Related Research Articles

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nicknamed "Supermac", he was known for his pragmatism, wit, and unflappability.

One-nation conservatism, also known as one-nationism or Tory democracy, is a paternalistic form of British political conservatism. It advocates the preservation of established institutions and traditional principles within a political democracy, in combination with social and economic programmes designed to benefit the ordinary person. According to this political philosophy, society should be allowed to develop in an organic way, rather than being engineered. It argues that members of society have obligations towards each other and particularly emphasises paternalism, meaning that those who are privileged and wealthy should pass on their benefits. It argues that this elite should work to reconcile the interests of all social classes, including labour and management, rather than identifying the good of society solely with the interests of the business class.

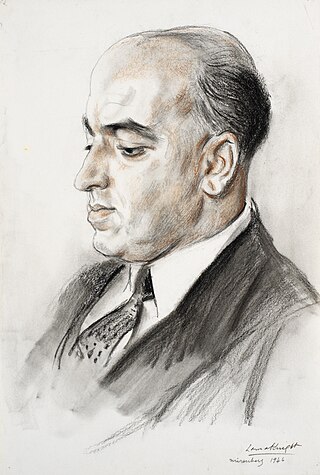

Richard Austen Butler, Baron Butler of Saffron Walden,, also known as R. A. Butler and familiarly known from his initials as Rab, was a prominent British Conservative Party politician which included a stint as Deputy Prime Minister. His obituary in The Times called him "the creator of the modern educational system, the key-figure in the revival of post-war Conservatism, arguably the most successful chancellor since the war and unquestionably a Home Secretary of reforming zeal". He was one of his party's leaders in promoting the post-war consensus through which the major parties largely agreed on the main points of domestic policy until the 1970s; it is sometimes known as "Butskellism" from a fusion of his name with that of his Labour counterpart, Hugh Gaitskell.

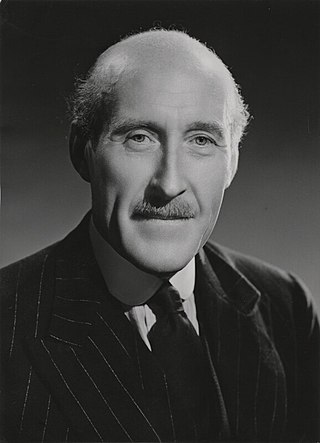

David Patrick Maxwell Fyfe, 1st Earl of Kilmuir,, known as Sir David Maxwell Fyfe from 1942 to 1954 and as Viscount Kilmuir from 1954 to 1962, was a British Conservative politician, lawyer and judge who combined an industrious and precocious legal career with political ambitions that took him to the offices of Solicitor General, Attorney General, Home Secretary and Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain.

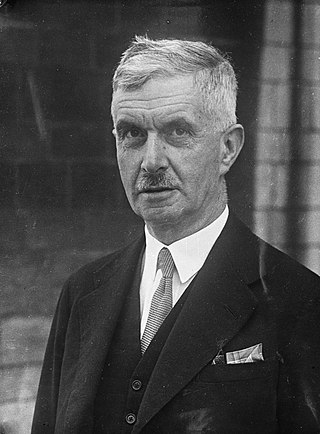

James Chuter Chuter-Ede, Baron Chuter-Ede,, was a British teacher, trade unionist and Labour Party politician. He was a Member of Parliament (MP) for 32 years, and served as the sole Home Secretary under Prime Minister Clement Attlee from 1945 to 1951, becoming the longest-serving Home Secretary of the 20th century.

The Education Act 1944 made major changes in the provision and governance of secondary schools in England and Wales. It is also known as the Butler Act after the President of the Board of Education, R. A. Butler. Historians consider it a "triumph for progressive reform," and it became a core element of the post-war consensus supported by all major parties. The Act was repealed in steps with the last parts repealed in 1996.

Oliver Frederick George Stanley was a prominent British Conservative politician who held many ministerial posts before his relatively early death.

Oliver Lyttelton, 1st Viscount Chandos, was a British businessman from the Lyttelton family who was brought into government during the Second World War, holding a number of ministerial posts.

Harry Frederick Comfort Crookshank, 1st Viscount Crookshank,, was a British Conservative politician. He was Minister of Health between 1951 and 1952 and Leader of the House of Commons between 1951 and 1955.

James Arthur Salter, 1st Baron Salter, was a British civil servant, politician, and academic who was involved in many efforts of international economic cooperation, often in conjunction with France's Jean Monnet.

Conservatives at Work (CaW), formerly Conservative Trade Unionists (CTU), is an organisation within the British Conservative Party made up of Conservative-supporting trade unionists. It played an important role in expanding the party's membership and influence, particularly in Britain's industrial regions. By building support within trade unions, the party contributed to the reduction of the power and influence of the left. Targeting the working class became a priority for the party. This was motivated by the idea that revulsion towards Labour's egalitarian goals and redistributive policies would emerge from this group.

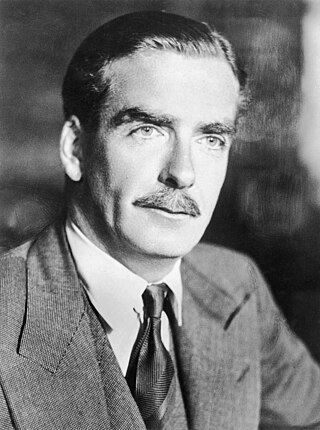

The Eden ministry was formed following the resignation of Winston Churchill in April 1955. Anthony Eden, then-Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary, took over as Leader of the Conservative Party, and thus became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Upon assuming office, Eden asked Queen Elizabeth II to dissolve parliament and called a general election for May 1955. After winning the general election with a majority of 60 seats in the House of Commons, Eden governed until his resignation on 10 January 1957.

Gaitskellism was the ideology of a faction in the British Labour Party in the 1950s and early 1960s which opposed many of the economic policies of the trade unions, especially nationalisation and control of the economy.

Paternalistic conservatism is a strand of conservatism which reflects the belief that societies exist and develop organically and that members within them have obligations towards each other. There is particular emphasis on the paternalistic obligation, referencing the feudal concept of noblesse oblige, of those who are privileged and wealthy to the poorer parts of society. Consistent with principles such as duty, hierarchy, and organicism, it can be seen as an outgrowth of traditionalist conservatism. Paternalistic conservatives do not support the individual or the state in principle but are instead prepared to support either or recommend a balance between the two depending on what is most practical.

Conservatism in the United Kingdom is related to its counterparts in other Western nations, but has a distinct tradition and has encompassed a wide range of theories over the decades of conservatism. The Conservative Party, which forms the mainstream right-wing party in Britain, has developed many different internal factions and ideologies.

Progressive conservatism is a political ideology that attempts to combine conservative and progressive policies. While still supportive of capitalist economy, it stresses the importance of government intervention in order to improve human and environmental conditions.

Stuart Ryan Ball, CBE, FRHistS, is a political historian who retired in 2016 as professor of Modern British History at the University of Leicester, having taught there for 37 years; he is now emeritus professor of Modern History there. He specialises in the history of the Conservative Party.

Richard Austen Butler, generally known as R. A. Butler and familiarly known from his initials as Rab, was a prominent British Conservative politician.

Richard Austen Butler, Baron Butler of Saffron Walden,, generally known as R. A. Butler and familiarly known from his initials as Rab, was a British Conservative politician.

When Britain emerged victorious from the Second World War, the Labour Party under Clement Attlee came to power and created a comprehensive welfare state, with the establishment of the National Health Service giving free healthcare to all British citizens, and other reforms to benefits. The Bank of England, railways, heavy industry, and coal mining were all nationalised. The most controversial issue was nationalisation of steel, which was profitable unlike the others. Economic recovery was slow, housing was in short supply, bread was rationed along with many necessities in short supply. It was an "age of austerity". American loans and Marshall Plan grants kept the economy afloat. India, Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon gained independence. Britain was a strong anti-Soviet factor in the Cold War and helped found NATO in 1949. Many historians describe this era as the "post-war consensus" emphasising how both the Labour and Conservative parties until the 1970s tolerated or encouraged nationalisation, strong trade unions, heavy regulation, high taxes, and a generous welfare state.

References

- ↑ R.A. Butler, The Art of the Possible: the Memoirs of Lord Butler, K.G., C.H. (London, 1971), p. 145.

- ↑ The Times, 'Conservative Policy for Industry', 3 October 1947.

- ↑ Conservative Central Office, The Industrial Charter (1947), pp. 11 and 13.

- ↑ CCO, The Industrial Charter, p. 1.

- ↑ CCO, The Industrial Charter, p. 4.

- ↑ Peter Dorey, British Conservatism and Trade Unionism, 1945-1964 (Farnham, 2009), p. 48.

- ↑ Butler 1971, p145, p148

- ↑ Jago, pp192-5"

- ↑ "The YMCA" had been a derogatory nickname for a group of younger progressive Conservatives in the 1920s.

- ↑ Butler 1971, pp133-4

- ↑ Anthony Howard, Rab: the life of R.A. Butler (London, 1987), p. 156.

- ↑ Ball 2004, pp.292-3

- ↑ Andrew Taylor, 'Speaking to Democracy: the Conservative Party and Mass Opinion from the 1920s to the 1950s', in Mass Conservatism: The Conservatives and the Public since the 1880s, eds. S. Ball and I. Holliday (London, 2002), pp. 78-99.

- ↑ Mass Observation, File Report 2516, 'The Industrial Charter' (1947), p. 8.

- ↑ The Economist, 'Mr Butskell's Dilemma', 13 February 1954.

- ↑ E.H.H. Green, 'The Conservative Party, the State and the Electorate, 1945-1964', in Party, State and Society: Electoral Behaviour in Britain since 1820 (Aldershot, 1997), 176-200 (pp. 179-80); John Ramsden, The Age of Churchill and Eden, 1940-1957 (London, 1995), p. 94; and R.A. Butler, The Art of the Possible, p. 126.