Related Research Articles

An hour is a unit of time conventionally reckoned as 1⁄24 of a day and scientifically reckoned between 3,599 and 3,601 seconds, depending on the speed of Earth's rotation. There are 60 minutes in an hour, and 24 hours in a day.

Astronomy is the oldest of the natural sciences, dating back to antiquity, with its origins in the religious, mythological, cosmological, calendrical, and astrological beliefs and practices of prehistory: vestiges of these are still found in astrology, a discipline long interwoven with public and governmental astronomy. It was not completely separated in Europe during the Copernican Revolution starting in 1543. In some cultures, astronomical data was used for astrological prognostication. The study of astronomy has received financial and social support from many institutions, especially the Christian Church, which was its largest source of support between the 12th century to the Enlightenment.

The zodiac is a belt-shaped region of the sky that extends approximately 8° north or south of the ecliptic, the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year. The paths of the Moon and visible planets are within the belt of the zodiac.

Babylonia was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in central-southern Mesopotamia. A small Amorite-ruled state emerged in 1894 BC, which contained the minor administrative town of Babylon. It was a small provincial town during the Akkadian Empire but greatly expanded during the reign of Hammurabi in the first half of the 18th century BCE and became a major capital city. During the reign of Hammurabi and afterwards, Babylonia was called "the country of Akkad", a deliberate archaism in reference to the previous glory of the Akkadian Empire. It was often involved in rivalry with the older state of Assyria to the north and Elam to the east in Ancient Iran. Babylonia briefly became the major power in the region after Hammurabi created a short-lived empire, succeeding the earlier Akkadian Empire, Third Dynasty of Ur, and Old Assyrian Empire. The Babylonian Empire rapidly fell apart after the death of Hammurabi and reverted to a small kingdom.

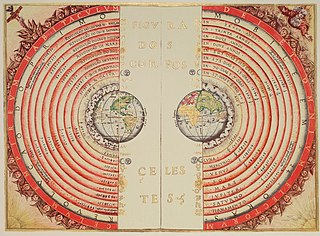

In astronomy, the geocentric model is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets all orbit Earth. The geocentric model was the predominant description of the cosmos in many European ancient civilizations, such as those of Aristotle in Classical Greece and Ptolemy in Roman Egypt.

Sopdet is the ancient Egyptian name of the star Sirius and its personification as an Egyptian goddess. Known to the Greeks as Sothis, she was conflated with Isis as a goddess and Anubis as a god.

The Season of the Inundation or Flood was the first season of the lunar and civil Egyptian calendars. It fell after the intercalary month of Days over the Year and before the Season of the Emergence. In the modern Coptic Calendar, this season lasts from Paoni 12 to Paopi 9.

The Season of the Emergence was the second season of the lunar and civil Egyptian calendars. It fell after the Season of the Inundation and before the Season of the Harvest. In the modern Coptic calendar, the season falls between Paopi 10 and Tobi 10.

The Season of the Harvest or Low Water was the third and final season of the lunar and civil Egyptian calendars. It fell after the Season of the Emergence and before the spiritually dangerous intercalary month, after which the New Year's festivities began the Season of the Inundation (Ꜣḫt). In the modern Coptic calendar it falls between Tobi 11 and Paoni 11.

The heliacal rising or star rise of a star occurs annually, or the similar phenomenon of a planet, when it first becomes visible above the eastern horizon at dawn just before sunrise after a complete orbit of the earth around the sun. Historically, the most important such rising is that of Sirius, which was an important feature of the Egyptian calendar and astronomical development. The rising of the Pleiades heralded the start of the Ancient Greek sailing season, using celestial navigation.

An almanac is an annual publication listing a set of current information about one or multiple subjects. It includes information like weather forecasts, farmers' planting dates, tide tables, and other tabular data often arranged according to the calendar. Celestial figures and various statistics are found in almanacs, such as the rising and setting times of the Sun and Moon, dates of eclipses, hours of high and low tides, and religious festivals. The set of events noted in an almanac may be tailored for a specific group of readers, such as farmers, sailors, or astronomers.

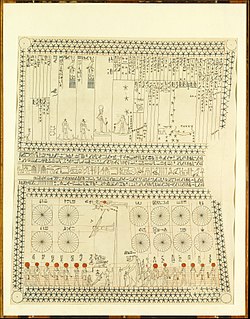

The ancient Egyptian calendar – a civil calendar – was a solar calendar with a 365-day year. The year consisted of three seasons of 120 days each, plus an intercalary month of five epagomenal days treated as outside of the year proper. Each season was divided into four months of 30 days. These twelve months were initially numbered within each season but came to also be known by the names of their principal festivals. Each month was divided into three 10-day periods known as decans or decades. It has been suggested that during the Nineteenth Dynasty and the Twentieth Dynasty the last two days of each decan were usually treated as a kind of weekend for the royal craftsmen, with royal artisans free from work.

Astrological beliefs in correspondences between celestial observations and terrestrial events have influenced various aspects of human history, including world-views, language and many elements of social culture.

The intercalary month or epagomenal days of the ancient Egyptian, Coptic, and Ethiopian calendars are a period of five days in common years and six days in leap years in addition to those calendars' 12 standard months, sometimes reckoned as their thirteenth month. They originated as a periodic measure to ensure that the heliacal rising of Sirius would occur in the 12th month of the Egyptian lunar calendar but became a regular feature of the civil calendar and its descendants. Coptic and Ethiopian leap days occur in the year preceding Julian and Gregorian leap years.

The ancient Egyptian units of measurement are those used by the dynasties of ancient Egypt prior to its incorporation in the Roman Empire and general adoption of Roman, Greek, and Byzantine units of measurement. The units of length seem to have originally been anthropic, based on various parts of the human body, although these were standardized using cubit rods, strands of rope, and official measures maintained at some temples.

Greek astronomy is astronomy written in the Greek language in classical antiquity. Greek astronomy is understood to include the Ancient Greek, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman, and Late Antiquity eras. It is not limited geographically to Greece or to ethnic Greeks, as the Greek language had become the language of scholarship throughout the Hellenistic world following the conquests of Alexander. This phase of Greek astronomy is also known as Hellenistic astronomy, while the pre-Hellenistic phase is known as Classical Greek astronomy. During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, much of the Greek and non-Greek astronomers working in the Greek tradition studied at the Museum and the Library of Alexandria in Ptolemaic Egypt.

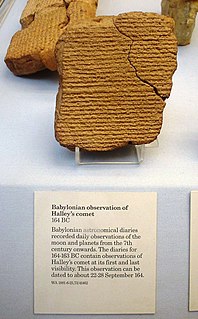

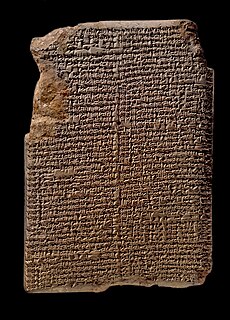

Babylonian astronomy was the study or recording of celestial objects during the early history of Mesopotamia.

MUL.APIN is the conventional title given to a Babylonian compendium that deals with many diverse aspects of Babylonian astronomy and astrology. It is in the tradition of earlier star catalogues, the so-called Three Stars Each lists, but represents an expanded version based on more accurate observation, likely compiled around 1000 BCE. The text lists the names of 66 stars and constellations and further gives a number of indications, such as rising, setting and culmination dates, that help to map out the basic structure of the Babylonian star map.

Egyptian astronomy began in prehistoric times, in the Predynastic Period. In the 5th millennium BCE, the stone circles at Nabta Playa may have made use of astronomical alignments. By the time the historical Dynastic Period began in the 3rd millennium BCE, the 365 day period of the Egyptian calendar was already in use, and the observation of stars was important in determining the annual flooding of the Nile.

Babylonian astronomy collated earlier observations and divinations into sets of Babylonian star catalogues, during and after the Kassite rule over Babylonia. These star catalogues, written in cuneiform script, contained lists of constellations, individual stars, and planets. The constellations were probably collected from various other sources. The earliest catalogue, Three Stars Each, mentions stars of Akkad, of Amurru, of Elam and others. Various sources have theorized a Sumerian origin for these Babylonian constellations, but an Elamite origin has also been proposed. A connection to the star symbology of Kassite kudurru border stones has also been claimed, but whether such kudurrus really represented constellations and astronomical information aside from the use of the symbols remains unclear.

References

- Marshall Clagett, Ancient Egyptian Science: A Source Book, Diane 1989

- Michael Rice, Who's Who in Ancient Egypt, Routledge 1999, p. 54

- Scott B Noegel, Joel Thomas Walker, Brannon M Wheeler, Prayer, Magic, and the Stars in the Ancient and Late Antique World, Penn State Press 2003, pp. 123ff.

- ↑ Clagett, Marshall (1995). Ancient Egyptian Science: Volume 2: Calendars, clocks, and Astronomy. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-214-6.

- ↑ Claget, op.cit. pp.489ff.

- ↑ Noegel et al., op.cit., pp.143f

- ↑ Lehoux, Daryn (2007). Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World. New York: Cambridge University. ISBN 978-0-521-85181-7.

- ↑ "Harkhebi (crater)". babylon-software.com. Babylon. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-08.