Related Research Articles

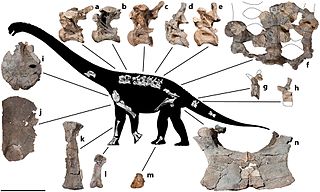

Argentinosaurus is a genus of giant sauropod dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period in what is now Argentina. Although it is only known from fragmentary remains, Argentinosaurus is one of the largest known land animals of all time, perhaps the largest, measuring 30–35 metres (98–115 ft) long and weighing 65–80 tonnes. It was a member of Titanosauria, the dominant group of sauropods during the Cretaceous. It is widely regarded by many paleontologists as the biggest dinosaur ever, and perhaps lengthwise the longest animal ever, though both claims have no concrete evidence yet.

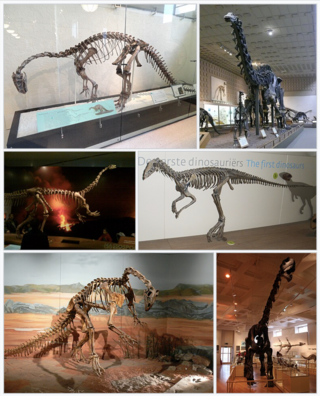

Sauropodomorpha is an extinct clade of long-necked, herbivorous, saurischian dinosaurs that includes the sauropods and their ancestral relatives. Sauropods generally grew to very large sizes, had long necks and tails, were quadrupedal, and became the largest animals to ever walk the Earth. The prosauropods, which preceded the sauropods, were smaller and were often able to walk on two legs. The sauropodomorphs were the dominant terrestrial herbivores throughout much of the Mesozoic Era, from their origins in the Late Triassic until their decline and extinction at the end of the Cretaceous.

Barapasaurus is a genus of basal sauropod dinosaur from Jurassic rocks of India. The only species is B. tagorei. Barapasaurus comes from the lower part of the Kota Formation, which is of Early to Middle Jurassic age. It is therefore one of the earliest known sauropods. Barapasaurus is known from approximately 300 bones from at least six individuals, so that the skeleton is almost completely known except for the anterior cervical vertebrae and the skull. This makes Barapasaurus one of the most completely known sauropods from the early Jurassic.

Titanosaurs were a diverse group of sauropod dinosaurs, including genera from all seven continents. The titanosaurs were the last surviving group of long-necked sauropods, with taxa still thriving at the time of the extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous. This group includes some of the largest land animals known to have ever existed, such as Patagotitan, estimated at 37 m (121 ft) long with a weight of 69 tonnes, and the comparably-sized Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus from the same region.

Archosauromorpha is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs rather than Pantestudines. Archosauromorphs first appeared during the late Middle Permian or Late Permian, though they became much more common and diverse during the Triassic period.

Cetiosaurus meaning 'whale lizard', from the Greek keteios/κήτειος meaning 'sea monster' and sauros/σαυρος meaning 'lizard', is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic Period, living about 168 million years ago in what is now Britain.

Opisthocoelicaudia is a genus of sauropod dinosaur of the Late Cretaceous Period discovered in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. The type species is Opisthocoelicaudia skarzynskii. A well-preserved skeleton lacking only the head and neck was unearthed in 1965 by Polish and Mongolian scientists, making Opisthocoelicaudia one of the best known sauropods from the Late Cretaceous. Tooth marks on this skeleton indicate that large carnivorous dinosaurs had fed on the carcass and possibly had carried away the now-missing parts. To date, only two additional, much less complete specimens are known, including part of a shoulder and a fragmentary tail. A relatively small sauropod, Opisthocoelicaudia measured about 11.4–13 m (37–43 ft) in length. Like other sauropods, it would have been characterised by a small head sitting on a very long neck and a barrel shaped trunk carried by four column-like legs. The name Opisthocoelicaudia means "posterior cavity tail", alluding to the unusual, opisthocoel condition of the anterior tail vertebrae that were concave on their posterior sides. This and other skeletal features lead researchers to propose that Opisthocoelicaudia was able to rear on its hindlegs.

Andesaurus is a genus of basal titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur which existed during the middle of the Cretaceous Period in South America. Like most sauropods, belonging to one of the largest animals ever to walk the Earth, it would have had a small head on the end of a long neck and an equally long tail.

Histriasaurus (HIS-tree-ah-SAWR-us) was a genus of dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous. Its fossils, holotype WN V-6, were found in a bonebed in lacustrine limestone exposed on the seafloor off the coast of the town of Bale on the Istrian peninsula in Croatia by Dario Boscarolli during the 1980s, and described in 1998 by Dalla Vecchia. It was a diplodocoid sauropod, related to, but more primitive than, Rebbachisaurus. Phylogenetic analyses published in 2007 and 2011 placed Histriasaurus as the most basal member of Rebbachisauridae.

Puertasaurus is a genus of sauropod dinosaur that lived in South America during the Late Cretaceous Period. It is known from a single specimen recovered from sedimentary rocks of the Cerro Fortaleza Formation in southwestern Patagonia, Argentina, which probably is Campanian or Maastrichtian in age. The only species is Puertasaurus reuili. Described by the paleontologist Fernando Novas and colleagues in 2005, it was named in honor of Pablo Puerta and Santiago Reuil, who discovered and prepared the specimen. It consists of four well-preserved vertebrae, including one cervical, one dorsal, and two caudal vertebrae. Puertasaurus is a member of Titanosauria, the dominant group of sauropods during the Cretaceous.

Nanshiungosaurus is a genus of therizinosaurid that lived in what is now Asia during the Late Cretaceous of South China. The type species, Nanshiungosaurus brevispinus, was first discovered in 1974 and described in 1979 by Dong Zhiming. It is represented by a single specimen preserving most of the cervical and dorsal vertebrae with the pelvis. A supposed and unlikely second species, "Nanshiungosaurus" bohlini, was found in 1992 and described in 1997. It is also represented by vertebrae but this species however, differs in geological age and lacks authentic characteristics compared to the type, making its affinity to the genus unsupported.

Saurischia is one of the two basic divisions of dinosaurs, classified by their hip structure. Saurischia and Ornithischia were originally called orders by Harry Seeley in 1888 though today most paleontologists classify Saurischia as an unranked clade rather than an order.

Fasolasuchus is an extinct genus of loricatan. Fossils have been found in the Los Colorados Formation of the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin in northwestern Argentina that date back to the Norian stage of the Late Triassic, making it one of the last "rauisuchians" to have existed before the order became extinct at the end of the Triassic.

Spinophorosaurus is a genus of sauropod dinosaur that lived in what is now Niger during the Middle Jurassic period. The first two specimens were excavated in the 2000s by German and Spanish teams under difficult conditions. The skeletons were brought to Europe and digitally replicated, making Spinophorosaurus the first sauropod to have its skeleton 3D printed, and were to be returned to Niger in the future. Together, the two specimens represented most of the skeleton of the genus, and one of the most completely known basal sauropods of its time and place. The first skeleton was made the holotype specimen of the new genus and species Spinophorosaurus nigerensis in 2009; the generic name refers to what was initially thought to be spiked osteoderms, and the specific name refers to where it was found. A juvenile sauropod from the same area was later assigned to the genus.

The zygosphene-zygantrum articulation is an accessory joint between vertebrae found in several lepidosauromorph reptiles. This pivot joint consists of a forward-facing, wedge-shaped process called the zygosphene, that fits in a depression on the rearside of the next vertebrae, called the zygantrum. The zygosphene sits between the prezygapophysis in the neural arch, whereas the zygantrum sits between the postzygapophysis.

Epipophyses are bony projections of the cervical vertebrae found in archosauromorphs, particularly dinosaurs. These paired processes sit above the postzygapophyses on the rear of the vertebral neural arch. Their morphology is variable and ranges from small, simple, hill-like elevations to large, complex, winglike projections. Epipophyses provided large attachment areas for several neck muscles; large epipophyses are therefore indicative of a strong neck musculature.

This glossary explains technical terms commonly employed in the description of dinosaur body fossils. Besides dinosaur-specific terms, it covers terms with wider usage, when these are of central importance in the study of dinosaurs or when their discussion in the context of dinosaurs is beneficial. The glossary does not cover ichnological and bone histological terms, nor does it cover measurements.

Patagotitan is a genus of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur from the Cerro Barcino Formation in Chubut Province, Patagonia, Argentina. The genus contains a single species known from at least six young adult individuals, Patagotitan mayorum, which was first announced in 2014 and then named in 2017 by José Carballido and colleagues. Preliminary studies and press releases suggested that Patagotitan was the largest known titanosaur and land animal overall, with an estimated length of 37 m (121 ft) and an estimated weight of 69 tonnes. Later research revised the length estimate down to 31 m (102 ft) and weight estimates down to approximately 50–57 tonnes, suggesting that Patagotitan was of a similar size to, if not smaller than, its closest relatives Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus. Still, Patagotitan is one of the most-known titanosaurs, and so its interrelationships with other titanosaurs have been relatively consistent in phylogenetic analyses. This led to its use in a re-definition of the group Colossosauria by Carballido and colleagues in 2022.

Austroposeidon is a genus of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Presidente Prudente Formation of Brazil. It contains one species, Austroposeidon magnificus.

Savannasaurus is a genus of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Winton Formation of Queensland, Australia. It contains one species, Savannasaurus elliottorum, named in 2016 by Stephen Poropat and colleagues. The holotype and only known specimen, originally nicknamed "Wade", is the most complete specimen of an Australian sauropod, and is held at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs museum. Dinosaurs known from contemporary rocks include its close relative Diamantinasaurus and the theropod Australovenator; associated teeth suggest that Australovenator may have fed on the holotype specimen.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Apesteguía, Sebastián (2005). "Evolution of the Hyposphene-Hypantrum Complex within Sauropoda". In Virginia Tidwell; Kenneth Carpenter (eds.). Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34542-4.

- ↑ Piechowski, Rafal; Jerzy Dzik (2010). "The axial skeleton of Silesaurus opolensis". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (4): 1127–1141. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.483547. S2CID 86296113.

- 1 2 3 Rauhut, Oliver W.M. (2003). The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs. Special Papers in Palaeontology. Vol. 69. pp. 1–213. ISBN 978-0-901702-79-1.

- 1 2 Gauthier, Jacques (1986). "Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds". Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences. 8 (1): 16–17.

- ↑ Langer, Max C. (2004). "Basal Saurischia" (PDF). In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-07. Retrieved 2012-12-14.