A furnace, referred to as a heater or boiler in British English, is an appliance used to generate heat for all or part of a building. Furnaces are mostly used as a major component of a central heating system. Furnaces are permanently installed to provide heat to an interior space through intermediary fluid movement, which may be air, steam, or hot water. Heating appliances that use steam or hot water as the fluid are normally referred to as a residential steam boilers or residential hot water boilers. The most common fuel source for modern furnaces in North America and much of Europe is natural gas; other common fuel sources include LPG, fuel oil, wood and in rare cases coal. In some areas electrical resistance heating is used, especially where the cost of electricity is low or the primary purpose is for air conditioning. Modern high-efficiency furnaces can be up to 98% efficient and operate without a chimney, with a typical gas furnace being about 80% efficient. Waste gas and heat are mechanically ventilated through either metal flue pipes or polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipes that can be vented through the side or roof of the structure. Fuel efficiency in a gas furnace is measured in AFUE.

In ancient Rome, thermae and balneae were facilities for bathing. Thermae usually refers to the large imperial bath complexes, while balneae were smaller-scale facilities, public or private, that existed in great numbers throughout Rome.

A central heating system provides warmth to a number of spaces within a building from one main source of heat. It is a component of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems, which can both cool and warm interior spaces.

The concept of home improvement, home renovation or remodeling is the process of renovating, making improvements or making additions to one's home. Home improvement can consist of projects that upgrade an existing home interior, exterior or other improvements to the property. Home improvement projects can be carried out for a number of different reasons; personal preference and comfort, maintenance or repair work, making a home bigger by adding rooms/spaces, as a means of saving energy, or to improve safety.

Ondol or gudeul in Korean traditional architecture is underfloor heating that uses direct heat transfer from wood smoke to heat the underside of a thick masonry floor. In modern usage, it refers to any type of underfloor heating, or to a hotel or a sleeping room in Korean style.

The kang is a traditional heated platform, 2 metres or more long, used for general living, working, entertaining and sleeping in the northern part of China, where the winter climate is cold. It is made of bricks or other forms of fired clay and more recently of concrete in some locations. The word kang means "to dry".

The tepidarium was the warm (tepidus) bathroom of the Roman baths heated by a hypocaust or underfloor heating system. The speciality of a tepidarium is the pleasant feeling of constant radiant heat, which directly affects the human body from the walls and floor.

A caldarium was a room with a hot plunge bath, used in a Roman bath complex. The boiler supplying hot water to a baths complex was also called caldarium.

A masonry heater is a device for warming an interior space through radiant heating, by capturing the heat from periodic burning of fuel, and then radiating the heat at a fairly constant temperature for a long period. Masonry heaters covered in tile are called Kachelofen. The technology has existed in different forms, from back into the Neoglacial and Neolithic periods. Archaeological digs have revealed excavations of ancient inhabitants utilizing hot smoke from fires in their subterranean dwellings, to radiate into the living spaces. These early forms eventually evolved into modern systems.

Gaius Sergius Orata was an Ancient Roman who was a successful merchant, inventor and hydraulic engineer. He is credited with inventing the cultivation of oysters and refinement to the hypocaust method of heating a building to provide, in addition, heated water for bathing.

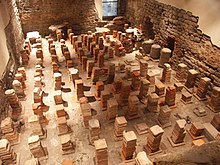

Pilae stacks are stacks of pilae tiles, square or round tiles, that were used in Roman times as an element of the underfloor heating system, common in Roman bathhouses, called the hypocaust. The concept of the pilae stacks is that the floor is constructed at an elevated position, allowing air to freely circulate underneath and up, through the hollow bricks, into the structure walls. Examples of such baths are found not only in Rome, but also in distant parts of the Roman Empire such as Roman Britain, or Chellah, in modern-day Morocco.

Borough Hill Roman villa is located on the north tip of Borough Hill, a prominent hill near the town of Daventry in Northamptonshire. The villa’s remains lie within the ramparts of an Iron Age fortress which covers the summit of the hill. The remains of the Roman villa were discovered in 1823 by the historian and archaeologist George Baker, who identified Borough Hill with the Benaventa of the Britons and Isannavaria of the Romans. The remains were not fully excavated until 1852 when local historian Beriah Botfield thoroughly excavated and recorded the site. Botfield employed an artist to make drawings of the site and these illustrations along with Botfield's notes, manuscripts and some of the antiquities found on the site are now kept at the British Museum.

Gloria is a central heating system used in Castile, beginning in the Middle Ages. It is a direct descendant of the Roman hypocaust, and due to its slow rate of combustion, it allows people to use smaller, cheaper fuels, such as leaves, hay, or twigs, instead of wood.

The Roman Baths of Ankara are the ruined remains of an ancient Roman bath complex in Ankara, Turkey, which were uncovered by excavations carried out in 1937–1944, and have subsequently been opened to the public as an open-air museum.

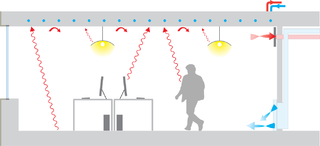

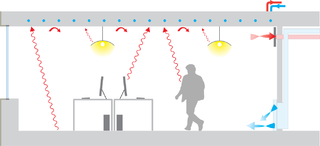

Radiant heating and cooling is a category of HVAC technologies that exchange heat by both convection and radiation with the environments they are designed to heat or cool. There are many subcategories of radiant heating and cooling, including: "radiant ceiling panels", "embedded surface systems", "thermally active building systems", and infrared heaters. According to some definitions, a technology is only included in this category if radiation comprises more than 50% of its heat exchange with the environment; therefore technologies such as radiators and chilled beams are usually not considered radiant heating or cooling. Within this category, it is practical to distinguish between high temperature radiant heating, and radiant heating or cooling with more moderate source temperatures. This article mainly addresses radiant heating and cooling with moderate source temperatures, used to heat or cool indoor environments. Moderate temperature radiant heating and cooling is usually composed of relatively large surfaces that are internally heated or cooled using hydronic or electrical sources. For high temperature indoor or outdoor radiant heating, see: Infrared heater. For snow melt applications see: Snowmelt system.

Nabatean architecture refers to the building traditions of the Nabateans, an ancient Arab people who inhabited northern Arabia and the southern Levant. Their settlements—most prominently the assumed capital city of Raqmu —gave the name Nabatene to the Arabian borderland that stretched from the Euphrates to the Red Sea. Their architectural style is notable for its temples and tombs, most famously the ones found in Petra. The style appears to be a mix of Mesopotamian, Phoenician, Hellenisticn, and South Arabian influences modified to suit the Arab architectural taste. Petra, the capital of the kingdom of Nabatea, is as famous now as it was in the antiquity for its remarkable rock-cut tombs and temples. Most architectural Nabatean remains, dating from the 1st century BC to the 2nd century AD, are highly visible and well-preserved, with over 500 monuments in Petra, in modern-day Jordan, and 110 well preserved tombs set in the desert landscape of Hegra, now in modern-day Saudi Arabia. Much of the surviving architecture was carved out of rock cliffs, hence the columns do not actually support anything but are used for purely ornamental purposes. In addition to the most famous sites in Petra, there are also Nabatean complexes at Obodas (Avdat) and residential complexes at Mampsis (Kurnub) and a religious site of et-Tannur.

The Roman Berytus are located in the middle of downtown Beirut, Lebanon between Banks Street and Capuchin Street. The remains of a Roman bath of Berytus now surrounded by government buildings were found and conserved for posterity.

The Carsington Roman Villa is a Roman villa at Scow Brook, Carsington near Wirksworth, Derbyshire, England.

The Stabian Baths are an ancient Roman bathing complex in Pompeii, Italy, the oldest and the largest of the 5 public baths in the city. Their original construction dates back to ca. 125 BC, making them one of the oldest bathing complexes known from the ancient world. They were remodelled and enlarged many times up to the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD.

In Ancient Rome, the praefurnium designated the room and the furnace that ensured the heating of the hot or warm premises of the thermae.