Related Research Articles

Karl Marx was a German-born philosopher, political theorist, economist, historian, sociologist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His best-known works are the 1848 pamphlet The Communist Manifesto and his three-volume Das Kapital (1867–1894); the latter employs his critical approach of historical materialism in an analysis of capitalism, in the culmination of his intellectual endeavours. Marx's ideas and their subsequent development, collectively known as Marxism, have had enormous influence on modern intellectual, economic and political history.

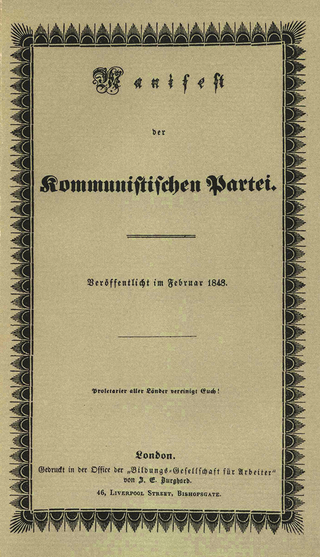

The Communist Manifesto, originally the Manifesto of the Communist Party, is a political pamphlet written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London in 1848. The text is the first and most systematic attempt by Marx and Engels to codify for wide consumption the historical materialist idea that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles", in which social classes are defined by the relationship of people to the means of production. Published amid the Revolutions of 1848 in Europe, the manifesto remains one of the world's most influential political documents.

Friedrich Engels was a German philosopher, political theorist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He was also a businessman and Karl Marx's lifelong friend and closest collaborator, serving as a leading authority on Marxism.

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, with particular strongholds of support in Northern England, the East Midlands, the Staffordshire Potteries, the Black Country and the South Wales Valleys, where working people depended on single industries and were subject to wild swings in economic activity. Chartism was less strong in places, such as Bristol, that had more diversified economies. The movement was fiercely opposed by government authorities, who finally suppressed it.

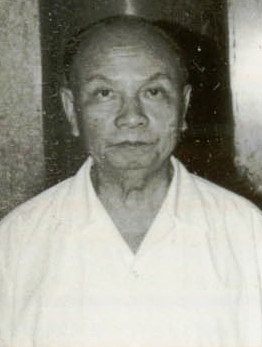

Trường Chinh, born Đặng Xuân Khu; 9 February 1907 – 30 September 1988) was a Vietnamese communist political leader, revolutionary and theoretician. He was one of the key figures of Vietnamese politics and the important Vietnamese leaders for over 40 years. He played a major role in the anti-French colonialism movement and finally after decades of protracted war in Vietnam, the Vietnamese defeated the colonial power. He was the think-tank of the Communist Party who determined the direction of the communist movement, particularly in the anti-French colonialism movement. After the declaration of independence in September 1945, Trường Chinh played an important role in shaping the politics of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and creating the socialist structure of the new Vietnam.

Radicalism was a political movement representing the leftward flank of liberalism between the late 18th and early 20th century. Certain aspects of the movement were precursors to modern-day movements such as social liberalism, social democracy, civil libertarianism, and modern progressivism. This ideology is commonly referred to as "radicalism" but is sometimes referred to as radical liberalism, or classical radicalism, to distinguish it from radical politics. Its earliest beginnings are to be found during the English Civil War with the Levellers and later the Radical Whigs.

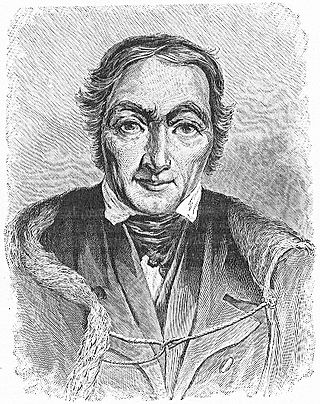

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative movement. The Owenite movement undertook several experiments in the establishment of utopian communities organized according to communitarian and cooperative principles. One of the best known of these efforts, which was unsuccessful, was the project at New Harmony, Indiana, which started in 1825 and was abandoned by 1827. Owenism is also closely associated with the development of the British trade union movement, and with the spread of the Mechanics' Institute movement.

George Julian Harney was a British political activist, journalist, and Chartist leader. He was also associated with Marxism, socialism, and universal suffrage.

The Red Republican was a British socialist newspaper published from 22 June 1850 to 30 November 1850, after which it was renamed The Friend of the People.

Claudia Vera Jones was a Trinidad and Tobago-born journalist and activist. As a child, she migrated with her family to the United States, where she became a Communist political activist, feminist and Black nationalist, adopting the name Jones as "self-protective disinformation". Due to the political persecution of Communists in the US, she was deported in 1955 and subsequently lived in the United Kingdom. Upon arriving in the UK, she immediately joined the Communist Party of Great Britain and would remain a member for the rest of her life. She then founded Britain's first major Black newspaper, the West Indian Gazette, in 1958, and played a central role in founding the Notting Hill Carnival, the second-largest annual carnival in the world.

The Fraternal Democrats was a left-wing political international that promoted working-class internationalism. Based in London, the organisation counted members from half a dozen European countries, many of whom had fled from their home countries. The Fraternal Democrats were largely democratic, republican and socialist in orientation, although they also counted Chartists, communists and nationalists among their ranks. With its membership largely based in Britain, the organisation was never gained a truly international character, as it was unable to establish national sections within other countries. The Revolutions of 1848 resulted in much of its membership dissipating, in order to return to their native countries and participate in the revolutionary events. By the mid-1850s, the FD was succeeded by the International Association, which lay the foundations for the International Workingmen's Association (IWMA).

St Michael's Church is in the civil parish of Baddiley, Cheshire, England. It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed building. The church lies at the end of a lane near to Baddiley Hall, formerly the home of the Mainwaring family. It dates from the early 14th century. The nave and chancel are divided by a pre-Reformation screen and tympanum. The church is one of a 'handful' of timber-framed churches remaining in the country. It continues to be an active Anglican parish church in the diocese of Chester, the archdeaconry of Macclesfield and the deanery of Nantwich. Its benefice is combined with those of St Mary's and St Michael's Church, Burleydam and St Margaret's Church, Wrenbury.

Articles in social and political philosophy include:

Neo-Babouvism is a revolutionary socialist current in French political theory and political action in the 19th century. It hearkened back to the May 1796 Conspiracy of the Equals of Gracchus Babeuf and his associates, who tried to overthrow the Directory in May 1796 during the French Revolution. After Babeuf's execution (1797), his programme of radical Jacobin republicanism and economic collectivism was propagated by Philippe Buonarroti (1761-1837), who had been associated with the Conspiracy of the Equals but had survived. Buonarroti's writings influenced many French revolutionaries in the 1830s and 1840s, among them Théodore Dézamy, Richard Lahautière, Albert Laponneraye and Jean-Jacques Pillot.

Manchester has historically influenced political and social thinking in Britain and been a hotbed for new, radical thinking, particularly during the Industrial Revolution.

Socialism in the United Kingdom is thought to stretch back to the 19th century from roots arising in the English Civil War. Notions of socialism in Great Britain have taken many different forms from the utopian philanthropism of Robert Owen through to the reformist electoral project enshrined in the Labour Party that was founded in 1900 and nationalised a fifth of the British economy in the late 1940s.

Classical Marxism is the body of economic, philosophical, and sociological theories expounded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their works, as contrasted with orthodox Marxism, Marxism–Leninism, and autonomist Marxism which emerged after their deaths. The core concepts of classical Marxism include alienation, base and superstructure, class consciousness, class struggle, exploitation, historical materialism, ideology, revolution; and the forces, means, modes, and relations of production. Marx's political praxis, including his attempt to organize a professional revolutionary body in the First International, often served as an area of debate for subsequent theorists.

The International Workingmen's Association, often called the First International, was a political international which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, social democratic, communist and anarchist groups and trade unions that were based on the working class and class struggle. It was founded in 1864 in a workmen's meeting held in St. Martin's Hall, London. Its first congress was held in 1866 in Geneva.

Karl Friedrich Schapper was a German socialist and labour leader. He was one of the pioneers of the labour movement in Germany and an early associate of Wilhelm Weitling and Karl Marx.

Far-left politics in the United Kingdom have existed since at least the 1840s, with the formation of various organisations following ideologies such as Marxism, revolutionary socialism, communism, anarchism and syndicalism.

References

- ↑ Louise Yeoman, "Helen Macfarlane – the radical feminist admired by Karl Marx", BBC News, 25 November 2012

- ↑ BBC, "Woman with a Past – Helen Macfarlane", broadcast 26 November 2012.

- ↑ BBC, "Women with a Past – Helen Macfarlane"

- ↑ David Black, Helen Macfarlane (2004), p. 44

- ↑ Helen Macfarlane, "Democracy – Remarks on the Times apropos of certain passages in no. 1 of Thomas Carlyle's 'latter-day' pamphlet", Democratic Review, April, May and June 1850.

- ↑ A. R. Schoyen, The Chartist Challenge, p. 203.

- ↑ "Howard Morton" (Helen Macfarlane), "Fine Words (Household of otherwise) Butter No Parsnips". The Red Republican, 20 July 1850. Quoted in BBC Women With A Past (op. cit.).

- ↑ Helen Macfarlane, "Democracy", Democratic Review, op. cit.

- ↑ "Howard Morton" (Helen Macfarlane), "A Birds Eye View of the Glorious British Constitution", Democratic Review, September 1850

- ↑ Reynolds Weekly News 6 October 1850.

- ↑ Communist Manifest (Macfarlane translation, appendix, D. Black, Helen MacFarlane, pp. 137–171.

- ↑ "Literature of the Poor", Times leader, 2 September 1851.

- ↑ Marx to Engels 23 February 1851. Black, pp. 113–120.

- ↑ BBC, Woman With A Past – Helen Macfarlane, op. cit.

- ↑ Macfarlane, "Democracy", op. cit. Quoted in BBC, Woman With A Past – Helen Macfarlane, op. cit.

- ↑ Black, op. cit. pp. 59–73