First edition | |

| Author | Brendan Gill |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Random House |

Publication date | 1975 |

Here at The New Yorker is a 1975 best-selling book by American writer Brendan Gill, writer and drama critic for The New Yorker magazine.

First edition | |

| Author | Brendan Gill |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Random House |

Publication date | 1975 |

Here at The New Yorker is a 1975 best-selling book by American writer Brendan Gill, writer and drama critic for The New Yorker magazine.

Published on the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of The New Yorker, Gill's book is a semi-autobiographical memoir built around his time as an editor and writer at the magazine and written in the style of the "Talk of the Town" section to which Gill contributed for many years. Much of the book is devoted to anecdotes about his best-known colleagues, such as cartoonists Peter Arno, Charles Addams, and James Thurber; writers Truman Capote, John Updike, S.J. Perelman, and John O'Hara; critics Wolcott Gibbs and Robert Benchley; and editors Katharine White, Harold Ross, and William Shawn.

Gill admits in the introduction that his view of his colleagues is at times highly biased. He detested James Thurber, for instance, calling him a "malicious man" [1] who for his own amusement instigated a number of feuds between New Yorker writers, including one between Gill himself and writer John O'Hara over a book review. [2] Despite respecting Harold Ross for his work on the magazine, Gill reveals his "primitive" and "embarrassing" racism, which excluded blacks from even the most menial positions with the magazine and kept black writers and even article subjects out of its pages. [3] His portrait of William Shawn, however, appeared unsound to some reviewers; Gill portrayed Shawn as a gentle and kind man, but also showed Shawn firing an employee simply for displaying mildly bad taste while off duty. [4] Gill also describes Shawn's well-known prudery, including his reactions to the phrase "cow paddies" and to Henry Green's inspiration for his novel Loving , [5] yet refrains from mentioning that for many years Shawn was leading a double life, with a wife and children in the suburbs and a mistress (Lillian Ross, a colleague who later wrote about the affair) and stepson in the city. [6]

Here at The New Yorker first appeared on The New York Times Best Seller list on March 16, 1975, remaining on the list for sixteen weeks and reaching No. 2 on May 25. [7] It was reprinted in paperback both by Random House and by Berkley Medallion Press. A revised edition was published in 1987 with a new introduction, and was reprinted in 1997, the year of Gill's death.

Reviews of Here at The New Yorker were favorable. Christopher Lehmann-Haupt wrote in The New York Times Book Review that "Mr. Gill kept me in a continual state of mirth", adding that Gill's barbs against his colleagues "are more like a cloud of affectionate bumble bees—these paragraphs full of facts: they settle everywhere and sting all." [4] Other positive reviews were published in The Washington Post , [8] the Christian Science Monitor , [9] and Time magazine, [10] where reviewer Paul Gray said, "A seasoned New Yorker writer can make even New Yorker writers interesting."

Gill's subjects did not all share the enthusiasm of his more positive reviewers. Fellow writer E.J. Kahn called the book "that Gill book" in his own About The New Yorker and Me: A Sentimental Journal, and Nora Ephron said in Esquire (as quoted in Gill's 1997 New York Times obituary) that it "seems to me one of the most offensive books I have read in a long time". [11] Gill wrote in his introduction to the 1987 edition (which was also printed in The New York Times) [12] that Katharine White wept for two days over his portrayal of her, which he defends as accurate. He then accused E. B. White of spearheading a "strenuous campaign of falsehoods" against him, including the claim that William Shawn, the editor of the magazine at the time the book was first published, had not been allowed to read the book before publication. Gill asserted that he had read the book twice in manuscript and had even contributed the book's title, and in turn relates a number of unflattering stories about the recently deceased White, at least two of which were contested by Leo M. Dolenski in a letter to the editor of the Times. Gill's reply to Dolenski's letter instigated a feud between the two. [13]

Elwyn Brooks White was an American writer. He was the author of several highly popular books for children, including Stuart Little (1945), Charlotte's Web (1952), and The Trumpet of the Swan (1970).

James Grover Thurber was an American cartoonist, writer, humorist, journalist, and playwright. He was best known for his cartoons and short stories, published mainly in The New Yorker and collected in his numerous books.

The New Yorker is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for The New York Times. Together with entrepreneur Raoul H. Fleischmann, they established the F-R Publishing Company and set up the magazine's first office in Manhattan. Ross remained the editor until his death in 1951, shaping the magazine's editorial tone and standards.

John Henry O'Hara was an American writer. He was one of America's most prolific writers of short stories, credited with helping to invent The New Yorker magazine short story style. He became a best-selling novelist before the age of 30 with Appointment in Samarra and BUtterfield 8. While O'Hara's legacy as a writer is debated, his work was praised by such contemporaries as Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, and his champions rank him highly among the major under-appreciated American writers of the 20th century. Few college students educated after O'Hara's death in 1970 have discovered him, chiefly because he refused to allow his work to be reprinted in anthologies used to teach literature at the college level.

Harold Wallace Ross was an American journalist who co-founded The New Yorker magazine in 1925 with his wife Jane Grant, and was its editor-in-chief until his death.

William Shawn was an American magazine editor who edited The New Yorker from 1952 until 1987.

Calvin Marshall Trillin is an American journalist, humorist, food writer, poet, memoirist and novelist. He is a winner of the Thurber Prize for American Humor (2012) and an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters (2008).

Veronica Geng was an American humorist, critic, and magazine editor.

Wolcott Gibbs was an American editor, humorist, theatre critic, playwright and writer of short stories, who worked for The New Yorker magazine from 1927 until his death. He is notable for his 1936 parody of Time magazine, which skewered the magazine's inverted narrative structure. Gibbs wrote, "Backward ran sentences until reeled the mind"; he concluded the piece, "Where it all will end, knows God!" He also wrote a comedy, Season in the Sun, which ran on Broadway for 10 months in 1950–51 and was based on a series of stories that originally appeared in The New Yorker.

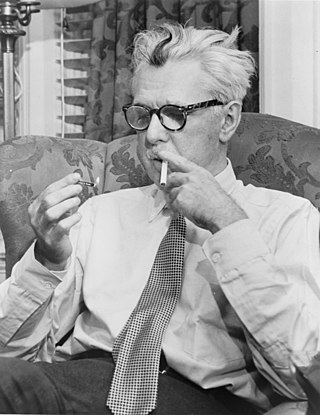

Brendan Gill was an American journalist. He wrote for The New Yorker for more than 60 years. Gill also contributed film criticism for Film Comment, wrote about design and architecture for Architectural Digest and wrote fifteen books, including a popular book about his time at the New Yorker magazine.

Christopher Lehmann-Haupt was an American journalist, editor of The New York Times Book Review, critic, and novelist, based in New York City. He served as senior Daily Book Reviewer from 1969 to 1995.

Robert Adams Gottlieb was an American writer and editor. He was the editor-in-chief of Simon & Schuster, Alfred A. Knopf, and The New Yorker.

Robert Myron Coates was an American novelist, short story writer and art critic. He published five novels; one classic historical work, The Outlaw Years (1930) which deals with the history of the land pirates of the Natchez Trace; a book of memoirs, The View from Here (1960), and two travel books, Beyond the Alps (1962) and South of Rome (1965). During his unusually varied career, Coates explored many different genres and styles of writing and produced three highly remarkable experimental novels, The Eater of Darkness (1926), Yesterday’s Burdens (1933) and The Bitter Season (1946). Highly original and experimental, these novels draw upon expressionism, Dadaism and surrealism. His last two novels—Wisteria Cottage (1948) and The Farther Shore (1955)—are examples of crime fiction. Simultaneously to working as a novelist, Coates maintained a life-long career at the New Yorker, whose staff he joined in 1927. The magazine printed more than a hundred of his short stories many of which were collected in three anthologies; All the Year Round (1943), The Hour after Westerly (1957) and The Man Just ahead of You (1964). Also, from 1937 to 1967, Coates was the New Yorker’s art critic and coined the term “abstract expressionism” in 1946 in reference to the works of Hans Hofmann, Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning and others. He was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1958. Coates was married to sculptor Elsa Kirpal from 1927 to 1946. Their first and only child, Anthony Robertson Coates, was born on March 4, 1934. In 1946, they divorced and Coates married short story writer Astrid Meighan-Peters. He died of cancer of the throat in New York City on February 8, 1973.

Thurber House is a literary center for readers and writers located in Columbus, Ohio, in the historic former home of author, humorist, and New Yorker cartoonist James Thurber. Thurber House is dedicated to promoting the literary arts by presenting quality literary programming; increasing the awareness of literature as a significant art form; promoting excellence in writing; providing support for literary artists; and commemorating Thurber's literary and artistic achievements. The house is individually listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and also as part of the Jefferson Avenue Historic District.

Helen Elna Hokinson was an American cartoonist and a staff cartoonist for The New Yorker. Over a 20-year span, she contributed 68 covers and more than 1,800 cartoons to The New Yorker.

Katharine Sergeant Angell White was an American writer and the fiction editor for The New Yorker magazine from 1925 to 1960. In her obituary, printed in The New Yorker in 1977, William Shawn wrote, "More than any other editor except Harold Ross himself, Katharine White gave The New Yorker its shape, and set it on its course."

Lois Bancroft Long was an American writer for The New Yorker during the 1920s. She was known under the pseudonym "Lipstick" and as the epitome of a flapper.

St. Clair McKelway was a writer and editor for The New Yorker magazine beginning in 1933.

Thomas Vinciguerra was an American journalist, editor, and author. A founding editor of The Week magazine, he published about popular culture, nostalgia and other subjects in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The New Yorker and GQ.

Eugene Kinkead was an American journalist and staff writer and editor at The New Yorker for 58 years. A World War Two war correspondent described as New Yorker founding editor Harold Ross's "favorite gumshoe", Kinkead was an editor of the magazine's "The Talk of the Town" department for many years, and the author of seven books about nature and history, fiction, poetry, profiles, and light verse.