Early life

Henri Buat (as he is usually known; the Anglicized first name "Henry" that is sometimes found in the literature, is not correct) was born in France as the son of colonel Philippe Henri de Fleury de Coulan (or Culan), a Huguenot officer, commanding an infantry regiment of French mercenaries in the service of the Dutch Republic, [3] and Esther de Flins. [4] [5]

Not much is known about his early life. He became a page, first at the court of the Stadtholder Frederik Hendrik as a boy and then at the court of William II, where he underwent military training, [6] before he succeeded his father. [7] He then made a career in the Dutch army, like his father, but in the cavalry. He became a captain commanding the Eskadron Gardes du Corps (Life Guards of the Stadtholder) on November 16, 1646. After the suspension of the Stadtholderate this became the Gardes te paard van de Staten van Zeeland (Horse Guards of the States of Zeeland) in 1660. [8] This regiment of horse was paid for by and recruited in the province of Zeeland, and it was based at Bergen op Zoom. [9] Zeeland was ambivalent in its attitude to the aspirations of the Orangist party. This may explain why Buat became attached to the court of young William III in the early 1660s, while still commanding the regiment, despite the fact that, officially, the Dutch government of the day frowned on the aspirations of the Orangists.

In 1659, he was a volunteer with de Ruyter's expedition to the Sound in the Northern Wars, and at Kerteminde, Buat distinguished himself during the landing of Dutch troops on the Danish island of Funen. [10] [11]

In 1660, Buat was active in promoting the interests of the underage Prince of Orange, William III in Zeeland, and he travelled to England on behalf of the Dowager Princess of Orange, William's guardian. He went to England for the second time in 1662, receiving from Charles II, at the request of the Dowager Princess, the promise of an annuity. [12] He married Elisabeth Maria Musch (not to be confused with her sister Maria Elisabeth), a daughter of Cornelis Musch, the former secretary of the States-General of the Netherlands under the Stadtholderate, and Elisabeth Cats, a daughter of Grand Pensionary Jacob Cats in 1664. [13] This marriage tied him even closer to the Orangist cause, because the Musch family were ardent Orangists.

In October 1665, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War he was appointed by the States of Holland to accompany the cavalry of the French army in its campaign against Munster, to assist it finding accommodation and provisions. [14]

The "Buat Conspiracy"

At the end of 1665, Buat became involved in unofficial correspondence with Sir Gabriel Sylvius, then at the court of Charles II of England but earlier a member of the court of William III's late mother, Mary Stuart, when she was still alive. Sylvius was acting on behalf of Lord Arlington, a minister of Charles II, and this correspondence was originally a diplomatic "back channel" between the Dutch and English governments to explore possibilities of peace. [15] At a relatively early stage, Buat made the Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt fully aware of his correspondence with Sylvius and, through him with Arlington, which not only continued with de Witt's approval, but involved Buat including material provided by de Witt, including possible peace terms. [16]

By February 1660, negotiations had progressed to the stage where Buat brought together Sylvius and Hieronimus van Berverning, and de Witt then invited Charles II to start formal peace negotiations through more orthodox channels. [17] An outline of the English peace proposals was put forward through Buat but, after consulting the States of Holland and the French ambassador, de Witt partly rejected the proposals, but kept negotiations open by demanding a number of clarifications. Buat therefore remained in correspondence with the English government: this correspondence, however, only led to a repeated English insistence that the States General of the Netherlands should send someone to England to negotiate peace terms. Both the States of Holland and France, through its ambassador, rejected this and it was not referred to the States General. Throughout these negotiations, Buat was also in contact with members of the entourage of the Prince, principally the Lord of Zylestein, and leading Orangists, including two Rotterdam regents, Johan Kievit and Ewout van der Horst, although the Prince himself was completely unaware of this. [18]

Arlington and Sylvius had a further design in case the tentative peace negotiations did not bring the desired results. They plotted to bring about an Orangist coup d'état in the Republic, which would overthrow the de Witt regime, restore the stadtholderate, end the war, and renew Anglo-Dutch friendship. Sylvius imprudently committed full details of this plot to paper in a letter for Buat personally, which he sent to Buat together with other letters that were intended for the eyes of de Witt. Buat was confused and handed this compromising letter over to de Witt, together with the more innocent ones. [19] One account suggests that Buat discovered his mistake and returned to de Witt to ask for the "wrong" letter to be returned, but it was already too late: de Witt had presented the incriminating letter to the States of Holland for further action. [20] However, another account suggests that de Witt wished to use Buat to entrap those opposed to him, such as Kievet and van der Horst, and to discredit the Orangists generally. [21]

Buat was arrested (though he was given time to burn most of the incriminating letters, the drafts of which were later discovered in the English state archives). [22] In the criminal procedures that followed it transpired that, besides Buat, only two Rotterdam regents, Johan Kievit and Ewout van der Horst, had sufficiently compromised themselves to be charged. Both escaped to England and were tried in absentia. [23]

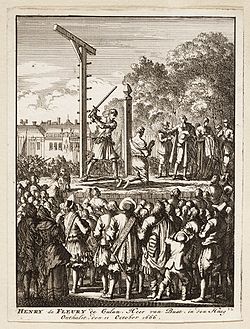

Buat, however, had the misfortune to be tried for treason by the Hof van Holland (the main court of the province of Holland). This in itself was controversial, as the asserted treason was against the Generality, so that the Hoge Raad van Holland en Zeeland (the federal supreme court) might have been more appropriate. Also, according to the opinion of many contemporaries and some later historians, the Executive in the form of the States of Holland exerted undue influence in the proceedings. [24] Even so, the Hof van Holland only voted for Buat's execution by five votes to three in October 1666. This was after the States of Holland had officially urged the reluctant court to do justice, and de Witt had written in a similar vein to some members of the court. [25] In addition, he was convicted after one of the judges who might have voted in his favor (Jacob van der Graeff, the father of the would-be assassin of Johan de Witt, who was executed in 1672), had been forced to recuse himself, so altering the balance in the court. [26]

Many, then and now, think that Buat did not have the intent to commit treason but was the naive stooge of more sinister parties. [27] or the victim of de Witt's hatred of the House of Orange. De Witt's role was ambivalent, as he had clearly supported Buat in the peace negotiations but, when the Orangist conspiracy came to light, had wanted to demonstrate to France that Buat had acted in that matter without his knowledge. [28] Although Buat had been used to further the plans of both Arlington and de Witt and may have been naive, the facts of the planned Orangist coup were clear from Sylvius's letter, even if the verdict was harsh, and the sentence of death was in accordance with a finding of treason. [29] The sentence was publicly executed by Christiaan Hals, the Hague headsman, on October 11, 1666.