Tláloc is the god of rain in Aztec religion. He was also a deity of earthly fertility and water, worshipped as a giver of life and sustenance. This came to be due to many rituals, and sacrifices that were held in his name. He was feared, but not maliciously, for his power over hail, thunder, lightning, and even rain. He is also associated with caves, springs, and mountains, most specifically the sacred mountain where he was believed to reside. Cerro Tláloc is very important in understanding how rituals surrounding this deity played out. His followers were one of the oldest and most universal in ancient Mexico.

A chacmool is a form of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican sculpture depicting a reclining figure with its head facing 90 degrees from the front, supporting itself on its elbows and supporting a bowl or a disk upon its stomach. These figures possibly symbolised slain warriors carrying offerings to the gods; the bowl upon the chest was used to hold sacrificial offerings, including pulque, tamales, tortillas, tobacco, turkeys, feathers, and incense. In Aztec examples, the receptacle is a cuauhxicalli. Chacmools were often associated with sacrificial stones or thrones. The chacmool form of sculpture first appeared around the 9th century AD in the Valley of Mexico and the northern Yucatán Peninsula.

Child sacrifice is the ritualistic killing of children in order to please or appease a deity, supernatural beings, or sacred social order, tribal, group or national loyalties in order to achieve a desired result. As such, it is a form of human sacrifice. Child sacrifice is thought to be an extreme extension of the idea that the more important the object of sacrifice, the more devout the person rendering it.

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/priestly figure, spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherein a monarch's servants are killed in order for them to continue to serve their master in the next life. Closely related practices found in some tribal societies are cannibalism and headhunting. Human sacrifice is also known as ritual murder.

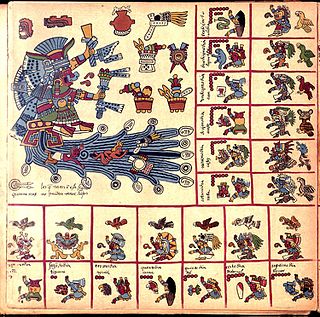

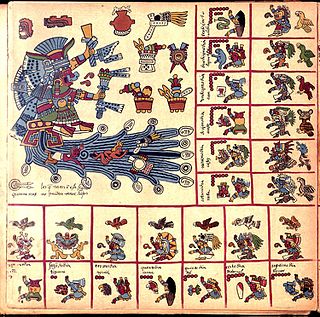

Chalchiuhtlicue is an Aztec deity of water, rivers, seas, streams, storms, and baptism. Chalchiuhtlicue is associated with fertility, and she is the patroness of childbirth. Chalchiuhtlicue was highly revered in Aztec culture at the time of the Spanish conquest, and she was an important deity figure in the Postclassic Aztec realm of central Mexico. Chalchiuhtlicue belongs to a larger group of Aztec rain gods, and she is closely related to another Aztec water god called Chalchiuhtlatonal.

Huitzilopochtli is the solar and war deity of sacrifice in Aztec religion. He was also the patron god of the Aztecs and their capital city, Tenochtitlan. He wielded Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent, as a weapon, thus also associating Huitzilopochtli with fire.

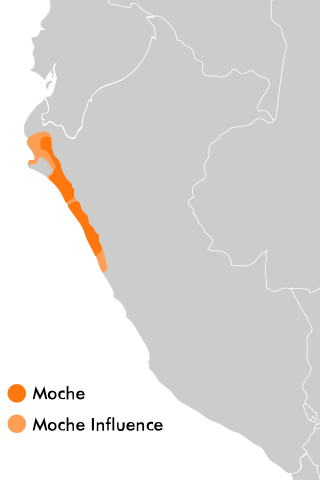

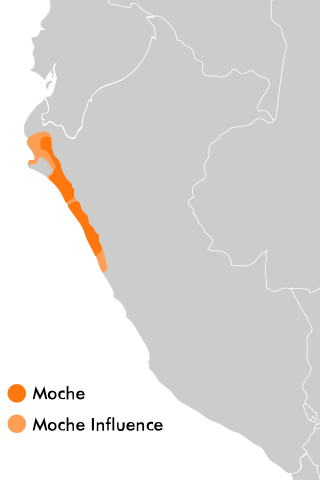

The Moche civilization flourished in northern Peru with its capital near present-day Moche, Trujillo, Peru from about 100 to 700 AD during the Regional Development Epoch. While this issue is the subject of some debate, many scholars contend that the Moche were not politically organized as a monolithic empire or state. Rather, they were likely a group of autonomous polities that shared a common culture, as seen in the rich iconography and monumental architecture that survives today.

Momia Juanita, also known as the Lady of Ampato, is the well-preserved frozen body of a girl from the Inca Empire who was killed as a human sacrifice to the Inca gods sometime between 1440 and 1480, when she was approximately 12–15 years old. She was discovered on the dormant stratovolcano Mount Ampato in 1995 by anthropologist Johan Reinhard and his Peruvian climbing partner, Miguel Zárate. Another of her nicknames, Ice Maiden, derives from the cold conditions and freezing temperatures that preserved her body on Mount Ampato.

A tzompantli or skull rack was a type of wooden rack or palisade documented in several Mesoamerican civilizations, which was used for the public display of human skulls, typically those of war captives or other sacrificial victims. It is a scaffold-like construction of poles on which heads and skulls were placed after holes had been made in them. Many have been documented throughout Mesoamerica, and range from the Epiclassic through early Post-Classic. In 2015 archeologists announced the discovery of the Huey Tzompantli, with more than 650 skulls, in the archeological zone of the Templo Mayor in Mexico City.

Pre-Columbian art refers to the visual arts of indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, North, Central, and South Americas from at least 13,000 BCE to the European conquests starting in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The pre-Columbian era continued for a time after these in many places, or had a transitional phase afterwards. Many types of perishable artifacts that were once very common, such as woven textiles, typically have not been preserved, but Precolumbian monumental sculpture, metalwork in gold, pottery, and painting on ceramics, walls, and rocks have survived more frequently.

Sacrifice was a religious activity in Maya culture, involving the killing of humans or animals, or bloodletting by members of the community, in rituals superintended by priests. Sacrifice has been a feature of almost all pre-modern societies at some stage of their development and for broadly the same reason: to propitiate or fulfill a perceived obligation towards the gods.

The Aztec religion is a polytheistic and monistic pantheism in which the Nahua concept of teotl was construed as the supreme god Ometeotl, as well as a diverse pantheon of lesser gods and manifestations of nature. The popular religion tended to embrace the mythological and polytheistic aspects, and the Aztec Empire's state religion sponsored both the monism of the upper classes and the popular heterodoxies.

Human sacrifice was common in many parts of Mesoamerica, so the rite was nothing new to the Aztecs when they arrived at the Valley of Mexico, nor was it something unique to pre-Columbian Mexico. Other Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Purépechas and Toltecs, and the Maya performed sacrifices as well and from archaeological evidence, it probably existed since the time of the Olmecs, and perhaps even throughout the early farming cultures of the region. However, the extent of human sacrifice is unknown among several Mesoamerican civilizations. What distinguished Aztec practice from Maya human sacrifice was the way in which it was embedded in everyday life. These cultures also notably sacrificed elements of their own population to the gods.

Capacocha or Qhapaq hucha was an important sacrificial rite among the Inca that typically involved the sacrifice of children. Children of both sexes were selected from across the Inca empire for sacrifice in capacocha ceremonies, which were performed at important shrines distributed across the empire, known as huacas, or wak'akuna.

Most of the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica such as the Olmec, Maya, Mixtec, Zapotec and Aztec cultures practiced some kind of taking of human trophies during warfare. Captives taken during war would often be taken to their captors' city-states where they would be ritually tortured and sacrificed. These practices are documented by a rich material of iconographic and archaeological evidence from across Mesoamerica.

The Children of Llullaillaco, also known as the Mummies of Llullaillaco, are three Inca child mummies discovered on 16 March 1999 by Johan Reinhard and his archaeological team near the summit of Llullaillaco, a 6,739 m (22,110 ft) stratovolcano on the Argentina–Chile border. The children were sacrificed in an Inca religious ritual that took place around the year 1500. In this ritual, the three children were drugged with coca and alcohol then placed inside a small chamber 1.5 metres (5 ft) beneath the ground, where they were left to die. Archaeologists consider them as being among the best-preserved mummies in the world.

The Lady of Cao is a name given to a female Moche mummy discovered at the archeological site El Brujo, which is located about 45 km north of Trujillo in the La Libertad Region of Peru.

In the Aztec culture, a tecpatl was a flint or obsidian knife with a lanceolate figure and double-edged blade, with elongated ends. Both ends could be rounded or pointed, but other designs were made with a blade attached to a handle. It can be represented with the top half red, reminiscent of the color of blood, in representations of human sacrifice and the rest white, indicating the color of the flint blade.

During the pre-Columbian era, human sacrifice in Maya culture was the ritual offering of nourishment to the gods and goddesses. Blood was viewed as a potent source of nourishment for the Maya deities, and the sacrifice of a living creature was a powerful blood offering. By extension, the sacrifice of human life was the ultimate offering of blood to the gods, and the most important Maya rituals culminated in human sacrifice. Generally, only high-status prisoners of war were sacrificed, and lower status captives were used for labor.

The consumption of hallucinogenic plants as entheogens goes back to thousands of years. Psychoactive plants contain hallucinogenic particles that provoke an altered state of consciousness, which are known to have been used during spiritual rituals among cultures such as the Aztec, the Maya, and Inca. The Maya are indigenous people of Mexico and Central America that had significant access to hallucinogenic substances. Archaeological, ethnohistorical, and ethnographic data show that Mesoamerican cultures used psychedelic substances in therapeutic and religious rituals. The consumption of many of these substances dates back to the Olmec era ; however, Mayan religious texts reveal more information about the Aztec and Mayan civilization. These substances are considered entheogens because they were used to communicate with divine powers. "Entheogen," an alternative term for hallucinogen or psychedelic drug, derived from ancient Greek words ἔνθεος and γενέσθαι. This neologism was coined in 1979 by a group of ethnobotanists and scholars of mythology. Some authors claim entheogens have been used by priests throughout history, with appearances in prehistoric cave art such as a cave painting at Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria that dates to roughly 8000 BP. Shamans in Mesoamerica served to diagnose the cause of illness by seeking wisdom through a transformational experience by consuming drugs to learn the crisis of the illness