Related Research Articles

A mining accident is an accident that occurs during the process of mining minerals or metals. Thousands of miners die from mining accidents each year, especially from underground coal mining, although accidents also occur in hard rock mining. Coal mining is considered much more hazardous than hard rock mining due to flat-lying rock strata, generally incompetent rock, the presence of methane gas, and coal dust. Most of the deaths these days occur in developing countries, and rural parts of developed countries where safety measures are not practiced as fully. A mining disaster is an incident where there are five or more fatalities.

Abercanaid is a small village in the county borough of Merthyr Tydfil, Glamorgan, Wales, United Kingdom with a population of about 5,060. It is situated 2.5 miles (4.0 km) south of Merthyr town centre and is west of Pentrebach, across the River Taff and north of Troedyrhiw. The Taff Trail runs through the village, adjacent to the path of the disused Glamorganshire Canal, which was an important in transporting iron and coal during the industrial boom in which the South Wales Valleys prospered.

Chesterton is a former mining village on the edge of Newcastle-under-Lyme, in the Newcastle-under-Lyme district, in Staffordshire, England.

The Oaks explosion, which happened at a coal mine in West Riding of Yorkshire on 12 December 1866, remains the worst mining disaster in England. A series of explosions caused by firedamp ripped through the underground workings at the Oaks Colliery at Hoyle Mill near Stairfoot in Barnsley killing 361 miners and rescuers. It was the worst mining disaster in the United Kingdom until the 1913 Senghenydd explosion in Wales.

The Gresford disaster occurred on 22 September 1934 at Gresford Colliery, near Wrexham, when an explosion and underground fire killed 261 men. Gresford is one of Britain's worst coal mining disasters: a controversial inquiry into the disaster did not conclusively identify a cause, though evidence suggested that failures in safety procedures and poor mine management were contributory factors. Further public controversy was caused by the decision to seal the colliery's damaged sections permanently, meaning that the bodies of only 8 of the miners were ever recovered. Two of the three rescue men who died were brought out leaving the third body in situ until recovery operations began the following year.

Clifton Hall Colliery was one of two coal mines in Clifton on the Manchester Coalfield, historically in Lancashire which was incorporated into the City of Salford in Greater Manchester, England in 1974. Clifton Hall was notorious for an explosion in 1885 which killed around 178 men and boys.

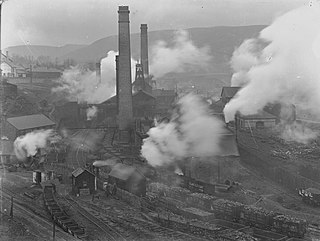

The North Staffordshire Coalfield was a coalfield in Staffordshire, England, with an area of nearly 100 square miles (260 km2), virtually all of it within the city of Stoke on Trent and the borough of Newcastle-under-Lyme, apart from three smaller coalfields, Shaffalong and Goldsitch Moss Coalfields near Leek and the Cheadle Coalfield. Coal mining in North Staffordshire began early in the 13th century, but the industry grew during the Industrial Revolution when coal mined in North Staffordshire was used in the local Potteries ceramics and iron industry.

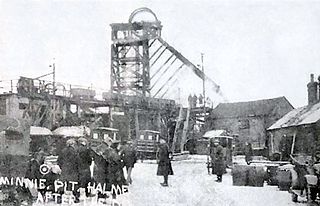

The Minnie Pit disaster was a coal mining accident that took place on 12 January 1918 in Halmer End, Staffordshire, in which 155 men and boys died. The disaster, which was caused by an explosion due to firedamp, is the worst ever recorded in the North Staffordshire Coalfield. An official investigation never established what caused the ignition of flammable gases in the pit.

The Drummond Mine explosion, also called the Drummond Colliery Disaster, was a mining accident that happened in Westville, Pictou County, Nova Scotia on May 13, 1873.

The Lancashire Coalfield in North West England was an important British coalfield. Its coal seams were formed from the vegetation of tropical swampy forests in the Carboniferous period over 300 million years ago.

The Bedford Colliery disaster occurred on Friday 13 August 1886 when an explosion of firedamp caused the death of 38 miners at Bedford No.2 Pit, at Bedford, Leigh in what then was Lancashire. The colliery, sunk in 1884 and known to be a "fiery pit", was owned by John Speakman.

Sir William Galloway was a Scottish mining engineer, professor and industrialist.

Predominantly centred on Hanley and Burslem, in what became the federation of Stoke-on-Trent, the 1842 Pottery Riots took place in the midst of the 1842 General Strike, and both are credited with helping to forge trade unionism and direct action as a powerful tool in British industrial relations.

The Cadeby Main Pit Disaster was a coal mining accident on 9 July 1912 which occurred at Cadeby Main Colliery in Cadeby, West Riding of Yorkshire, England, killing 91 men. Early in the morning of 9 July an explosion in the south-west part of the Cadeby Main pit killed 35 men, with three more dying later due to their injuries. Later in the same day, after a rescue party was sent below ground, another explosion occurred, killing 53 men of the rescue party.

The Abercarn colliery disaster was a catastrophic explosion within the Prince of Wales Colliery in the Welsh village of Abercarn, on 11 September 1878, killing 268 men and boys. The cause was assumed to have been the ignition of firedamp by a safety lamp. The disaster is the third worst for loss of life to occur within the South Wales Coalfield.

The Sneyd Colliery Disaster was a coal mining accident on 1 January 1942 in Burslem in the English city of Stoke-on-Trent. An underground explosion occurred at 7:50 am, caused by sparks from wagons underground igniting coal dust. A total of 57 men and boys died.

Bentley Colliery was a coal mine in Bentley, near Doncaster in South Yorkshire, England, that operated between 1906 and 1993. In common with many other mines, it suffered disasters and accidents. The worst Bentley disaster was in 1931 when 45 miners were killed after a gas explosion. The site of the mine has been converted into a woodland.

John Brass was a manager and later director of Houghton Main Colliery Co Ltd. According to the Colliery Year Book and Coal Trades Directory he was "one of the most prominent figures in the South Yorkshire coal mining industry". He held significant posts in the mining, gas and coke industries both in South Yorkshire and nationally. Between 1934 and 1937 he was one of the assessors in the Gresford disaster inquiry and, along with the other assessor, published dissenting reports to the main inquiry.

The Diglake Colliery Disaster, was a coal-mining disaster at what was Audley Colliery in Bignall End, North Staffordshire, on 14 January 1895. A flood of water rushed into the mine and caused the deaths of 77 miners. Only three bodies were recovered, with efforts to retrieve the dead hampered by floodwater. 73 bodies are still entombed underground.

The Cymmer Colliery explosion occurred in the early morning of 15 July 1856 at the Old Pit mine of the Cymmer Colliery near Porth, Wales, operated by George Insole & Son. The underground gas explosion resulted in a "sacrifice of human life to an extent unparalleled in the history of coal mining of this country" in which 114 men and boys were killed. Thirty-five widows, ninety-two children, and other dependent relatives were left with no immediate means of support.

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Holditch Colliery". exploringthepotteries.org.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "HOLDITCH. Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire. 2nd. July, 1937" (PDF). cmhrc.co.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Holditch colliery". staffspasttrack.org.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Holditch Colliery". myweb.tiscali.co.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Lumsdon, John. "HOLDITCH COLIERY EXPLOSION 1937". healeyhero.co.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "HOLDITCH COLLIERY DISASTER". HC Deb 05 July 1937 vol 326 cc33-6. 5 July 1937. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "The Holditch Coliery Disaster 1937". rangersfchistory.co.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Lumsdon, John. "Holditch Colliery Explosion 1937". northstaffsminers.btik.com. Retrieved 31 August 2010.[ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ "Holditch Colliery (11 deaths)". myweb.tiscali.co.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2010.