Career

Duncan joined Western Mining Corporation (WMC Resources) in 1971 and remained with the company for 27 years. He commenced as operations manager of the company's exploration division, and rose to General Manager of the Olympic Dam mine. [4]

Dr Ian Duncan is a businessman active in the Australian resources sector. He is a past president of operations at the Olympic Dam mine in South Australia under Western Mining Corporation. [1] He was Chairman of the London-based Uranium Institute (now the World Nuclear Association) in 1995-1996. From the 1990s to the present, Duncan has advocated for nuclear industrial development in Australia, specifically the development of facilities to store and dispose of nuclear waste and the legalization and development of nuclear power plants for the generation of electricity. He is a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Technology, Science and Engineering (ATSE), [2] the Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy (AusIMM), and Engineers Australia. [3]

Duncan joined Western Mining Corporation (WMC Resources) in 1971 and remained with the company for 27 years. He commenced as operations manager of the company's exploration division, and rose to General Manager of the Olympic Dam mine. [4]

During the 2000s and 2010s, Duncan advocated for the development of nuclear power in Australia.

In 2005, Duncan described the status of breeder reactors as seeing "little advancement". He told the ABC that "There is abundant uranium to meet all future requirements for light water reactors that are planned around the world." [2] That year he also became a non-executive director of Perth-based company, Energy Ventures Ltd. [4] As of 2017, the company owns various uranium and energy exploration and development projects in Australia and internationally. The most advanced of these is the Aurora Uranium project in Oregon, USA. [5]

In 2006, Duncan described opponents of nuclear power as often using the subject of nuclear waste as a "tool". He argued that "due to global progress and example, the disposal of nuclear waste need not be a showstopper for nuclear power in Australia." [6]

In 2009, Duncan told The Age that he thought it was "time to seriously think about nuclear power as part of the baseload electricity generation. It's time that we moved along from the caveman attitude of just picking up and burning things. We should move to a higher order of source of energy." [7] He also referred to nuclear power as clean electricity with virtually no greenhouse gas emissions. He estimated that Australia's first nuclear power station could cost $6–8 billion and take ten years to design, build and commission. [8]

In April 2010, Duncan spoke at an event in Western Australia hosted by CEDA entitled "Assessing the Prospects of Nuclear Power in Australia". Michael Angwin of the Australian Uranium Association and Daniela Stehlik of the National Academies Forum also spoke at the event. [9]

In September 2010, Duncan told an Australian Institute of Energy Syposium held by the Perth Branch that he predicted that Australia's first nuclear reactors would be light-water reactors with a 600–1200 MWe capacity each, built in pairs, with sea water cooled condensers. They would be fueled with enriched uranium and spent nuclear fuel would ultimately be disposed of into ancient and stable underground rock storage facilities. [10]

Following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, Duncan remained optimistic about the prospect of nuclear power in Australia.

In 2013, he wrote that "if the economics for electricity generation is impacted by a carbon tax or a compulsory carbon capture and sequestration, then nuclear generation will be economically competitive." [11]

At a conference entitled "Nuclear Power for Australia?" held by ATSE in July of that year, he argued that if Australia were to aspire to produce electricity with nuclear power plants, a new Commonwealth agency 'inspectorate' with regulatory control over the choice of technology, siting, construction and operation should be established by 2016. [11] He proposed the working title Nuclear Installations Regulator for Australia (NIRA) and presented a detailed timeline of potential milestones to achieve between 2013 and criticality for the first reactor in 2030. His presentation flagged "Restart nuclear debate" as a first step, during the period 2014-2017. [12]

In 2015, a Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission commenced in South Australia tasked with investigating the opportunities and risks associated with South Australia's future role in the nuclear fuel cycle. Duncan's submission to the Royal Commission identified areas of the state's coastline he believed were potentially suitable for the siting of nuclear power plants. [13]

Duncan was a Member of the SYNROC Steering Committee (whose work was based on research and development undertaken by ANSTO and the ANU). [14]

In 2002, after his retirement, Duncan completed a doctorate at Oxford University considering the "interface between society and the disposal of radioactive waste". His publication was entitled "Radioactive Waste: Risk, Reward, Space and Time Dynamics" and he followed it with opinion pieces and media commentary on the subject during the early 2000s. [3] In 2003 he anticipated that "by far the biggest advancement will come from a better understanding of the public psyche by industry and not by a better understanding of the industry by the public." [15]

In 2003, he made the claim that "the Premier that supports the siting of a national repository will probably be remembered as the statesman who cleaned up Australia!" [3]

In the mid-2000s Duncan was actively consulting in the area, [6] [16] and was consulted during the Uranium Mining, Processing and Nuclear Energy Review (UMPNER) in 2006. [14]

In 2006, Duncan maintained the view that Australia had an obligation to appropriately manage its own, domestically produced nuclear waste. In an article published in Focus, the magazine of ATSE, he wrote:

"There is no justification for the importation of other countries’ radioactive waste, nor for participation in any so called ‘international attempts’ at nuclear waste disposal. Our moral obligation is to properly dispose of our own waste and that is achievable." [6]

In 2015 Duncan was appointed to the Independent Advisory Panel of the National Radioactive Waste Management Project for the Australian Government.

In September 2016, Duncan gave a presentation on the work of the Royal Commission and the National Radioactive Waste Management Project to members of the Minerals, Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Division of the Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining. During his talk he mentioned that 40 years had transpired since the Flower's Report was published in the UK, which prompted environmental consideration of the fate of nuclear wastes and their future management. [17]

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced by nuclear fission of uranium and plutonium in nuclear power plants. Nuclear decay processes are used in niche applications such as radioisotope thermoelectric generators in some space probes such as Voyager 2. Generating electricity from fusion power remains the focus of international research.

Radioactive waste is a type of hazardous waste that contains radioactive material. Radioactive waste is a result of many activities, including nuclear medicine, nuclear research, nuclear power generation, nuclear decommissioning, rare-earth mining, and nuclear weapons reprocessing. The storage and disposal of radioactive waste is regulated by government agencies in order to protect human health and the environment.

A nuclear power plant (NPP) is a thermal power station in which the heat source is a nuclear reactor. As is typical of thermal power stations, heat is used to generate steam that drives a steam turbine connected to a generator that produces electricity. As of 2022, the International Atomic Energy Agency reported there were 422 nuclear power reactors in operation in 32 countries around the world, and 57 nuclear power reactors under construction.

A non-renewable resource is a natural resource that cannot be readily replaced by natural means at a pace quick enough to keep up with consumption. An example is carbon-based fossil fuels. The original organic matter, with the aid of heat and pressure, becomes a fuel such as oil or gas. Earth minerals and metal ores, fossil fuels and groundwater in certain aquifers are all considered non-renewable resources, though individual elements are always conserved.

The Lucens reactor was a 6 MW experimental nuclear power reactor built next to Lucens, Vaud, Switzerland. After its connection to the electrical grid on 29 January 1968, the reactor only operated for a few months before it suffered an accident on 21 January 1969. The cause was a corrosion-induced loss of heat dispersal leading to the destruction of a pressure tube which caused an adjacent pressure tube to fail, and partial meltdown of the core, resulting in radioactive contamination of the cavern.

Haydon Manning is an Australian political scientist and Adjunct Professor with the College of Business, Government and Law at The Flinders University of South Australia.

In the United States, nuclear power is provided by 92 commercial reactors with a net capacity of 94.7 gigawatts (GW), with 61 pressurized water reactors and 31 boiling water reactors. In 2019, they produced a total of 809.41 terawatt-hours of electricity, which accounted for 20% of the nation's total electric energy generation. In 2018, nuclear comprised nearly 50 percent of US emission-free energy generation.

Uranium mining is the process of extraction of uranium ore from the ground. Over 50 thousand tons of uranium were produced in 2019. Kazakhstan, Canada, and Australia were the top three uranium producers, respectively, and together account for 68% of world production. Other countries producing more than 1,000 tons per year included Namibia, Niger, Russia, Uzbekistan, the United States, and China. Nearly all of the world's mined uranium is used to power nuclear power plants. Historically uranium was also used in applications such as uranium glass or ferrouranium but those applications have declined due to the radioactivity of uranium and are nowadays mostly supplied with a plentiful cheap supply of depleted uranium which is also used in uranium ammunition. In addition to being cheaper, depleted uranium is also less radioactive due to a lower content of short-lived 234

U and 235

U than natural uranium.

Hugh Matheson MorganAC, MAusIMM, FTSE,, is an Australian businessman and former CEO of Western Mining Corporation. He was President of the Business Council of Australia from 2003 to 2005. The Howard government appointed him to the board of the Reserve Bank of Australia in 1996, where he remained until 2007. He also was the Founding Chairman of Asia Society Australia.

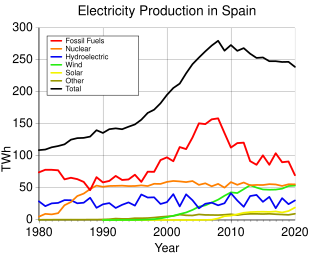

Spain has five active nuclear power plants with seven reactors producing 21% of the country's electricity as of 2013.

Nuclear power has various environmental impacts, including the construction and operation of the plant, the nuclear fuel cycle, and the effects of nuclear accidents. Nuclear power plants do not burn fossil fuels and so do not directly emit carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide emitted during mining, enrichment, fabrication and transport of fuel is small when compared with the carbon dioxide emitted by fossil fuels of similar energy yield, however, these plants still produce other environmentally damaging wastes. Nuclear energy and renewable energy have reduced environmental costs by decreasing CO2 emissions resulting from energy consumption.

Nuclear weapons testing, uranium mining and export, and nuclear power have often been the subject of public debate in Australia, and the anti-nuclear movement in Australia has a long history. Its origins date back to the 1972–1973 debate over French nuclear testing in the Pacific and the 1976–1977 debate about uranium mining in Australia.

The prospect of nuclear power in Australia has been a topic of public debate since the 1950s. Australia has one nuclear plant in Lucas Heights, Sydney, but is not used to produce nuclear power, but instead is used to produce medical radioisotopes. It also produces material or carries out analyses for the mining industry, for forensic purposes and for research. Australia hosts 33% of the world's uranium deposits and is the world's third largest producer of uranium after Kazakhstan and Canada.

The nuclear power debate is a long-running controversy about the risks and benefits of using nuclear reactors to generate electricity for civilian purposes. The debate about nuclear power peaked during the 1970s and 1980s, as more and more reactors were built and came online, and "reached an intensity unprecedented in the history of technology controversies" in some countries.

High-level radioactive waste management concerns how radioactive materials created during production of nuclear power and nuclear weapons are dealt with. Radioactive waste contains a mixture of short-lived and long-lived nuclides, as well as non-radioactive nuclides. There was reportedly some 47,000 tonnes of high-level nuclear waste stored in the United States in 2002.

Nuclear Power and the Environment, sometimes simply called the Flowers Report, was released in September 1976 and is the sixth report of the UK Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution, chaired by Sir Brian Flowers. The report was dedicated to "the Queen's most excellent Majesty." "He was appointed "to advise on matters, both national and international, concerning the pollution of the environment; on the adequacy of research in this field; and the future possibilities of danger to the environment." One of the recommendations of the report was that:

"There should be no commitment to a large programme of nuclear fission power until it has been demonstrated beyond reasonable doubt that a method exists to ensure the safe containment of longlived, highly radioactive waste for the indefinite future."

Belgium has two nuclear power plants operating with a net capacity of 5,761 MWe. Electricity consumption in Belgium has increased slowly since 1990 and in 2016 nuclear power provided 51.3%, 41 TWh per year, of the country's electricity.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to nuclear power:

Benjamin "Ben" Heard is a South Australian environmental consultant and an advocate for nuclear power in Australia, through his directorship of environmental NGO, Bright New World.

The Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission is a Royal Commission into South Australia's future role in the nuclear fuel cycle. It commenced on 19 March 2015 and delivered its final report to the Government of South Australia on 6 May 2016. The Commissioner was former Governor of South Australia, Kevin Scarce, a retired Royal Australian Navy Rear-Admiral and chancellor of the University of Adelaide. The Commission concluded that nuclear power was unlikely to be economically feasible in Australia for the foreseeable future. However, it identified an economic opportunity in the establishment of a deep geological storage facility and the receipt of spent nuclear fuel from prospective international clients.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)