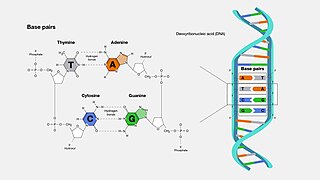

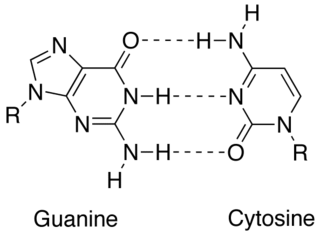

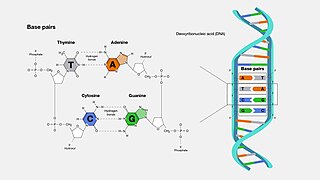

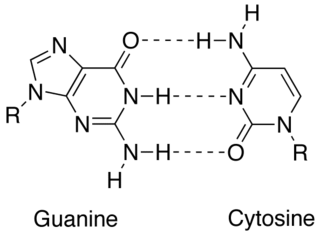

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA and RNA. Dictated by specific hydrogen bonding patterns, "Watson–Crick" base pairs allow the DNA helix to maintain a regular helical structure that is subtly dependent on its nucleotide sequence. The complementary nature of this based-paired structure provides a redundant copy of the genetic information encoded within each strand of DNA. The regular structure and data redundancy provided by the DNA double helix make DNA well suited to the storage of genetic information, while base-pairing between DNA and incoming nucleotides provides the mechanism through which DNA polymerase replicates DNA and RNA polymerase transcribes DNA into RNA. Many DNA-binding proteins can recognize specific base-pairing patterns that identify particular regulatory regions of genes.

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of all known organisms and many viruses. DNA and ribonucleic acid (RNA) are nucleic acids. Alongside proteins, lipids and complex carbohydrates (polysaccharides), nucleic acids are one of the four major types of macromolecules that are essential for all known forms of life.

In biochemistry, denaturation is a process in which proteins or nucleic acids lose folded structure present in their native state due to various factors, including application of some external stress or compound, such as a strong acid or base, a concentrated inorganic salt, an organic solvent, agitation and radiation, or heat. If proteins in a living cell are denatured, this results in disruption of cell activity and possibly cell death. Protein denaturation is also a consequence of cell death. Denatured proteins can exhibit a wide range of characteristics, from conformational change and loss of solubility or dissociation of cofactors to aggregation due to the exposure of hydrophobic groups. The loss of solubility as a result of denaturation is called coagulation. Denatured proteins lose their 3D structure, and therefore, cannot function.

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part of biological inheritance. This is essential for cell division during growth and repair of damaged tissues, while it also ensures that each of the new cells receives its own copy of the DNA. The cell possesses the distinctive property of division, which makes replication of DNA essential.

DNA synthesis is the natural or artificial creation of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecules. DNA is a macromolecule made up of nucleotide units, which are linked by covalent bonds and hydrogen bonds, in a repeating structure. DNA synthesis occurs when these nucleotide units are joined to form DNA; this can occur artificially or naturally. Nucleotide units are made up of a nitrogenous base, pentose sugar (deoxyribose) and phosphate group. Each unit is joined when a covalent bond forms between its phosphate group and the pentose sugar of the next nucleotide, forming a sugar-phosphate backbone. DNA is a complementary, double stranded structure as specific base pairing occurs naturally when hydrogen bonds form between the nucleotide bases.

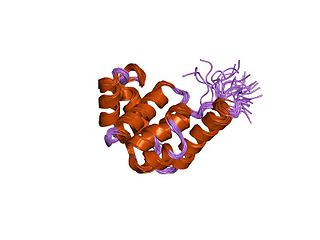

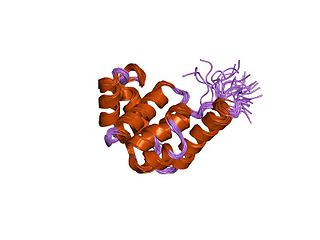

DnaB helicase is an enzyme in bacteria which opens the replication fork during DNA replication. Although the mechanism by which DnaB both couples ATP hydrolysis to translocation along DNA and denatures the duplex is unknown, a change in the quaternary structure of the protein involving dimerisation of the N-terminal domain has been observed and may occur during the enzymatic cycle. Initially when DnaB binds to dnaA, it is associated with dnaC, a negative regulator. After DnaC dissociates, DnaB binds dnaG.

Temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TGGE) and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) are forms of electrophoresis which use either a temperature or chemical gradient to denature the sample as it moves across an acrylamide gel. TGGE and DGGE can be applied to nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA, and proteins. TGGE relies on temperature dependent changes in structure to separate nucleic acids. DGGE separates genes of the same size based on their different denaturing ability which is determined by their base pair sequence. DGGE was the original technique, and TGGE a refinement of it.

In molecular biology, the term double helix refers to the structure formed by double-stranded molecules of nucleic acids such as DNA. The double helical structure of a nucleic acid complex arises as a consequence of its secondary structure, and is a fundamental component in determining its tertiary structure. The structure was discovered by Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin, her student Raymond Gosling, James Watson, and Francis Crick, while the term "double helix" entered popular culture with the 1968 publication of Watson's The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA.

Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is RNA with two complementary strands found in cells. It is similar to DNA but with the replacement of thymine by uracil and the adding of one oxygen atom. Despite the structural similarities, much less is known about dsRNA.

DNA supercoiling refers to the amount of twist in a particular DNA strand, which determines the amount of strain on it. A given strand may be "positively supercoiled" or "negatively supercoiled". The amount of a strand's supercoiling affects a number of biological processes, such as compacting DNA and regulating access to the genetic code. Certain enzymes, such as topoisomerases, change the amount of DNA supercoiling to facilitate functions such as DNA replication and transcription. The amount of supercoiling in a given strand is described by a mathematical formula that compares it to a reference state known as "relaxed B-form" DNA.

Protein metabolism denotes the various biochemical processes responsible for the synthesis of proteins and amino acids (anabolism), and the breakdown of proteins by catabolism.

Pyrimidine dimers represent molecular lesions originating from thymine or cytosine bases within DNA, resulting from photochemical reactions. These lesions, commonly linked to direct DNA damage, are induced by ultraviolet light (UV), particularly UVC, result in the formation of covalent bonds between adjacent nitrogenous bases along the nucleotide chain near their carbon–carbon double bonds, the photo-coupled dimers are fluorescent. Such dimerization, which can also occur in double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) involving uracil or cytosine, leads to the creation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and 6–4 photoproducts. These pre-mutagenic lesions modify the DNA helix structure, resulting in abnormal non-canonical base pairing and, consequently, adjacent thymines or cytosines in DNA will form a cyclobutane ring when joined together and cause a distortion in the DNA. This distortion prevents DNA replication and transcription mechanisms beyond the dimerization site.

SNP genotyping is the measurement of genetic variations of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between members of a species. It is a form of genotyping, which is the measurement of more general genetic variation. SNPs are one of the most common types of genetic variation. An SNP is a single base pair mutation at a specific locus, usually consisting of two alleles. SNPs are found to be involved in the etiology of many human diseases and are becoming of particular interest in pharmacogenetics. Because SNPs are conserved during evolution, they have been proposed as markers for use in quantitative trait loci (QTL) analysis and in association studies in place of microsatellites. The use of SNPs is being extended in the HapMap project, which aims to provide the minimal set of SNPs needed to genotype the human genome. SNPs can also provide a genetic fingerprint for use in identity testing. The increase of interest in SNPs has been reflected by the furious development of a diverse range of SNP genotyping methods.

Nucleic acid thermodynamics is the study of how temperature affects the nucleic acid structure of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). The melting temperature (Tm) is defined as the temperature at which half of the DNA strands are in the random coil or single-stranded (ssDNA) state. Tm depends on the length of the DNA molecule and its specific nucleotide sequence. DNA, when in a state where its two strands are dissociated, is referred to as having been denatured by the high temperature.

Melting curve analysis is an assessment of the dissociation characteristics of double-stranded DNA during heating. As the temperature is raised, the double strand begins to dissociate leading to a rise in the absorbance intensity, hyperchromicity. The temperature at which 50% of DNA is denatured is known as the melting temperature. Measurement of melting temperature can help us predict species by just studying the melting temperature. This is because every organism has a specific melting curve.

Nucleic acid structure refers to the structure of nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA. Chemically speaking, DNA and RNA are very similar. Nucleic acid structure is often divided into four different levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary.

Nucleic acid secondary structure is the basepairing interactions within a single nucleic acid polymer or between two polymers. It can be represented as a list of bases which are paired in a nucleic acid molecule. The secondary structures of biological DNAs and RNAs tend to be different: biological DNA mostly exists as fully base paired double helices, while biological RNA is single stranded and often forms complex and intricate base-pairing interactions due to its increased ability to form hydrogen bonds stemming from the extra hydroxyl group in the ribose sugar.

In molecular biology, complementarity describes a relationship between two structures each following the lock-and-key principle. In nature complementarity is the base principle of DNA replication and transcription as it is a property shared between two DNA or RNA sequences, such that when they are aligned antiparallel to each other, the nucleotide bases at each position in the sequences will be complementary, much like looking in the mirror and seeing the reverse of things. This complementary base pairing allows cells to copy information from one generation to another and even find and repair damage to the information stored in the sequences.

In the fields of geometry and biochemistry, a triple helix is a set of three congruent geometrical helices with the same axis, differing by a translation along the axis. This means that each of the helices keeps the same distance from the central axis. As with a single helix, a triple helix may be characterized by its pitch, diameter, and handedness. Examples of triple helices include triplex DNA, triplex RNA, the collagen helix, and collagen-like proteins.

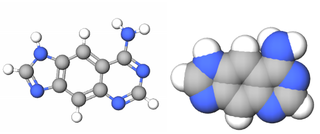

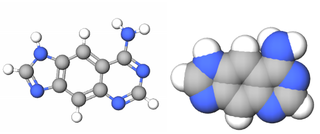

xDNA is a size-expanded nucleotide system synthesized from the fusion of a benzene ring and one of the four natural bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. This size expansion produces an 8 letter alphabet which has a larger information storage capacity than natural DNA's 4 letter alphabet. As with normal base-pairing, A pairs with xT, C pairs with xG, G pairs with xC, and T pairs with xA. The double helix is thus 2.4Å wider than a natural double helix. While similar in structure to B-DNA, xDNA has unique absorption, fluorescence, and stacking properties.