Hugh or Hugo (died 24 December 1144) was the Latin Archbishop of Edessa from about 1120 until his death. He is sometimes called "Hugh II", although he is the only known Edessene bishop named Hugh. The chronicler Bar Hebraeus calls him "Papyas" and "the metropolitan of the Franks". [1] Most of the Christians in his province would have been Armenians not in communion with Rome; they only recognized papal authority in 1145. Hugh defended his city during the siege of Edessa of 1144 while Count Joscelin II of Edessa was absent. He was killed when the city fell to Zengi, atabeg of Mosul.

Hugh was originally from Flanders. On his way to Jerusalem he stopped at the Abbey of Cluny and became an associate of the Cluniac order, being invested by Abbot Hugh with "the society of all the goods of the congregation", what the Flemish Hugh later called a "confraternity of prayer" with Cluny. [2] [3] In 1120, he donated some relics—a finger of Saint Stephen and a tooth of John the Baptist—to Cluny under Abbot Pons. According to an account of their donation, the Tractatus de Reliquiis Sancti Stephani Cluniacum Delatis, Hugh feared for his soul because he was keeping the holy relics in a city under constant threat of Muslim attack. Only after he was visited three times by the three patron saints of Cluny in visions that he mistook for dreams did Hugh decide to turn the relics over to Cluny. He gave them to Gilduin du Puiset, former prior of Cluny, who gave them to the monk Frotmund, who conveyed them to Cluny in a crystal glass casket. [4] Hugh also acquired relics of Saints Thaddeus of Edessa and Abgar he sent to the archbishop of Reims, Ralph, in 1123. [2] The letter Hugh addressed to the archbishop has survived, been edited and published. Hugh calls himself Hugo, Dei gratia Edessenae archiepiscopus, that is, archbishop "by the grace of God". [5]

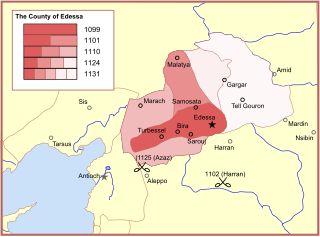

Hugh's diocese shrank sometime before 1134, when the Crusaders re-established the ancient Archdiocese of Hierapolis based on the city of Dülük, which they called La Tuluppe. Its territory was taken from that of Edessa. [6]

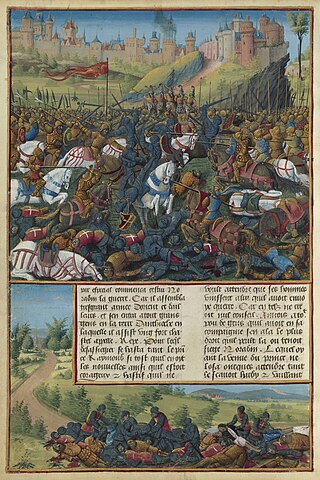

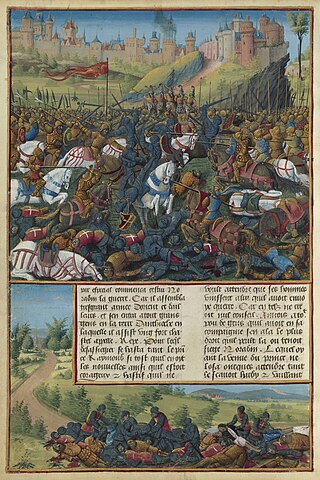

On 28 November 1144, Zengi surrounded the walled city of Edessa while the ruling count was away with his army. In the absence of the ruler and the best fighting men, Archbishop Hugh was charged with the defence of the city. He had the loyal support of the Armenian bishop John and the Syriac bishop Basil. Later chroniclers, including William of Tyre, accused him of refusing to spend from his treasury to pay the arrears of his soldiers, and blame the city's fall on his avarice. [7] Hugh also ordered the defenders of the citadel not to open the gates unless he arrived in person. After the walls had been breached on 24 December, dozens of citizens were crushed in the mad rush to the citadel as the gates remained shut. Hugh himself was killed either in the stampede or by Zengi's soldiers as he tried to reach the citadel. [1] [2] [8] [9] [10]

Bernard of Clairvaux, O.Cist., venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar, and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercian Order.

Year 1144 (MCXLIV) was a leap year starting on Saturday of the Julian calendar.

Melisende was Queen of Jerusalem from 1131 to 1153, and regent for her son between 1153 and 1161, while he was on campaign. She was the eldest daughter of King Baldwin II of Jerusalem, and the Armenian princess Morphia of Melitene.

The Second Crusade (1147–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe. The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa in 1144 to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crusade (1096–1099) by the future King Baldwin I of Jerusalem in 1098. While it was the first Crusader state to be founded, it was also the first to fall.

Fulk, also known as Fulk the Younger, was King of Jerusalem with his wife, Queen Melisende, from 1131 until his death in 1143. Previously, he was Count of Anjou, as Fulk V, from 1109 to 1129. During Fulk's reign, the Kingdom of Jerusalem reached its largest territorial extent.

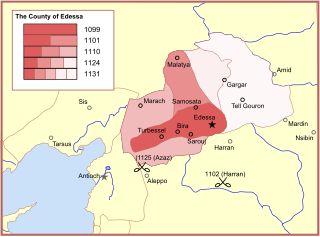

The County of Edessa was a 12th-century Crusader state in Upper Mesopotamia. Its seat was the city of Edessa.

Edessa was an ancient city (polis) in Upper Mesopotamia, in what is now Urfa or Şanlıurfa, Turkey. It was founded during the Hellenistic period by Macedonian general and self proclaimed king Seleucus I Nicator, founder of the Seleucid Empire. He named it after an ancient Macedonian capital. The Greek name Ἔδεσσα (Édessa) means "tower in the water". It later became capital of the Kingdom of Osroene, and continued as capital of the Roman province of Osroene. In Late Antiquity, it became a prominent center of Christian learning and seat of the Catechetical School of Edessa. During the Crusades, it was the capital of the County of Edessa.

Joscelin II was the fourth and last ruling count of Edessa. He was son of his predecessor, Joscelin I, and Beatrice, daughter of Constantine I of Armenia.

The siege of Edessa took place from 28 November to 24 December 1144, resulting in the fall of the capital of the County of Edessa to Zengi, the atabeg of Mosul and Aleppo. This event was the catalyst for the Second Crusade.

Matthew of Edessa was an Armenian historian in the 12th century from the city of Edessa. Matthew was the superior abbot of Karmir Vank, near the town of Kaysun, east of Marash (Germanicia), the former seat of Baldwin of Boulogne. He relates much about the Bagratuni Kingdom of Armenia, the early Crusades, and the battles between Byzantines and Arabs for the possession of parts of northern Syria and eastern Asia Minor.

Shaizar or Shayzar is a town in northern Syria, administratively part of the Hama Governorate, located northwest of Hama. Nearby localities include, Mahardah, Tremseh, Kafr Hud, Khunayzir and Halfaya. According to the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Shaizar had a population of 5,953 in the 2004 census.

Alberic of Ostia (1080–1148) was a Benedictine monk, diplomat and Cardinal Bishop of Ostia from 1138 to 1148. He was one of the most important people in the administration of Pope Eugenius III, especially due to his diplomatic skills.

William of Bures was Prince of Galilee from 1119 or 1120 to his death. He was descended from a French noble family which held estates near Paris. William and his brother, Godfrey, were listed among the chief vassals of Joscelin of Courtenay, Prince of Galilee, when their presence in the Holy Land was first recorded in 1115. After Joscelin received the County of Edessa from Baldwin II of Jerusalem in 1119, the king granted the Principality of Galilee to William. He succeeded Eustace Grenier as constable and bailiff in 1123. In his latter capacity, he administered the kingdom during the Baldwin II's captivity for more than a year, but his authority was limited.

The Council of Acre met at Palmarea, near Acre, a major city of the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, on 24 June 1148. The Haute Cour of Jerusalem met with recently arrived crusaders from Europe, to decide on the best target for the crusade. The Second Crusade had been called after the fall of Edessa to Zengi in 1144. In 1147, armies led by Conrad III of Germany and Louis VII of France began their separate journeys to the east. Conrad arrived at Acre in April 1148, and Louis marched south from Antioch.

Gilo of Toucy, also called Gilo of Paris or Gilo of Tusculum, was a French poet and cleric. A priest before he became a monk at Cluny, he was appointed cardinal-bishop of Tusculum sometime between 1121 and 1123. He served as a papal legate on four occasions: to Poland and Hungary around 1124, to Carinthia in 1126, to the Crusader states in 1128 or 1129 and to Aquitaine from 1131 until 1137. He took the side of the Antipope Anacletus II in the papal schism of 1130 and was deposed as cardinal-bishop by the Second Lateran Council in 1139.

Ralph of Domfront was the archbishop of Mamistra and second Latin patriarch of Antioch from 1135 until 1140. William of Tyre describes him as "a military man, very magnificent and generous, a great favourite of the common people and with those of knightly birth."

Benedict was the first archbishop of Edessa of the Latin rite. He was probably appointed soon after Count Baldwin I founded the county of Edessa in 1098. He was consecrated by Patriarch Daimbert of Jerusalem in December 1099. He may have replaced a Byzantine bishop, if one was still in residence after the Byzantines lost the city in 1087. Although the highest-ranking churchman in the county of Edessa, Benedict was subordinated to the patriarch of Antioch in accordance with the 6th-century Notitiae episcopatuum. The contemporary historian William of Tyre calls Benedict, Daimbert and the Antiochene patriarch, Bernard, three "distinguished lights of the church".

Gilduin of Le Puiset was the son of Hugh I of Le Puiset and Alice of Montlhéry, daughter of Guy I of Montlhéry. Monk at St. Martin-des-Champs, prior at Cluny Abbey, prior at Lurey-le-Bourg, abbot of St. Mary of the Valley of Jehosaphat.

Athanasius VII bar Qatra was the Patriarch of Antioch, and head of the Syriac Orthodox Church from 1139 until his death in 1166.

Basil bar Shumna was the Syriac Orthodox metropolitan archbishop of Edessa from 1143 until his death. He wrote a Syriac chronicle covering the years from 1118 until his death, which is now lost but was used as a source by Michael the Great and the anonymous author of the Chronicle of 1234.