Francis Asbury was a British-American Methodist minister who became one of the first two bishops of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States. During his 45 years in the colonies and the newly independent United States, he devoted his life to ministry, traveling on horseback and by carriage thousands of miles to those living on the frontier.

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself nationally. In 1939, the MEC reunited with two breakaway Methodist denominations to form the Methodist Church. In 1968, the Methodist Church merged with the Evangelical United Brethren Church to form the United Methodist Church.

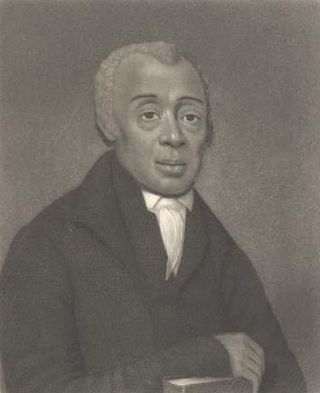

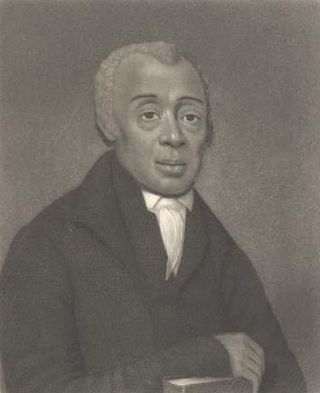

Richard Allen was a minister, educator, writer, and one of the United States' most active and influential black leaders. In 1794, he founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), the first independent Black denomination in the United States. He opened his first AME church in 1794 in Philadelphia.

Peter Cartwright,, also known as "Uncle Peter", "Backwoods Preacher", "Lord's Plowman", "Lord's Breaking-Plow", and "The Kentucky Boy", was an American Methodist, revivalist, preacher, in the Midwest, as well as twice an elected legislator in Illinois. Cartwright, a Methodist missionary, helped start America's Second Great Awakening, personally baptizing twelve thousand converts. Opposed to slavery, Cartwright moved from Kentucky to Illinois, and was elected to the lower house of the Illinois General Assembly in 1828 and 1832. In 1846 Abraham Lincoln defeated Cartwright for a seat in the United States Congress. As a Methodist circuit rider, Cartwright rode circuits in Kentucky and Illinois, as well as Tennessee, Indiana and Ohio. His Autobiography (1856) made him nationally prominent.

Samuel Green was a slave, freedman, and minister of religion. A conductor of the Underground Railroad, he was tried and convicted in 1857 of possessing a copy of the anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe following the Dover Eight incident. He received a ten-year sentence, and was pardoned by the Governor of Maryland Augustus Bradford in 1862, after he served five years.

Robert Carter III was an American planter and politician from the Northern Neck of Virginia. During the colonial period, he sat on the Virginia Governor's Council for roughly two decades. After the American Revolutionary War saw the Thirteen Colonies gain independence from the British Empire as the United States, Carter, influenced by his belief in Baptism, began the largest manumission in the history of the United States prior to the American Civil War.

The Christmas Conference was an historic founding conference of the newly independent Methodists within the United States held just after the American Revolution at Lovely Lane Chapel in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1784.

The Shorthorn breed of cattle originated in the North East of England in the late eighteenth century. The breed was developed as dual-purpose, suitable for both dairy and beef production; however, certain blood lines within the breed always emphasised one quality or the other. Over time, these different lines diverged, and by the second half of the twentieth century, two separate breeds had developed – the Beef Shorthorn, and the Milking Shorthorn. All Shorthorn cattle are coloured red, white, or roan, although roan cattle are preferred by some, and completely white animals are not common. However, one type of Shorthorn has been bred to be consistently white – the Whitebred Shorthorn, which was developed to cross with black Galloway cattle to produce a popular blue roan crossbreed, the Blue Grey.

Daniel Alexander Payne was an American bishop, educator, college administrator and author. A major shaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), Payne stressed education and preparation of ministers and introduced more order in the church, becoming its sixth bishop and serving for more than four decades (1852–1893) as well as becoming one of the founders of Wilberforce University in Ohio in 1856. In 1863, the AME Church bought the college and chose Payne to lead it; he became the first African-American president of a college in the United States and served in that position until 1877.

Samuel D. Burris was a member of the Underground Railroad. He had a family, who he moved to Philadelphia for safety and traveled into Maryland and Delaware to guide freedom seekers north along the Underground Railroad to Pennsylvania.

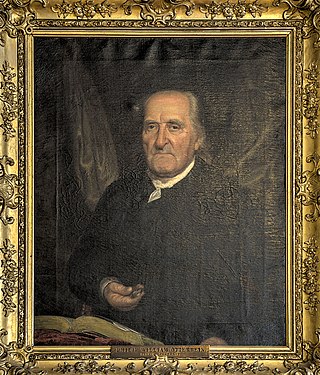

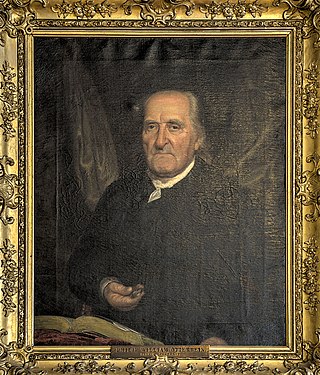

Philip William Otterbein was an American clergyman. He was the founder of the United Brethren in Christ, which merged with the Evangelical Church in 1946 to form the Evangelical United Brethren Church. That church merged with the much larger Methodist Church in 1968, forming the United Methodist Church.

St. George's United Methodist Church, located at the corner of 4th and New Streets, in the Old City neighborhood of Philadelphia, is the oldest Methodist church in continuous use in the United States, beginning in 1769. The congregation was founded in 1767, meeting initially in a sail loft on Dock Street, and in 1769 it purchased the shell of a building which had been erected in 1763 by a German Reformed congregation. At this time, Methodists had not yet broken away from the Anglican Church and the Methodist Episcopal Church was not founded until 1784.

The Perry Hall Mansion is a historic structure located in the area to which it gave its name, Perry Hall, Baltimore County, Maryland, United States. Erected on a hill above the Gunpowder River Valley, the mansion is an excellent example of late colonial and early 19th-century life in eastern Baltimore County.

Lovely Lane United Methodist Church is a historic United Methodist church at 2200 St. Paul Street in the Charles Village neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland, United States.

Freeborn Garrettson was an American clergyman, and one of the first American-born Methodist preachers. He entered the Methodist ministry in 1775 and travelled extensively to evangelize in several states. He was called Methodism's "Paul Revere". Garrettson was an outspoken abolitionist.

Slavery in Maryland lasted over 200 years, from its beginnings in 1642 when the first Africans were brought as slaves to St. Mary's City, to its end after the Civil War. While Maryland developed similarly to neighboring Virginia, slavery declined in Maryland as an institution earlier, and it had the largest free black population by 1860 of any state. The early settlements and population centers of the province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland planters cultivated tobacco as the chief commodity crop, as the market for cash crops was strong in Europe. Tobacco was labor-intensive in both cultivation and processing, and planters struggled to manage workers as tobacco prices declined in the late 17th century, even as farms became larger and more efficient. At first, indentured servants from England supplied much of the necessary labor but, as England's economy improved, fewer came to the colonies. Maryland colonists turned to importing indentured and enslaved Africans to satisfy the labor demand.

Reverend Stephen George Roszel was a Methodist preacher and leading member of the Baltimore Conference.

The history of Methodism in the United States dates back to the mid-18th century with the ministries of early Methodist preachers such as Laurence Coughlan and Robert Strawbridge. Following the American Revolution most of the Anglican clergy who had been in America came back to England. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, sent Thomas Coke to America where he and Francis Asbury founded the Methodist Episcopal Church, which was to later establish itself as the largest denomination in America during the 19th century.

Harry Hosier, better known during his life as "Black Harry", was an African American Methodist preacher during the Second Great Awakening in the early United States. Dr. Benjamin Rush said that, "making allowances for his illiteracy, he was the greatest orator in America". His style was widely influential but he was never formally ordained by the Methodist Episcopal Church or the Rev. Richard Allen's separate African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia.

Harry Gough may refer to: