Castile or Castille is a territory of imprecise limits located in Spain. The use of the concept of Castile relies on the assimilation of a 19th-century determinist geographical notion, that of Castile as Spain's centro mesetario with a long-gone historical entity of diachronically variable territorial extension.

Ferdinand IV of Castile called the Summoned, was King of Castile and León from 1295 until his death.

Prince or Princess of Asturias is the main substantive title used by the heir apparent, or heir presumptive to the Spanish Crown. According to the Spanish Constitution of 1978:

Article 57.2: The Crown Prince, from the time of his birth or the event conferring this position upon him, shall hold the title of Prince of Asturias and the other titles traditionally held by the heir to the Crown of Spain.

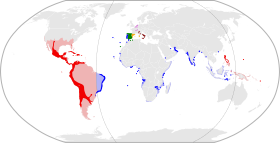

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It achieved a global scale, controlling vast portions of the Americas, Africa, various islands in Asia and Oceania, as well as territory in other parts of Europe. It was one of the most powerful empires of the early modern period, becoming known as "the empire on which the sun never sets". At its greatest extent in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Spanish Empire covered over 13 million square kilometres, making it one of the largest empires in history.

A viceroyalty was an entity headed by a viceroy. It dates back to the Spanish conquest of the Americas in the sixteenth century.

The Kingdom of Aragon was a medieval and early modern kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, corresponding to the modern-day autonomous community of Aragon, in Spain. It should not be confused with the larger Crown of Aragon, which also included other territories—the Principality of Catalonia, the Kingdom of Valencia, the Kingdom of Majorca, and other possessions that are now part of France, Italy, and Greece—that were also under the rule of the King of Aragon, but were administered separately from the Kingdom of Aragon.

The Crown of Aragon was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of Barcelona and ended as a consequence of the War of the Spanish Succession. At the height of its power in the 14th and 15th centuries, the Crown of Aragon was a thalassocracy controlling a large portion of present-day eastern Spain, parts of what is now southern France, and a Mediterranean empire which included the Balearic Islands, Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia, Malta, Southern Italy, and parts of Greece.

A Real Audience, or simply an Audience, was an appellate court in Spain and its empire. The name of the institution literally translates as Royal Audience. The additional designation chancillería was applied to the appellate courts in early modern Spain. Each audiencia had oidores.

The Principality of Catalonia was a medieval and early modern state in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula. During most of its history it was in dynastic union with the Kingdom of Aragon, constituting together the Crown of Aragon. Between the 13th and the 18th centuries, it was bordered by the Kingdom of Aragon to the west, the Kingdom of Valencia to the south, the Kingdom of France and the feudal lordship of Andorra to the north and by the Mediterranean Sea to the east. The term Principality of Catalonia was official until the 1830s, when the Spanish government implemented the centralized provincial division, but remained in popular and informal contexts. Today, the term Principat (Principality) is used primarily to refer to the autonomous community of Catalonia in Spain, as distinct from the other Catalan Countries, and usually including the historical region of Roussillon in Southern France.

The County of Barcelona was a polity in northeastern Iberian Peninsula, originally located in the southern frontier region of the Carolingian Empire. In the 10th century, the Counts of Barcelona progressively achieved independence from Frankish rule, becoming hereditary rulers in constant warfare with the Islamic Caliphate of Córdoba and its successor states. The counts, through marriage, alliances and treaties, acquired or vassalized the other Catalan counties and extended their influence over Occitania. In 1164, the County of Barcelona entered a personal union with the Kingdom of Aragon. Thenceforward, the history of the county is subsumed within that of the Crown of Aragon, but the city of Barcelona remained preeminent within it.

Ferdinand II was King of Aragon from 1479 until his death in 1516. As the husband and co-ruler of Queen Isabella I of Castile, he was also King of Castile from 1475 to 1504. He reigned jointly with Isabella over a dynastically unified Spain; together they are known as the Catholic Monarchs. Ferdinand is considered the de facto first king of Spain, and was described as such during his reign, even though, legally, Castile and Aragon remained two separate kingdoms until they were formally united by the Nueva Planta decrees issued between 1707 and 1716.

The House of Lara is a noble family from the medieval Kingdom of Castile. Two of its branches, the Duques de Nájera and the Marquesado de Aguilar de Campoo were considered Grandees of Spain. The Lara family gained numerous territories in Castile, León, Andalucía, and Galicia and members of the family moved throughout the former Spanish colonies, establishing branches as far away as the Philippines and Argentina.

The Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes is an Isabelline style Franciscan monastery in Toledo, in Castile-La Mancha, Spain, built by the Catholic Monarchs (1477–1504).

The Treaty of Villafáfila is a treaty signed by Ferdinand the Catholic in Villafáfila on 27 June 1506 and by Philip the Handsome in Benavente, Zamora, on 28 June.

Enrique García Hernán is a Spanish historian of the culture of early modern Europe. His research examines the interaction of religious sentiment, political thought and international relations in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It attempts to bridge the gap between the study of forms of cultural and intellectual expression and the realities of political, diplomatic and military organization. He is a Corresponding Fellow of the Royal Academy of History, member of the Board of Directors (Vocal) of the Spanish Commission for Military History, and Fellow (Académico) of the Ambrosiana Academy of Milan. His current academic affiliation is as a research professor in the Institute of History, within the Center for Humanities and Social Sciences at the Spanish National Research Council. The Spanish National Research Council is the largest public institution dedicated to research in Spain and the third largest in Europe.

The Spanish institutions of the Ancien Régime were the superstructure that, with some innovations, but above all through the adaptation and transformation of the political, social and economic institutions and practices pre-existing in the different Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula in the Late Middle Ages, presided over the historical period that broadly coincides with the Modern Age: from the Catholic Monarchs to the Liberal Revolution and which was characterized by the features of the Ancien Régime in Western Europe: a strong monarchy, a estamental society and an economy in transition from feudalism to capitalism.

The Secretary of State or Secretary of State and of the Office was the title given in Spain to the King's ministers during the Ancient Regime of Spain, between the 17th century and the mid-19th century, when it was definitively replaced by the term "minister". It should be clarified that the Secretaries of State and of the Office of State, i.e. the heads of the Secretariat in charge of foreign affairs, were commonly known as Secretaries of State and, although they had the same rank as the other Secretaries of the Office, the Secretary of State assumed the leading role, presiding over the meetings of the ministers and attending to the most important matters.