The Arapaho are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

Kiowa or Ka'igwa people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries, and eventually into the Southern Plains by the early 19th century. In 1867, the Kiowa were moved to a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma.

Quanah Parker was a war leader of the Kwahadi ("Antelope") band of the Comanche Nation. He was likely born into the Nokoni ("Wanderers") band of Tabby-nocca and grew up among the Kwahadis, the son of Kwahadi Comanche chief Peta Nocona and Cynthia Ann Parker, an Anglo-American who had been abducted as an eight-year-old child and assimilated into the Nokoni tribe. Following the apprehension of several Kiowa chiefs in 1871, Quanah Parker emerged as a dominant figure in the Red River War, clashing repeatedly with Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie. With European-Americans hunting American bison, the Comanches' primary sustenance, into near extinction, Quanah Parker eventually surrendered and peaceably led the Kwahadi to the reservation at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

Black Kettle was a prominent leader of the Southern Cheyenne during the American Indian Wars. Born to the Northern Só'taeo'o / Só'taétaneo'o band of the Northern Cheyenne in the Black Hills of present-day South Dakota, he later married into the Wotápio / Wutapai band of the Southern Cheyenne.

The Medicine Lodge Treaty is the overall name for three treaties signed near Medicine Lodge, Kansas, between the Federal government of the United States and southern Plains Indian tribes in October 1867, intended to bring peace to the area by relocating the Native Americans to reservations in Indian Territory and away from European-American settlement. The treaty was negotiated after investigation by the Indian Peace Commission, which in its final report in 1868 concluded that the wars had been preventable. They determined that the United States government and its representatives, including the United States Congress, had contributed to the warfare on the Great Plains by failing to fulfill their legal obligations and to treat the Native Americans with honesty.

The Red River War was a military campaign launched by the United States Army in 1874 to displace the Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho Native American tribes from the Southern Plains, and forcibly relocate the tribes to reservations in Indian Territory. The war had several army columns crisscross the Texas Panhandle in an effort to locate, harass, and capture nomadic Native American bands. Most of the engagements were small skirmishes with few casualties on either side. The war wound down over the last few months of 1874, as fewer and fewer Indian bands had the strength and supplies to remain in the field. Though the last significantly sized group did not surrender until mid-1875, the war marked the end of free-roaming Indian populations on the southern Great Plains.

Fort Sill is a United States Army post north of Lawton, Oklahoma, about 85 miles (137 km) southwest of Oklahoma City. It covers almost 94,000 acres (38,000 ha).

The Plains Apache are a small Southern Athabaskan group who live on the Southern Plains of North America, in close association with the linguistically unrelated Kiowa Tribe. Today, they are centered in Southwestern Oklahoma and Northern Texas and are federally recognized as the Apache Tribe of Oklahoma.

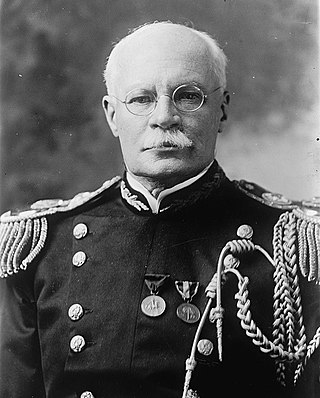

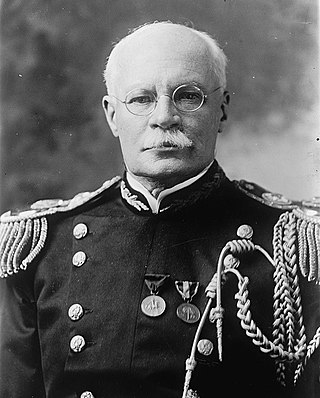

Major General Hugh Lenox Scott was a United States Army officer. A West Point graduate of 1876, he served as superintendent of West Point from 1906 to 1910 and as chief of staff of the United States Army from 1914 to 1917, which included the first few months of American involvement in World War I.

Comanche history is the story of the Native American (Indian) tribe which lived on the Great Plains of the present-day United States. In the 17th century the Eastern Shoshone people who became known as the Comanche migrated southward from Wyoming. In the 18th and 19th centuries the Comanche became the dominant tribe on the southern Great Plains. The Comanche are often characterized as "Lords of the Plains." They presided over a large area called Comancheria which they shared with allied tribes, the Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, Wichita, and after 1840 the southern Cheyenne and Arapaho. Comanche power and their substantial wealth depended on horses, trading, and raiding. Adroit diplomacy was also a factor in maintaining their dominance and fending off enemies for more than a century. They subsisted on the bison herds of the Plains which they hunted for food and skins.

The Battle of Palo Duro Canyon was a military confrontation and a significant United States victory during the Red River War. The battle occurred on September 28, 1874, when several U.S. Army companies under Ranald S. Mackenzie attacked a large encampment of Plains Indians in Palo Duro Canyon in the Texas Panhandle.

Native Americans have made up an integral part of U.S. military conflicts since America's beginning. Colonists recruited Indian allies during such instances as the Pequot War from 1634–1638, the Revolutionary War, as well as in War of 1812. Native Americans also fought on both sides during the American Civil War, as well as military missions abroad including the most notable, the Codetalkers who served in World War II. The Scouts were active in the American West in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Including those who accompanied General John J. Pershing in 1916 on his expedition to Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa. Indian Scouts were officially deactivated in 1947 when their last member retired from the Army at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. For many Indians it was an important form of interaction with European-American culture and their first major encounter with the Whites' way of thinking and doing things.

The Texas–Indian wars were a series of conflicts between settlers in Texas and the Southern Plains Indians during the 19th-century. Conflict between the Plains Indians and the Spanish began before other European and Anglo-American settlers were encouraged—first by Spain and then by the newly Independent Mexican government—to colonize Texas in order to provide a protective-settlement buffer in Texas between the Plains Indians and the rest of Mexico. As a consequence, conflict between Anglo-American settlers and Plains Indians occurred during the Texas colonial period as part of Mexico. The conflicts continued after Texas secured its independence from Mexico in 1836 and did not end until 30 years after Texas became a state of the United States, when in 1875 the last free band of Plains Indians, the Comanches led by Quahadi warrior Quanah Parker, surrendered and moved to the Fort Sill reservation in Oklahoma.

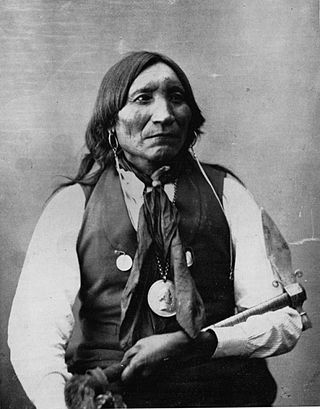

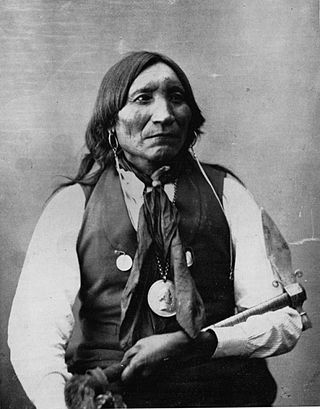

Dohäsan, Dohosan, Tauhawsin, Tohausen, or Touhason was a prominent Native American. He was War Chief of the Kata or Arikara band of the Kiowa Indians, and then Principal Chief of the entire Kiowa Tribe, a position he held for an extraordinary 33 years. He is best remembered as the last undisputed Principal Chief of the Kiowa people before the Reservation Era, and the battlefield leader of the Plains Tribes in the largest battle ever fought between the Plains tribes and the United States.

David Pendleton Oakerhater, also known as O-kuh-ha-tuh and Making Medicine, was a Cheyenne warrior and spiritual leader. He later became an artist and Episcopal deacon. In 1985, Oakerhater was the first Native American Anglican to be designated by the Episcopal Church as a saint.

The Indian Peace Commission was a group formed by an act of Congress on July 20, 1867 "to establish peace with certain hostile Indian tribes." It was composed of four civilians and three, later four, military leaders. Throughout 1867 and 1868, they negotiated with a number of tribes, including the Comanche, Kiowa, Arapaho, Kiowa-Apache, Cheyenne, Lakota, Navajo, Snake, Sioux, and Bannock. The treaties that resulted were designed to move the tribes to reservations, to "civilize" and assimilate these native peoples, and transition their societies from a nomadic to an agricultural existence.

Guipago or Lone Wolf [the Elder] was the last Principal Chief of the Kiowa tribe. He was a member of the Koitsenko, the Kiowa warrior elite, and was a signer of the Little Arkansas Treaty in 1865.

Little Raven, also known as Hosa, was from about 1855 until his death in 1889 a principal chief of the Southern Arapaho Indians. He negotiated peace between the Southern Arapaho and Cheyenne and the Comanche, Kiowa, and Plains Apache. He also secured rights to the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation in Indian Territory.

Big Red Meat was a Nokoni Comanche chief and a leader of Native American resistance against White invasion during the second half of the 19th century.

Blockhouse on Signal Mountain is located along Mackenzie Hill Road within the West Range of the Fort Sill Military Reservation inceptively declared as Camp Wichita during May 1868 within the current administrative division of Comanche County, Oklahoma. The blockhouse was established in 1871 pursuant to the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867.