Related Research Articles

The History of Equatorial Guinea is marked by centuries of colonial domination by the Portuguese, British and Spanish colonial empires, and by the local kingdoms.

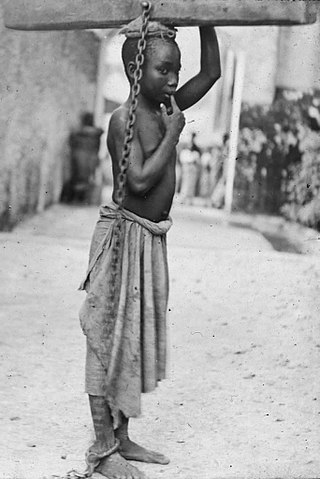

In law and human rights, slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labor. Slavery typically involves compulsory work with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavement is the placement of a person into slavery.

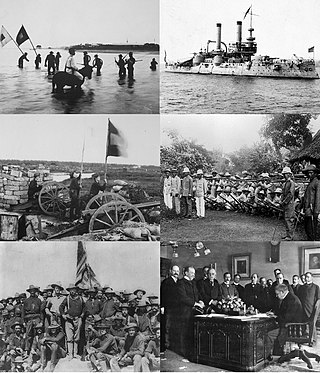

The Spanish–American War began in the aftermath of the internal explosion of USS Maine in Havana Harbor in Cuba, leading to United States intervention in the Cuban War of Independence. The war led to the United States emerging predominant in the Caribbean region, and resulted in U.S. acquisition of Spain's Pacific possessions. It led to United States involvement in the Philippine Revolution and later to the Philippine–American War.

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Passage, and existed from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The vast majority of those who were transported in the transatlantic slave trade were people from Central and West Africa who had been sold by other West Africans to Western European slave traders, while others had been captured directly by the slave traders in coastal raids; Europeans gathered and imprisoned the enslaved at forts on the African coast and then brought them to the Americas. Except for the Portuguese, European slave traders generally did not participate in the raids because life expectancy for Europeans in sub-Saharan Africa was less than one year during the period of the slave trade. The colonial South Atlantic and Caribbean economies were particularly dependent on labour for the production of sugarcane and other commodities. This was viewed as crucial by those Western European states which, in the late 17th and 18th centuries, were vying with one another to create overseas empires.

The history of the Caribbean reveals the significant role the region played in the colonial struggles of the European powers since the 15th century. In the modern era, it remains strategically and economically important. In 1492, Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean and claimed the region for Spain. The following year, the first Spanish settlements were established in the Caribbean. Although the Spanish conquests of the Aztec empire and the Inca empire in the early sixteenth century made Mexico and Peru more desirable places for Spanish exploration and settlement, the Caribbean remained strategically important.

On March 2, 1901, the Platt Amendment was passed as part of the 1901 Army Appropriations Bill. It stipulated seven conditions for the withdrawal of United States troops remaining in Cuba at the end of the Spanish–American War, and an eighth condition that Cuba signs a treaty accepting these seven conditions. It defined the terms of Cuban–U.S. relations essentially to be an unequal one of U.S. dominance over Cuba.

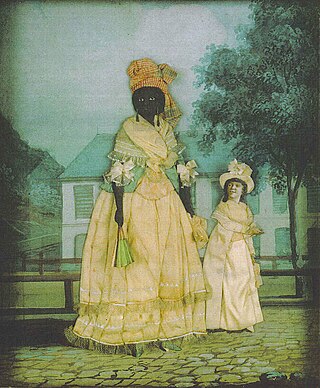

Slavery in the colonial history of the United States, from 1526 to 1776, developed from complex factors, and researchers have proposed several theories to explain the development of the institution of slavery and of the slave trade. Slavery strongly correlated with the European colonies' demand for labor, especially for the labor-intensive plantation economies of the sugar colonies in the Caribbean and South America, operated by Great Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, and the Dutch Republic.

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

The Ostend Manifesto, also known as the Ostend Circular, was a document written in 1854 that described the rationale for the United States to purchase Cuba from Spain while implying that the U.S. should declare war if Spain refused. Cuba's annexation had long been a goal of U.S. slaveholding expansionists. At the national level, American leaders had been satisfied to have the island remain in weak Spanish hands so long as it did not pass to a stronger power such as Britain or France. The Ostend Manifesto proposed a shift in foreign policy, justifying the use of force to seize Cuba in the name of national security. It resulted from debates over slavery in the United States, manifest destiny, and the Monroe Doctrine, as slaveholders sought new territory for the expansion of slavery.

The Ten Years' War, also known as the Great War and the War of '68, was part of Cuba's fight for independence from Spain. The uprising was led by Cuban-born planters and other wealthy natives. On 10 October 1868, sugar mill owner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes and his followers proclaimed independence, beginning the conflict. This was the first of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Little War (1879–1880) and the Cuban War of Independence (1895–1898). The final three months of the last conflict escalated with United States involvement, leading to the Spanish–American War.

In the British colonies in North America and in the United States before the abolition of slavery in 1865, free Negro or free Black described the legal status of African Americans who were not enslaved. The term was applied both to formerly enslaved people (freedmen) and to those who had been born free.

Slavery in the Spanish American colonies was an economic and social institution which existed throughout the Spanish Empire including Spain itself. In its American territories, early Spanish monarchs put forth laws against enslaving Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Queen Isabella outlawed the enslavement of Native Americans in the Spanish colonies of the New World because she viewed the natives as subjects of the Spanish monarchy. While Spain displayed an early abolitionist stance towards the Indigenous, some instances of illegal Native American slavery continued to be practiced by rogue individuals, particularly until the New Laws of 1543 which expressly prohibited it.

The Partido Independiente de Color (PIC) was a Cuban political party composed almost entirely of African former slaves. It was founded in 1908 by African veterans of the Cuban War of Independence. In 1912, the PIC led a revolt in the eastern province of Oriente. The revolt was crushed and the party disbanded. It is believed Esteban Montejo, subject of Miguel Barnets "Biografía de un cimarrón," was a member of this party, or had close associates who were.

Racism in Cuba refers to racial discrimination in Cuba. In Cuba, dark skinned Afro-Cubans are the only group on the island referred to as black while lighter skinned, mixed race, Afro-Cuban mulattos are often not characterized as fully black or fully white. Race conceptions in Cuba are unique because of its long history of racial mixing and appeals to a "raceless" society. The Cuban census reports that 65% of the population is white while foreign figures report an estimate of the number of whites at anywhere from 40 to 45 percent. This is likely due to the self-identifying mulattos who are sometimes designated officially as white. A common myth in Cuba is that every Cuban has at least some African ancestry, influenced by historical mestizaje nationalism. Given the high number of immigrants from Europe in the 20th century, this is far from true. Several pivotal events have impacted race relations on the island. Using the historic race-blind nationalism first established around the time of independence, Cuba has navigated the abolition of slavery, the suppression of black clubs and political parties, the revolution and its aftermath, and the special period.

Slavery in Latin America was an economic and social institution that existed in Latin America from before the colonial era until its legal abolition in the newly independent states during the 19th century. However, it continued illegally in some regions into the 20th century. Slavery in Latin America began in the pre-colonial period when indigenous civilizations, including the Maya and Aztec, enslaved captives taken in war. After the conquest of Latin America by the Spanish and Portuguese, of the nearly 12 million slaves that were shipped across the Atlantic, over 4 million enslaved Africans were brought to Latin America. Roughly 3.5 million of those slaves were brought to Brazil.

Slavery in Cuba was a portion of the larger Atlantic Slave Trade that primarily supported Spanish plantation owners engaged in the sugarcane trade. It was practised on the island of Cuba from the 16th century until it was abolished by Spanish royal decree on October 7, 1886.

Slavery was widespread in the Philippine islands before the archipelago was conquered by the Spanish Empire. It was also common during Spanish rule. Policies banning slavery that the Spanish crown established for its empire in the Americas were not extended to its territories in the Spanish East Indies, which included the Philippines. The Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico) ruled the Philippines administratively, and the terminus of the Manila galleon in Acapulco saw the importation of Filipino slaves to Mexico, who were labeled chinos.

Esteban Mesa Montejo was a Cuban slave who escaped to freedom before slavery was abolished on the island in 1886. He lived as a maroon in the mountains until that time. He also served in the war of independence in Cuba. He is known for having his biography published in 1966, in both Spanish and English, several years before his death and when he was already more than 100 years old. He lived to be 112. In 1997 Michael Zeuske, a German historian and field researcher of Cuban slavery and life histories, found evidence of Esteban Montejo's real date of birth in the baptismal registers - not 1860, but 1868

Slavery in Florida is more central to Florida's history than it is to almost any other state. Florida's purchase by the United States from Spain in 1819 was primarily a measure to strengthen the system of slavery on Southern plantations, by denying potential runaways the formerly safe haven of Florida.

References

- ↑ Blackmar (1900) , p. 21

- 1 2 Lynch (1992) , pp. 69–74

- ↑ Lynch (1992) , p. 77

- 1 2 Pérez (1999) , p. 25

- ↑ Pérez (1999) , pp. 86, 89

- ↑ "Cuban Independence Movement | Cuban history". Encyclopedia of Britannica.

- ↑ Schmidt-Nowara (2004) , p. 5

- ↑ Pérez (1999) , p. 90

- ↑ Scott (1998) , p. 688

- ↑ Scott & Zeuske (2002) , p. 675

- ↑ Scott (1998) , p. 692

- ↑ Scott & Zeuske (2002) , p. 670

- ↑ Scott (1998) , p. 691–696

- ↑ Scott (1998) , p. 704

- ↑ Scott & Zeuske (2002) , p. 676

- ↑ Scott (1998) , p. 699

- ↑ Scott (1998) , p. 693

- ↑ Scott & Zeuske (2002) , p. 680

- ↑ Scott & Zeuske (2002) , pp. 677–680

- ↑ Hennessy (1963) , p. 350

- ↑ Hennessy (1963) , p. 346

Bibliography

- Blackmar, Frank W. (1900). "Spanish colonial policy". Publications of the American Economic Association. 3rd Series. 1 (3): 112–143. JSTOR 2485793.

- Hennessy, C. A. M. (1963). "The roots of Cuban nationalism". International Affairs. 39 (3): 345–359. doi:10.2307/2611204. JSTOR 2611204.

- Lynch, J. (1992). "The institutional framework of colonial Spanish America". Journal of Latin American Studies. 24: 69–81. doi:10.1017/s0022216x00023786. JSTOR 156946.

- Pérez, Louis A. (1999). On Becoming Cuban: Identity, Nationality, and Culture . Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807824870.

- Schmidt-Nowara, Christopher (2004). "'La España ultramarina': colonialism and nation building in nineteenth-century Spain". European History Quarterly. 34 (2): 191–214. doi:10.1177/0265691404042507. S2CID 145675694.

- Scott, Rebecca J. (1998). "Race, labor and citizenship in Cuba: a view from the sugar district of Cienfuegos 1886-1909". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 78 (4): 687–728. doi:10.2307/2518424. JSTOR 2518424.

- Scott, Rebecca J.; Zeuske, Michael (2002). "Property in writing, property on the ground: pigs, horses, land, and citizenship in the aftermath of slavery, Cuba, 1880–1909". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 44 (4): 669–703. doi:10.1017/s0010417502000324. JSTOR 3879519. S2CID 145173481.