Related Research Articles

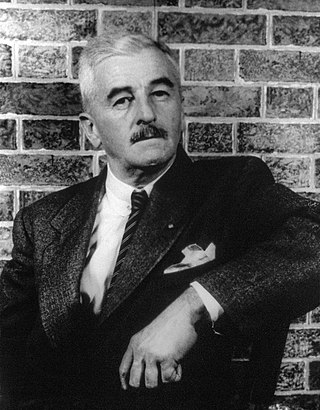

William Cuthbert Faulkner was an American writer. He is best known for his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, a stand-in for Lafayette County where he spent most of his life. A Nobel laureate, Faulkner is one of the most celebrated writers of American literature and often is considered the greatest writer of Southern literature.

Eudora Alice Welty was an American short story writer, novelist and photographer who wrote about the American South. Her novel The Optimist's Daughter won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973. Welty received numerous awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Order of the South. She was the first living author to have her works published by the Library of America. Her house in Jackson, Mississippi has been designated as a National Historic Landmark and is open to the public as a house museum.

Jamaica Kincaid is an Antiguan–American novelist, essayist, gardener, and gardening writer. Born in St. John's, the capital of Antigua and Barbuda, she now lives in North Bennington, Vermont, and is Professor of African and African American Studies in Residence, Emerita at Harvard University.

Monica Elizabeth Jolley AO was an English-born Australian writer who settled in Western Australia in the late 1950s and forged an illustrious literary career there. She was 53 when her first book was published, and she went on to publish fifteen novels, four short story collections and three non-fiction books, publishing well into her 70s and achieving significant critical acclaim. She was also a pioneer of creative writing teaching in Australia, counting many well-known writers such as Tim Winton among her students at Curtin University.

Peter De Vries was an American editor and novelist known for his satiric wit.

"A Rose for Emily" is a short story by American author William Faulkner, first published on April 30, 1930, in an issue of The Forum. The story takes place in Faulkner's fictional Jefferson, Mississippi, in the equally fictional county of Yoknapatawpha. It was Faulkner's first short story published in a national magazine.

Meridel Le Sueur was an American writer associated with the proletarian literature movement of the 1930s and 1940s. Born as Meridel Wharton, she assumed the name of her mother's second husband, Arthur Le Sueur, the former Socialist mayor of Minot, North Dakota.

Tillie Lerner Olsen was an American writer who was associated with the political turmoil of the 1930s and the first generation of American feminists.

Jayne Anne Phillips is an American Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and short story writer who was born in the small town of Buckhannon, West Virginia.

Elizabeth Strout is an American novelist and author. She is widely known for her works in literary fiction and her descriptive characterization. She was born and raised in Portland, Maine, and her experiences in her youth served as inspiration for her novels–the fictional "Shirley Falls, Maine" is the setting of four of her nine novels.

The Feminist Press at CUNY is an American independent nonprofit literary publisher of the City University of New York, based in New York City. It primarily publishes feminist literature that promotes freedom of expression and social justice.

Yonnondio: From the Thirties is a novel by American author Tillie Olsen which was published in 1974 but written in the 1930s. The novel details the lives of the Holbrook family, depicting their struggle to survive during the 1920s. Yonnondio explores the life of the working-class family, as well as themes of motherhood, socioeconomic order, and the pre-depression era. The novel was published as an unfinished work.

Tell Me a Riddle is a 1980 American drama film directed by actress Lee Grant. The screenplay by Joyce Eliason and Alev Lytle is based on the 1961 O. Henry Award novella from Tillie Olsen's collection of short stories of the same name. Tell Me a Riddle was Grant's first film as director. Grant and Eliason would later collaborate on David Lynch's Mulholland Drive.

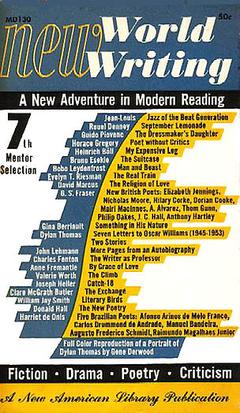

New World Writing was a paperback magazine, a literary anthology series published by New American Library's Mentor imprint from 1951 until 1960, then J. B. Lippincott & Co.'s Keystone from volume/issue 16 (1960) to the last volume, 22, in 1964.

Tillie Olsen: A Heart in Action is a 2007 documentary film directed and produced by Ann Hershey on the life and literary influence of Tillie Olsen, the U.S. writer best known for the books Tell Me a Riddle (1961) and Yonnondio: From the Thirties (1974). The film includes extensive interviews with Olsen and with prominent fans of her work, including writers Alice Walker and Florence Howe and feminist political leader Gloria Steinem.

Margaret Rose "Midge" MacKenzie, was a London-born writer and filmmaker who first become known for producing Robert Joffrey's multimedia ballet Astarte with the Joffrey Ballet, and Women Talking, a documentary with interviews of Kate Millett, Betty Friedan and other leading figures in the US women's liberation movement.

Jacqueline Jill Robinson is a Canadian writer and editor. She is the author of a novel and four collections of short stories. Her fiction and creative nonfiction have appeared in a wide variety of magazines and literary journals including Geist, the Antigonish Review, Event, Prairie Fire and the Windsor Review. Her novel, More In Anger, published in 2012, tells the stories of three generations of mothers and daughters who bear the emotional scars of loveless marriages, corrosive anger and misogyny.

Michelle Herman is an American writer and Professor Emerita of English at Ohio State University. Her most widely known work is the novel Dog, which WorldCat shows in 545 libraries and has been translated into multiple languages. She has also written the novel Missing, which was awarded the Harold Ribalow Prize for Jewish fiction, and Close-Up, which won the Donald L. Jordan Prize for Literary Excellence. She is married to Glen Holland, a still life painter. They have a daughter.

Tell Me a Riddle is a collection of short fiction by Tillie Olsen first published by J. B. Lippincott & Co. in 1961.

Joanne Schultz Frye is a Professor Emerita of English and Women's Studies at the College of Wooster. Frye is known for her feminist literary criticism and interdisciplinary inquiry into motherhood. She specializes in research on fiction by and about women, such as the work of Virginia Woolf, Tillie Olsen, and Jane Lazarre.

References

- ↑ Frye, 1995 p. 217-218: Selected Bibliography

- ↑ Pearlman and Werlock, 1991 p. 29-30

- ↑ Pearlman and Werlock, 1991 p. 6: "...anthologized more than 90 times..."

- ↑ Olsen, Tillie (1956). Tell me a riddle. New York: Dell. ISBN 978-0-440-38573-8. OCLC 748997729.

- ↑ Frye, 1995 p. 20

- ↑ Pearlman and Werlock, 1991 p. 30

- ↑ Mambrol,2020

- ↑ "She does not smile easily, let alone almost always as her brothers and sisters do."

- ↑ ""I Stand Here Ironing": Motherhood as Experience and Metaphor". login.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au. Archived from the original on 2014-11-17. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ↑ Mambrol, 2020: Plot summary

- ↑ Faulkner, 1993 pp. 116-119: Plot summary

- ↑ ""I Stand Here Ironing": Motherhood as Experience and Metaphor". login.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au. Archived from the original on 2014-11-17. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ↑ Pearlman and Werlock, 1991 p. 28: Foff "had nothing more to teach her..." And: Olsen: "I loved [Foff], and am deeply indebted to him..."

- ↑ Pearlman and Werlock, 1991 p. 121

- ↑ Pearlman and Werlock, 1991 p. 121

- ↑ Pearlman and Werlock, 1991 p. 29-30

- ↑ "Important Quotes Explained". Sparknotes. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ↑ Frye, 1995 p. 21: Ellipsis in original by Frye, interview with Olsen And p. 32: See section on Metaphor and Metonymy

- ↑ Frye, 1995 p. 23

- ↑ Faulkner, 1993 p. 104

- ↑ Pearlman and Werlock, 1991 p. 30

- ↑ Frye, 1995 p. 20: minor ellipsis for brevity, meaning unaltered.

- ↑ Frye, 1995 p. 21

- ↑ Pearlman and Werlock, 1991 p. 38: On Olsen's perennial theme of loss, of "[loss] of opportunity in 'Ironing'..."

- ↑ Frye, 1995 p. 23 And p. 36: The story "as part of a larger understanding of the need for social change."