Squamata is the largest order of reptiles, comprising lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians, which are collectively known as squamates or scaled reptiles. With over 10,000 species, it is also the second-largest order of extant (living) vertebrates, after the perciform fish, and roughly equal in number to the Saurischia. Members of the order are distinguished by their skins, which bear horny scales or shields. They also possess movable quadrate bones, making it possible to move the upper jaw relative to the neurocranium. This is particularly visible in snakes, which are able to open their mouths very wide to accommodate comparatively large prey. Squamata is the most variably sized order of reptiles, ranging from the 16 mm (0.63 in) dwarf gecko to the 5.21 m (17.1 ft) green anaconda and the now-extinct mosasaurs, which reached lengths of over 14 m (46 ft).

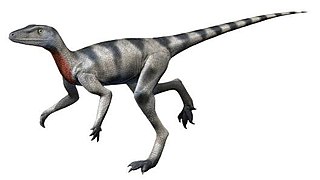

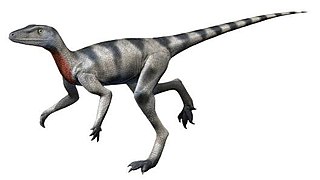

Saltopus is a genus of very small bipedal dinosauriform containing the single species S. elginensis from the late Triassic period of Scotland. It is one of the most famous Elgin Reptiles.

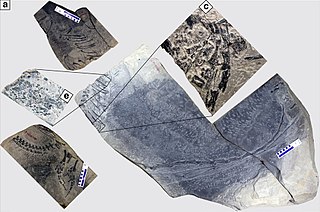

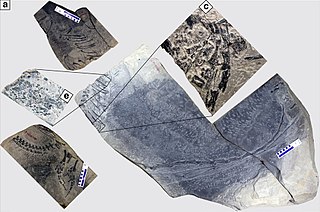

Dinocephalosaurus is a genus of long necked, aquatic protorosaur that inhabited the Triassic seas of China. The genus contains the type and only known species, D. orientalis, which was named by Li in 2003. Unlike other long-necked protorosaurs, Dinocephalosaurus convergently evolved a long neck not through elongation of individual cervical vertebrae, but through the addition of cervical vertebrae that each have a moderate length. Like other tanystropheids, however, Dinocephalosaurus probably used its long neck to hunt for prey, utilizing a combination of suction, created by the expansion of the throat, and the fang-like teeth of the jaws to ensnare prey. It was probably a marine animal by necessity, as suggested by the poorly-ossified and paddle-like limbs which would have prevented it from going ashore.

Labyrinthodontia is an extinct amphibian subclass, which constituted some of the dominant animals of late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. The group evolved from lobe-finned fishes in the Devonian and is ancestral to all extant landliving vertebrates. As such it constitutes an evolutionary grade rather than a natural group (clade). The name describes the pattern of infolding of the dentin and enamel of the teeth, which are often the only part of the creatures that fossilize. They are also distinguished by a heavily armoured skull roof, and complex vertebrae, the structure of which were used in older classifications of the group.

Cetiosauriscus is a genus of sauropod dinosaur that lived between 166 and 164 million years ago during the Callovian in what is now England. A herbivore, Cetiosauriscus had—for sauropod standards—a moderately long tail, and longer forelimbs, making them as long as its hindlimbs. It has been estimated as about 15 m (49 ft) long and between 4 and 10 t in weight.

Petrolacosaurus was an extinct genus of diapsid reptile from the late Carboniferous period. It was a small, 40-centimetre (16 in) long reptile, and the earliest known reptile with two temporal fenestrae. This means that it was at the base of Diapsida, the largest and most successful radiation of reptiles that would eventually include all modern reptile groups, as well as dinosaurs and other famous extinct reptiles such as plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and pterosaurs. However, Petrolacosaurus itself was part of Araeoscelida, a short-lived early branch of the diapsid family tree which went extinct in the mid-Permian.

Ticinosuchus is an extinct genus of pseudosuchian archosaur from the Middle Triassic of Switzerland and Italy.

Utatsusaurus hataii is the earliest-known ichthyopterygian which lived in the early Triassic period. It is nearly 3 m long with a slender body. The first specimen was found in Utatsu-cho, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan. It is the only described species in the genus Utatsusaurus and the only member of the family Utatsusauridae. The name Utatsusaurus was given after the city. The fossils have been found from the Lower Triassic of Miyagi Prefecture, Japan and British Columbia, Canada.

Ctenosauriscus is an extinct genus of sail-backed poposauroid archosaur from Early Triassic deposits of Lower Saxony in northern Germany. It gives its name to the family Ctenosauriscidae, which includes other sail-backed poposauroids such as Arizonasaurus. Fossils have been found in latest Olenekian deposits around 247.5-247.2 million years old, making it one of the first known archosaurs.

Eunotosaurus is an extinct genus of reptile, possibly a close relative of turtles, from the late Middle Permian Karoo Supergroup of South Africa. It is often considered as a possible "missing link" between turtles and their prehistoric ancestors. Its ribs were wide and flat, forming broad plates similar to a primitive turtle shell, and the vertebrae were nearly identical to those of some turtles. It is possible that these turtle-like features evolved independently of the same features in turtles, though some studies suggest Eunotosaurus is a genuine, primitive turtle relative. Other anatomical studies and phylogenetic analysis suggest that Eunotosaurus is a parareptile and not a basal turtle.

Fasolasuchus is an extinct genus of rauisuchid. Fossils have been found in the Los Colorados Formation of Argentina that date back to the Rhaetian stage of the Late Triassic, making it one of the last rauisuchians to have existed before the order became extinct at the end of the Triassic.

Sanjuansaurus is a genus of herrerasaurid dinosaur from the Late Triassic-age Ischigualasto Formation of northwestern Argentina.

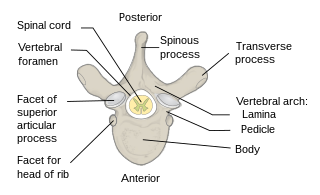

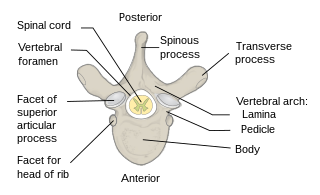

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord found in all chordates has been replaced by a segmented series of bone: vertebrae separated by intervertebral discs. The vertebral column houses the spinal canal, a cavity that encloses and protects the spinal cord.

Dahalokely is an extinct genus of carnivorous abelisauroid theropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous (Turonian) of Madagascar.

Pamelaria is an extinct genus of allokotosaurian archosauromorph reptile known from a single species, Pamelaria dolichotrachela, from the Middle Triassic of India. Pamelaria has sprawling legs, a long neck, and a pointed skull with nostrils positioned at the very tip of the snout. Among early archosauromorphs, Pamelaria is most similar to Prolacerta from the Early Triassic of South Africa and Antarctica. Both have been placed in the family Prolacertidae. Pamelaria, Prolacerta, and various other Permo-Triassic reptiles such as Protorosaurus and Tanystropheus have often been placed in a group of archosauromorphs called Protorosauria, which was regarded as one of the most basal group of archosauromorphs. However, more recent phylogenetic analyses indicate that Pamelaria and Prolacerta are more closely related to Archosauriformes than are Protorosaurus, Tanystropheus, and other protorosaurs, making Protorosauria a polyphyletic grouping.

This glossary explains technical terms commonly employed in the description of dinosaur body fossils. Besides dinosaur-specific terms, it covers terms with wider usage, when these are of central importance in the study of dinosaurs or when their discussion in the context of dinosaurs is beneficial. The glossary does not cover ichnological and bone histological terms, nor does it cover measurements.

In the vertebrate spinal column, each vertebra is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, the proportions of which vary according to the segment of the backbone and the species of vertebrate.

Kevin de Queiroz is a vertebrate, evolutionary, and systematic biologist. He has worked in the phylogenetics and evolutionary biology of squamate reptiles, the development of a unified species concept and of a phylogenetic approach to biological nomenclature, and the philosophy of systematic biology.