In Greek mythology, Amphiaraus or Amphiaraos was the son of Oicles, a seer, and one of the leaders of the Seven against Thebes. Amphiaraus at first refused to go with Adrastus on this expedition against Thebes as he foresaw the death of everyone who joined the expedition. His wife, Eriphyle, eventually compelled him to go.

In Greek mythology, Adrastus or Adrestus, , was a king of Argos, and leader of the Seven against Thebes. He was the son of the Argive king Talaus, but was forced out of Argos by his dynastic rival Amphiaraus. He fled to Sicyon, where he became king. Later he reconciled with Amphiaraus and returned to Argos as its king.

Tydeus was an Aetolian hero in Greek mythology, belonging to the generation before the Trojan War. He was one of the Seven against Thebes, and the father of Diomedes, who is frequently known by the patronymic Tydides.

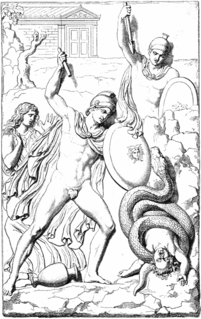

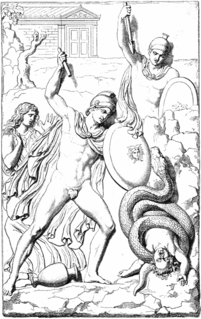

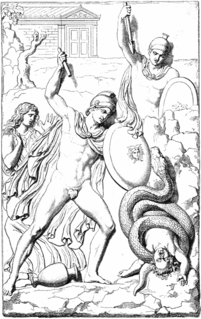

In Greek mythology, Hypsipyle was a queen of Lemnos, and the daughter of King Thoas of Lemnos, and the granddaughter of Dionysus and Ariadne. When the women of Lemnos killed all the males on the island, Hypsipyle saved her father Thoas. She ruled Lemnos when the Argonauts visited the island, and had two sons by Jason, the leader of the Argonauts. Later the women of Lemnos discovered that Thoas had been saved by Hypsipyle and she was sold as a slave to Lycurgus, the king of Nemea, where she became the nurse of the king's infant son Opheltes, who was killed by a serpent while in her care. She is eventually freed from her servitude by her sons.

Panhellenic Games is the collective term for four separate sports festivals held in ancient Greece. The four Games were:

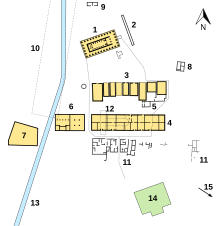

The Nemean Games were one of the four Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece, and were held at Nemea every two years.

Hero cults were one of the most distinctive features of ancient Greek religion. In Homeric Greek, "hero" refers to the mortal offspring of a human and a god. By the historical period, however, the word came to mean specifically a dead man, venerated and propitiated at his tomb or at a designated shrine, because his fame during life or his unusual manner of death gave him power to support and protect the living. A hero was more than human but less than a god, and various kinds of supernatural figures came to be assimilated to the class of heroes; the distinction between a hero and a god was less than certain, especially in the case of Heracles, the most prominent, but atypical hero.

Nemea is an ancient site in the northeastern part of the Peloponnese, in Greece. Formerly part of the territory of Cleonae in ancient Argolis, it is today situated in the regional unit of Corinthia. The small village of Archaia Nemea is immediately southwest of the archaeological site, while the new town of Nemea lies to the west.

The Seven against Thebes were seven champions in Greek mythology who made war on Thebes. They were chosen by Adrastus, the king of Argos, to be the captains of an Argive army whose purpose was to restore Oedipus' son Polynices to the Theban throne. Adrastus, although always the leader of the expedition against Thebes, was not always counted as one of the Seven champions. Usually the Seven were Polynices, Tydeus, Amphiaraus, Capaneus, Parthenopaeus, Hippomedon, and Adrastus or Eteoclus, whenever Adrastus is excluded. They tried and failed to take Thebes, and all but Adrastus died in the attempt.

In Greek mythology, Pronax was one of the sons of Talaus and Lysimache, a brother of Adrastus and Eriphyle, and the father of Lycurgus and Amphithea. According to some accounts, he died before the war of the Seven against Thebes, and the Nemean Games were instituted in his honor.

The Thebaid is a Latin epic poem written by the Roman poet Statius. Published in the early 90s AD, it contains 12 books and recounts the clash of two brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, over the throne of the Greek city of Thebes. After Polynices is sent into exile, he forges an alliance of seven Greek princes and embarks on a military campaign against his brother.

A heroön or heroon, also latinized as heroum, is a shrine dedicated to an ancient Greek or Roman hero and used for the commemoration or cult worship of the hero. They were often erected over his or her supposed tomb or cenotaph.

The Amphiareion of Oropos, situated in the hills 6 km southeast of the fortified port of Oropos, was a sanctuary dedicated in the late 5th century BCE to the hero Amphiaraos, where pilgrims went to seek oracular responses and healing. It became particularly successful during the 4th century BCE, to judge from the intensive building at the site. The hero Amphiaraos was a descendant of the seer Melampos and initially refused to participate in the attack on Thebes because he could foresee that it would be a disaster. In some versions of the myth, the earth opens and swallows the chariot of Amphiaraos, transforming him into a chthonic hero. Today the site is found east of the modern town Markopoulo Oropou in the Oropos municipality of Attica, Greece

In Greek mythology, Opheltes, also called Archemorus, was a son of Lycurgus of Nemea. His mother is variously given as Eurydice, Nemea, or Amphithea. As an infant, he was killed by a serpent at Nemea. Funeral games were held in the boy's honor, and these were supposed to have been the origin of the Nemean Games.

The Archaeological Museum of Nemea is a museum in Nemea, Corinthia, Greece. It was constructed by the University of California and given to the Greek State in 1984. The museum is located at the entrance to the Archaeological site of Nemea. Exhibits finds from this site and the surrounding areas, from Cooper Age (Chalcolithic) to early Byzantine era.

In Greek mythology, Lycurgus, also spelled Lykurgos or Lykourgos, was the son of Pheres, and the husband of Eurydice by whom he was the father of Opheltes. In the earliest account, Lycurgus was a priest of Nemean Zeus, while in later accounts he was a king of Nemea.

The archaeological site of Menelaion is located approximately 5 km from the modern city of Sparta. The geographical structure of this site includes a hill complex. The archaic name of the place is mentioned as Therapne.

The theme of death within ancient Greek art has continued from the Early Bronze Age all the way through to the Hellenistic period. The Greeks used architecture, pottery, and funerary objects as different mediums through which to portray death. These depictions include mythical deaths, deaths of historical figures, and commemorations of those who died in war. This page includes various examples of the different types of mediums in which death is presented in Greek art.

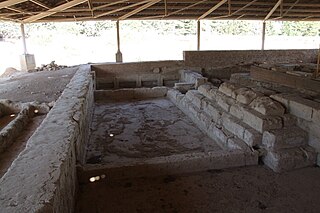

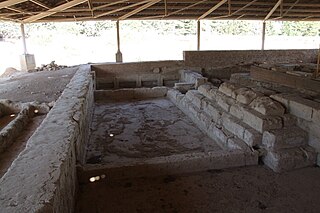

The Nemean baths are an athletic bathing house at the Panhellenic sanctuary of Nemea in the Argolis. The baths are located on the south most part of the Hellenistic complex. They are directly west of the similarly dated Xenon, which served as athlete's lodging.

Hypsipyle is a partially preserved tragedy by Euripides, about the legend of queen Hypsipyle of Lemnos, daughter of King Thoas. It was one of his last and most elaborate plays. It was performed c. 411–407, along with The Phoenician Women which survives in full, and the lost Antiope.