Northumbria was an early medieval Anglian kingdom in what is now Northern England and South Scotland.

Scandinavian York or Viking York is a term used by historians for what is now Yorkshire during the period of Scandinavian domination from late 9th century until it was annexed and integrated into England after the Norman Conquest; in particular, it is used to refer to York, the city controlled by these kings and earls. The Kingdom of Jórvík was closely associated with the longer-lived Kingdom of Dublin throughout this period.

Hexham Abbey is a Grade I listed church dedicated to St Andrew, in the town of Hexham, Northumberland, in the North East of England. Originally built in AD 674, the Abbey was built up during the 12th century into its current form, with additions around the turn of the 20th century. Since the dissolution of the monasteries in 1537, the Abbey has been the parish church of Hexham. In 2014 the Abbey regained ownership of its former monastic buildings, which had been used as Hexham magistrates' court, and subsequently developed them into a permanent exhibition and visitor centre, telling the story of the Abbey's history.

A sceat or sceatta was a small, thick silver coin minted in England, Frisia, and Jutland during the Anglo-Saxon period that normally weighed 0.8–1.3 grams. It is now more commonly known in England as an 'early penny'.

Eanred was king of Northumbria in the early ninth century.

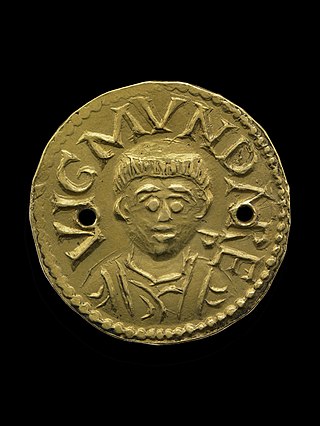

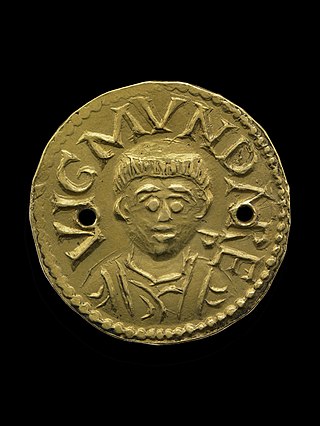

Wigmund was a medieval Archbishop of York, who was consecrated in 837 and died in 854.

Wulfhere was Archbishop of York between 854 and 900.

Eardwulf was king of Northumbria from 796 to 806, when he was deposed and went into exile. He may have had a second reign from 808 until perhaps 811 or 830. Northumbria in the last years of the eighth century was the scene of dynastic strife between several noble families: in 790, king Æthelred I attempted to have Eardwulf assassinated. Eardwulf's survival may have been viewed as a sign of divine favour. A group of nobles conspired to assassinate Æthelred in April 796 and he was succeeded by Osbald: Osbald's reign lasted only twenty-seven days before he was deposed and Eardwulf became king on 14 May 796.

ÆthelredII was king of Northumbria in the middle of the ninth century, but his dates are uncertain. N. J. Higham gives 840 to 848, when he was killed, with an interruption in 844 when Rædwulf usurped the throne, but was killed the same year fighting against the Vikings. Barbara Yorke agrees, and adds that Æthelred was the son of his predecessor, Eanred, but dates his death 848 or 849. D. P. Kirby thinks that an accession date of 844 is more likely, but notes that a coin of Eanred dated stylistically no earlier than 850 may require a more radical revision of dates. David Rollason accepts the coin evidence, and dates Æthelred's reign from c.854 to c. 862, with Rædwulf's usurpation in 858.

Rædwulf was king of Northumbria for a short time. His ancestry is not known, but it is possible that he was a kinsman of Osberht and Ælla.

The history of the English penny can be traced back to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of the 7th century: to the small, thick silver coins known to contemporaries as pæningas or denarii, though now often referred to as sceattas by numismatists. Broader, thinner pennies inscribed with the name of the king were introduced to Southern England in the middle of the 8th century. Coins of this format remained the foundation of the English currency until the 14th century.

Beonna was King of East Anglia from 749. He is notable for being the first East Anglian king whose coinage included both the ruler's name and his title. The end-date of Beonna's reign is not known, but may have been around 760. It is thought that he shared the kingdom with another ruler called Alberht and possibly with a third man, named Hun. Not all experts agree with these regnal dates, or the nature of his kingship: it has been suggested that he may have ruled alone from around 758.

The Liudhard medalet is a gold Anglo-Saxon coin or small medal found sometime before 1844 near St Martin's Church in Canterbury, England. It was part of the Canterbury-St Martin's hoard of six items. The coin, along with other items found with it, now resides in the World Museum Liverpool. Although some scholarly debate exists on whether or not all the items in the hoard were from the same grave, most historians who have studied the object conclude that they were buried together as a necklace in a 6th-century woman's grave. The coin is set in a mount so that it could be worn as jewellery, and has an inscription on the obverse or front surrounding a robed figure. The inscription refers to Liudhard, a Frankish bishop who accompanied Bertha from Francia to England when she married Æthelberht the king of Kent. The reverse side of the coin has a double-barred cross, or patriarchal cross, with more lettering.

Coinage in Anglo-Saxon England refers to the use of coins, either for monetary value or for other purposes, in Anglo-Saxon England.

Viking coinage was used during the Viking Age of northern Europe. Prior to the usage and minting of coins, the Viking economy was predominantly a bullion economy, where the weight and size of a particular metal is used as a method of evaluating value, as opposed to the value being determined by the specific type of coin. By the ninth century, the Viking raids brought them into contact with cultures well familiarised with the use of coins in economies of Europe, hence influencing the Vikings own production of coins.

The styca was a small coin minted in pre-Viking Northumbria, originally in base silver and subsequently in a copper alloy. Production began in the 790s and continued until the 850s, though the coin remained in circulation until the Viking conquest of Northumbria in 867.

Elizabeth Jean Elphinstone Pirie was a British numismatist specialising in ninth-century Northumbrian coinage, and museum curator, latterly as Keeper of Archaeology at Leeds City Museum from 1960 to 1991. She wrote eight books and dozens of articles throughout her career. She was a fellow of the Royal Numismatic Society, president of the Yorkshire Numismatic Society and a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

The Kirkoswald Hoard is a ninth-century hoard of 542 copper alloy coins of the Kingdom of Northumbria and a silver trefoil ornament, which were discovered amongst tree roots in 1808 within the parish of Kirkoswald in Cumbria, UK.

The St Leonard's Place hoard was a hoard of c. 10,000 early medieval Northumbrian coins known as stycas, discovered by workers during construction work at St Leonard's Place in York in 1842. Many of the coins were subsequently acquired by the Yorkshire Museum.

!["An Account of the Discovery at Hexham ..." [proceed to p. 367] (Archaeologia, or, Miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity - Society of Antiquaries of London. Volume 25, 1834) Archaeologia, or, Miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity - Society of Antiquaries of London. Volume 25, 1834 (IA s2id13276840).pdf](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/eb/Archaeologia%2C_or%2C_Miscellaneous_tracts_relating_to_antiquity_-_Society_of_Antiquaries_of_London._Volume_25%2C_1834_%28IA_s2id13276840%29.pdf/page1-220px-Archaeologia%2C_or%2C_Miscellaneous_tracts_relating_to_antiquity_-_Society_of_Antiquaries_of_London._Volume_25%2C_1834_%28IA_s2id13276840%29.pdf.jpg)