Diagnosis

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2023) |

Diagnosis on Bases of blood smear and Clinical findings.

Haemorrhagic septicaemia (HS) is one of the most economically important pasteurelloses. [1] [2] Haemorrhagic septicaemia in cattle and buffaloes was previously known to be associated with one of two serotypes of P. multocida : Asian B:2 and African E:2 according to the Carter-Heddleston system, or 6:B and 6:E using the Namioka-Carter system. [2]

The disease occurs mainly in cattle and buffaloes, [2] but has also been reported in goats (Capra aegagrus hircus), [3] [4] [5] African buffalo ( Syncerus nanus ), [6] [ clarification needed ] camels, [7] horses and donkeys ( Equus africanus asinus ), [8] [ clarification needed ] in pigs infected by serogroup B, [3] [9] [10] and in wild elephants (Elephas maximus). [11] [12] [13] Serotypes B:1 and B:3,4 have caused septicaemic disease in antelope ( Antilocapra americana ) and elk ( Cervus canadensis ), respectively. Serotype B:4 was associated with the disease in bison ( Bison bison ). [14] [ clarification needed ]

HS outbreaks were[ when? ] associated with serotype E:2 in Africa and serotype B:2 in Asia. Serotype E:2 was reported in Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Nigeria, Cameroon, the Central African Republic and Zambia. [2] [15] However, it is now[ when? ] inaccurate to associate outbreaks in Africa with serotype E:2, as many outbreaks of HS in Africa have now been associated with serogroup B. [16] In the same manner, serogroup E has been associated with outbreaks in Asia; [16] for instance, one record of "Asian serotype" B:2 was reported in Cameroon. [17] Some reports showed that serotype B:2 may be present in some East African countries. [18] Both serogroups B and E have been reported in Egypt and Sudan. [19]

Natural routes of infection are inhalation and/or ingestion. [2] Experimental transmission has succeeded using intranasal aerosol spray or oral drenching. [2] When subcutaneous inoculation is used experimentally, it results in rapid onset of the disease, a shorter clinical course, and less marked pathological lesions, compared to the longer course of disease and more profound lesions associated with oral drenching and intranasal infection by aerosols. [20]

When HS was introduced for the first time into a geographic area, morbidity and mortality rates were high, [21] approaching 100% unless animals were treated in the very early stages of disease. [18]

A wide variety of clinical signs have been described for HS in cattle and buffaloes. [2] The incubation periods for buffalo calves 4–10 months of age varies according to the route of infection. [20] The incubation period is 12–14 hours for subcutaneous infection, approximately 30 hours for oral infection, and 46–80 hours for natural exposure.

There is variability in the duration of the clinical course of the disease. In the case of experimental subcutaneous infection, the clinical course lasted only a few hours, while it persisted for 2–5 days following oral infection and in buffaloes and cattle that had been exposed to naturally-infected animals. [20] It has also been recorded from field observations that the clinical courses were 4–12 hours for per-acute cases and 2–3 days for acute cases. [22]

Generally, progression of the disease in buffaloes and cattle is divided into three phases. Phase one is characterised by fever, with a rectal temperature of 40–41 °C (104–106 °F), loss of appetite, and depression. Phase two is typified by increased respiratory rate (40–50/minute), laboured breathing, clear nasal discharge (which turns opaque and mucopurulent as the disease progresses), salivation, and submandibular oedema spreading to the pectoral (brisket) region and even to the forelegs. Finally, in phase three, there is typically recumbency, continued acute respiratory distress and terminal septicaemia. [23] The three phases overlap when the disease course is short. In general, buffaloes have a more acute onset of disease than cattle, with a shorter duration. [24]

On post-mortem examination (necropsy), the most obvious gross lesion is subcutaneous oedema in the submandibular and pectoral (brisket) regions. [20] Petechial haemorrhages are found subcutaneously and in the thoracic cavity. In addition, congestion and various degrees of consolidation of the lung may occur. [20] Animals that die within 24–36 hours have only few petechial haemorrhages on the heart and generalised congestion of the lung, while in animals that die after 72 hours, petechial and ecchymotic haemorrhages are more evident and lung consolidation is more extensive. [25]

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2023) |

Diagnosis on Bases of blood smear and Clinical findings.

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2023) |

Sulphadimadine 100 ml orally and injection of oxytetracycline 40 ml for 3 days continuously.

Three factors affect the global distribution of HS: climatic conditions, husbandry practices, and the species of animal. [26] For example, in 1981, Sri Lanka was a good example of different distribution patterns because it had a variety of agroclimatic regions and different husbandry practices. Consequently, Sri Lanka had distinct endemic and non-endemic areas for HS. [2] The disease was almost non-existent where there was a predominance of hills. Here, the climatic conditions were mild, and temperate dairy breeds were reared. In contrast to this, in the warmer dry plains, where there were seasonal heavy rains and indigenous cattle, buffaloes, and zebu cattle, the disease was endemic. Occasional sporadic outbreaks happened in areas with topography, climate, and animals that were between these extremes. [2]

Generally, South Asia is the area of highest prevalence and incidence of HS. [7] This is attributed to radical changes in weather between seasons, animal debilitation caused by seasonal scarcities of fodder, and physical stressors related to the work that these animals perform. [27] The disease also occurs, to a lesser extent, in the Middle East and Africa. Predisposing conditions are not as clearly defined for those locations as in South Asia. [27]

In India from 1974–1986, HS was responsible for the highest mortality rate of infectious diseases in buffaloes and cattle, and was second in its morbidity rate in the same animals. When compared to foot and mouth disease, rinderpest, anthrax and black leg, [28] HS accounted for 58.7% of the deaths due to these five endemic diseases. [28] [29]

Hemorrhagic septicemia is the most important bacterial disease of cattle and buffaloes in Pakistan. [30] In Pakistan, it is a disease of great economic importance; in the Punjab province alone, the financial losses due to HS were estimated to be more than 2.17 billion Pakistani rupees (equivalent to 58 million USD) in 1996. [31] [32] According to farmers' opinions in a participatory disease surveillance (PDS) done in Karachi, HS is more important than foot and mouth disease (FMD), and this is due to the higher mortality rate and the greater economic impact of HS. [33]

Pasteurellosis is an infection with a species of the bacterial genus Pasteurella, which is found in humans and other animals.

Yersinia enterocolitica is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium, belonging to the family Yersiniaceae. It is motile at temperatures of 22–29°C (72–84°F), but becomes nonmotile at normal human body temperature. Y. enterocolitica infection causes the disease yersiniosis, which is an animal-borne disease occurring in humans, as well as in a wide array of animals such as cattle, deer, pigs, and birds. Many of these animals recover from the disease and become carriers; these are potential sources of contagion despite showing no signs of disease. The bacterium infects the host by sticking to its cells using trimeric autotransporter adhesins.

Aviadenoviruses are adenoviruses that affect birds—particularly chickens, ducks, geese, turkeys and pheasants. There are 15 species in this genus. Viruses in this genus cause specific disease syndromes such as Quail Bronchitis (QB), Egg Drop Syndrome (EDS), Haemorrhagic Enteritis (HE), Pheasant Marble Spleen Disease (MSD), and Inclusion Body Hepatitis (IBH). Avian adenoviruses have a worldwide distribution and it is common to find multiple species on a single farm. The most common serogroups are serogroup 1, 2 and 3.

Pasteurella is a genus of Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic bacteria. Pasteurella species are nonmotile and pleomorphic, and often exhibit bipolar staining. Most species are catalase- and oxidase-positive. The genus is named after the French chemist and microbiologist, Louis Pasteur, who first identified the bacteria now known as Pasteurella multocida as the agent of chicken cholera.

Orbivirus is a genus of double-stranded RNA viruses in the family Reoviridae and subfamily Sedoreovirinae. Unlike other reoviruses, orbiviruses are arboviruses. They can infect and replicate within a wide range of arthropod and vertebrate hosts. Orbiviruses are named after their characteristic doughnut-shaped capsomers.

Pasteurella multocida is a Gram-negative, nonmotile, penicillin-sensitive coccobacillus of the family Pasteurellaceae. Strains of the species are currently classified into five serogroups based on capsular composition and 16 somatic serovars (1–16). P. multocida is the cause of a range of diseases in mammals and birds, including fowl cholera in poultry, atrophic rhinitis in pigs, and bovine hemorrhagic septicemia in cattle and buffalo. It can also cause a zoonotic infection in humans, which typically is a result of bites or scratches from domestic pets. Many mammals and birds harbor it as part of their normal respiratory microbiota.

Cefquinome is a fourth-generation cephalosporin with pharmacological and antibacterial properties valuable in the treatment of coliform mastitis and other infections. It is only used in veterinary applications.

Fowl cholera is also called avian cholera, avian pasteurellosis and avian hemorrhagic septicemia.

Pradofloxacin, sold under the brand name Veraflox among others, is a third-generation enhanced spectrum veterinary antibiotic of the fluoroquinolone class. It was developed by Elanco Animal Health GmbH and received approval from the European Commission in April 2011, for prescription-only use in veterinary medicine for the treatment of bacterial infections in dogs and cats.

Wound licking is an instinctive response in humans and many other animals to cover an injury or second degree burn with saliva. Dogs, cats, small rodents, horses, and primates all lick wounds. Saliva contains tissue factor which promotes the blood clotting mechanism. The enzyme lysozyme is found in many tissues and is known to attack the cell walls of many gram-positive bacteria, aiding in defense against infection. Tears are also beneficial to wounds due to the lysozyme enzyme. However, there are also infection risks due to bacteria in the mouth.

Foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) or hoof-and-mouth disease (HMD) is an infectious and sometimes fatal viral disease that affects cloven-hoofed animals, including domestic and wild bovids. The virus causes a high fever lasting two to six days, followed by blisters inside the mouth and near the hoof that may rupture and cause lameness.

Pasteurella dagmatis is a Gram-negative, nonmotile, penicillin-sensitive coccobacillus of the family Pasteurellaceae. P. dagmatis is oxidase and indole positive. Bacteria from this family cause zoonotic infections in humans. These infections manifest themselves as skin or soft tissue infections after an animal bite. It has been known to cause serious disease in immunocompromised patients.

Pasteurella canis is a Gram-negative, nonmotile, penicillin-sensitive coccobacillus of the family Pasteurellaceae. Bacteria from this family cause zoonotic infections in humans, which manifest themselves as skin or soft-tissue infections after an animal bite. It has been known to cause serious disease in immunocompromised patients.

Bovine respiratory disease (BRD) is the most common and costly infectious disease affecting beef cattle in the world. It is a complex, bacterial or viral infection that causes pneumonia in calves which can be fatal. The infection is usually a sum of three codependent factors: stress, an underlying viral infection, and a new bacterial infection. The diagnosis of the disease is complex since there are multiple possible causes.

Culicoides bolitinos is an African species of bloodsucking fly that breeds in the dung of the African buffalo, the blue wildebeest, and cattle (Bosraces). It is considered a possible vector for African horse sickness. It is closely related to Culicoides imicola.

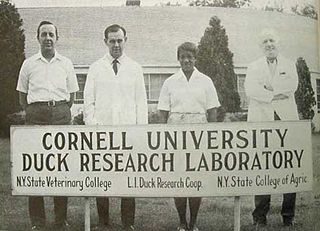

Jessie Isabelle Price was a veterinary microbiologist. She isolated and reproduced the cause of the most common life-threatening disease in duck farming in the 1950s and developed vaccines for this and other avian diseases. A graduate of Cornell University, where she gained a PhD (1959), she worked first at the Cornell Duck Research Laboratory and later at the USGS National Wildlife Health Center. She served as chair of the Predoctoral Minority Fellowship Ad Hoc Review Committee of the American Society for Microbiology (ASM), and as president of Graduate Women in Science.

Cat bites are bites inflicted upon humans, other cats, and other animals by the domestic cat. Data from the United States show that cat bites represent between 5–15% of all animal bites inflicted to humans, but it has been argued that this figure could be the consequence of under-reporting as bites made by cats are considered by some to be unimportant. Though uncommon, cat bites can sometimes cause rabies lead to complications and, very rarely, death.

Eimeria zuernii is a species of the parasite Eimeria that causes diarrheic disease known as eimeriosis in cattle, and mainly affects younger animals. The disease is also commonly referred to as coccidiosis. The parasite can be found in cattle around the globe.

Eimeria bovis is a parasite belonging to the genus Eimeria and is found globally. The pathogen can cause a diarrheic disease in cattle referred to as either eimeriosis or coccidiosis. The infection predominantly cause disease in younger animals.

Bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) is pneumovirus closely related to human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) that is a common cause of respiratory disease in cattle, particularly calves. It is a negative-sense, single-stranded RNA virus that replicates in the cytoplasm of the cell. Similarly to other single-stranded RNA viruses, the genome of BRSV has a high mutation rate, which results in great antigenetic variation. Thus, BRSV can be split into four different subgroups based on antigen expression.