised, however, at Krasos and heavily defeated, barely escaping with his own life. A truce and prisoner exchange were afterwards arranged. Despite his defeat, and a massive Abbasid invasion the next year, Nikephoros persevered until troubles in the eastern provinces of the Caliphate forced the Abbasids to conclude a peace.

Melias or Mleh was an Armenian prince who entered Byzantine service and became a distinguished general, founding the theme of Lykandos and participating in the campaigns of John Kourkouas against the Arabs.

Al-ʿAwāṣim was the Arabic term used to refer to the Muslim side of the frontier zone between the Byzantine Empire and the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates in Cilicia, northern Syria and Upper Mesopotamia. It was established in the early 8th century, once the first wave of the Muslim conquests ebbed, and lasted until the mid-10th century, when the Byzantine advance overran it. It comprised the forward marches, comprising a chain of fortified strongholds, known as al-thughūr, and the rear or inner regions of the frontier zone, which was known as al-ʿawāṣim proper. On the Byzantine side, the Muslim marches were mirrored by the institution of the kleisourai and the akritai.

The Theme of Cappadocia was a Byzantine theme encompassing the southern portion of the namesake region from the early 9th to the late 11th centuries.

The Abbasid invasion of Asia Minor in 782 was one of the largest operations launched by the Abbasid Caliphate against the Byzantine Empire. The invasion was launched as a display of Abbasid military might in the aftermath of a series of Byzantine successes. Commanded by the Abbasid heir-apparent, the future Harun al-Rashid, the Abbasid army reached as far as Chrysopolis, across the Bosporus from the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, while secondary forces raided western Asia Minor and defeated the Byzantine forces there. As Harun did not intend to assault Constantinople and lacked ships to do so, he turned back.

The 806 invasion of Asia Minor was the largest of a long series of military operations launched by the Abbasid Caliphate against the Byzantine Empire. The expedition took place in southeastern and central Asia Minor, where the two states shared a long land border.

The Battle of Marash was fought in 953 near Marash between the forces of the Byzantine Empire under the Domestic of the Schools Bardas Phokas the Elder, and of the Hamdanid Emir of Aleppo, Sayf al-Dawla, the Byzantines' most intrepid enemy during the mid-10th century. Despite being outnumbered, the Arabs defeated the Byzantines who broke and fled. Bardas Phokas himself barely escaped through the intervention of his attendants, and suffered a serious wound on his face, while his youngest son and governor of Seleucia, Constantine Phokas, was captured and held a prisoner in Aleppo until his death of an illness some time later. This debacle, coupled with defeats in 954 and again in 955, led to Bardas Phokas' dismissal as Domestic of the Schools, and his replacement by his eldest son, Nikephoros Phokas.

The Battle of Raban was an engagement fought in autumn 958 near the fortress of Raban between the Byzantine army, led by John Tzimiskes, and the forces of the Hamdanid Emirate of Aleppo under the famed emir Sayf al-Dawla. The battle was a major victory for the Byzantines, and contributed to the demise of Hamdanid military power, which in the early 950s had proven a great challenge to Byzantium.

The Battle of Andrassos or Adrassos was fought on 8 November 960 between the Byzantines, led by Leo Phokas the Younger, and the forces of the Hamdanid Emirate of Aleppo under the emir Sayf al-Dawla. It was fought in an unidentified mountain pass in the Taurus Mountains.

The siege of Chandax in 960-961 was the centerpiece of the Byzantine Empire's campaign to recover the island of Crete which since the 820s had been ruled by Muslim Arabs. The campaign followed a series of failed attempts to reclaim the island from the Muslims stretching as far back as 827, only a few years after the initial conquest of the island by the Arabs, and was led by the general and future emperor Nikephoros Phokas. It lasted from autumn 960 until spring 961, when the main Muslim fortress and capital of the island, Chandax was captured. The reconquest of Crete was a major achievement for the Byzantines, as it restored Byzantine control over the Aegean littoral and diminished the threat of Saracen pirates, for which Crete had provided a base of operations.

The Byzantine conquest of Cilicia was a series of conflicts and engagements between the forces of the Byzantine Empire under Nikephoros II Phokas and the Hamdanid ruler of Aleppo, Sayf al-Dawla, over control of the region of Cilicia in southeastern Anatolia. Since the Muslim conquests of the 7th century, Cilicia had been a frontier province of the Muslim world and a base for regular raids against the Byzantine provinces in Anatolia. By the middle of the 10th century, the fragmentation of the Abbasid Caliphate and the strengthening of Byzantium under the Macedonian dynasty allowed the Byzantines to gradually take the offensive. Under the soldier-emperor Nikephoros II Phokas, with the help of the general and future emperor John I Tzimiskes, the Byzantines overcame the resistance of Sayf al-Dawla, who had taken control of the former Abbasid borderlands in northern Syria, and launched a series of aggressive campaigns that in 964–965 recaptured Cilicia. The successful conquest opened the way for the recovery of Cyprus and Antioch over the next few years, and the eclipse of the Hamdanids as an independent power in the region.

The Mesopotamian campaigns of John Tzimiskes were a series of campaigns undertaken by the Byzantine emperor John I Tzimiskes against the Fatimid Caliphate in the Levant and against the Abbasid Caliphate in Syria. Following the weakening and collapse of the Hamdanid Dynasty of Aleppo, much of the Near East lay open to Byzantium, and, following the assassination of Nikephoros II Phokas, the new emperor, John Tzimiskes, was quick to engage the newly successful Fatimid Dynasty over control of the near east and its important cities, namely Antioch, Aleppo, and Caesarea. He also engaged the Hamdanid Emir of Mosul, who was de jure under the suzerainty of the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad and his Buyid overlords, over control of parts of Upper Mesopotamia (Jazira).

The sack of Aleppo in December 962 was carried out by the Byzantine Empire under Nikephoros Phokas. Aleppo was the capital of the Hamdanid emir Sayf al-Dawla, the Byzantines' chief antagonist at the time.