Aachen is the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia and the 27th-largest city of Germany, with around 261,000 inhabitants.

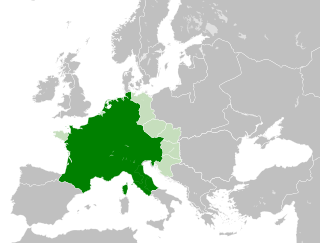

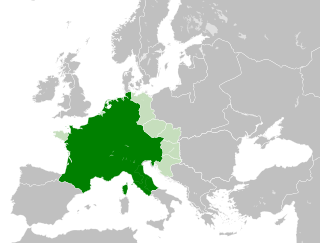

The Carolingian Empire (800–887) was a Frankish-dominated empire in Western and Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lombards in Italy from 774. In 800, the Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned emperor in Rome by Pope Leo III in an effort to transfer the status of Roman Empire from the Byzantine Empire to Western Europe. The Carolingian Empire is sometimes considered the first phase in the history of the Holy Roman Empire.

A palatine or palatinus is a high-level official attached to imperial or royal courts in Europe since Roman times. The term palatinus was first used in Ancient Rome for chamberlains of the Emperor due to their association with the Palatine Hill. The imperial palace guard, after the rise of Constantine I, were also called the Scholae Palatinae for the same reason. In the Early Middle Ages the title became attached to courts beyond the imperial one; one of the highest level of officials in the papal administration were called the judices palatini. Later the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties had counts palatine, as did the Holy Roman Empire. Related titles were used in Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, the German Empire, and the County of Burgundy, while England, Ireland, and parts of British North America referred to rulers of counties palatine as palatines.

Aachen Cathedral is a Catholic church in Aachen, Germany and the cathedral of the Diocese of Aachen.

Ingelheim, officially Ingelheim am Rhein, is a town in the Mainz-Bingen district in the Rhineland-Palatinate state of Germany. The town sprawls along the Rhine's left bank. It has been Mainz-Bingen's district seat since 1996.

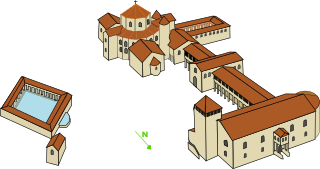

The Palatine Chapel in Aachen is an early medieval chapel and remaining component of Charlemagne's Palace of Aachen in what is now Germany. Although the palace itself no longer exists, the chapel was preserved and now forms the central part of Aachen Cathedral. It is Aachen's major landmark and a central monument of the Carolingian Renaissance. The chapel held the remains of Charlemagne. Later it was appropriated by the Ottonians and coronations were held there from 936 to 1531.

The term Kaiserpfalz or Königspfalz refers to a number of palaces and castles across the Holy Roman Empire that served as temporary seats of power for the Holy Roman Emperor in the Early and High Middle Ages.

Carolingian architecture is the style of north European Pre-Romanesque architecture belonging to the period of the Carolingian Renaissance of the late 8th and 9th centuries, when the Carolingian dynasty dominated west European politics. It was a conscious attempt to emulate Roman architecture and to that end it borrowed heavily from Early Christian and Byzantine architecture, though there are nonetheless innovations of its own, resulting in a unique character.

The Council of Frankfurt, traditionally also the Council of Frankfort, in 794 was called by Charlemagne, as a meeting of the important churchmen of the Frankish realm. Bishops and priests from Francia, Aquitaine, Italy, and Provence gathered in Franconofurd. The synod, held in June 794, allowed the discussion and resolution of many central religious and political questions.

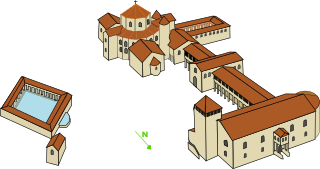

The Palace of Aachen was a group of buildings with residential, political, and religious purposes chosen by Charlemagne to be the center of power of the Carolingian Empire. The palace was located north of the current city of Aachen, today in the German Land of North Rhine-Westphalia. Most of the Carolingian palace was built in the 790s but the works went on until Charlemagne's death in 814. The plans, drawn by Odo of Metz, were part of the program of renovation of the kingdom decided by the ruler. Today much of the palace is ruined, but the Palatine Chapel has been preserved and is considered a masterpiece of Carolingian architecture and a characteristic example of architecture from the Carolingian Renaissance.

Imperial cathedral is the designation for a cathedral linked to the Imperial rule of the Holy Roman Empire.

A palas is a German term for the imposing or prestigious building of a medieval Pfalz or castle that contained the great hall. Such buildings appeared during the Romanesque period and, according to Thompson, are "peculiar to German castles".

An aula regia, also referred to as a palas hall, is a name given to the great hall in an imperial or royal palace. In the Middle Ages the term was also used as a synonym for the Pfalz itself.

The Chrysotriklinos, Latinized as Chrysotriclinus or Chrysotriclinium, was the main reception and ceremonial hall of the Great Palace of Constantinople from its construction, in the late 6th century, until the 10th century. Its appearance is known only through literary descriptions, chiefly the 10th-century De Ceremoniis, a collection of imperial ceremonies, but, as the chief symbol of imperial power, it inspired the construction of Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel in Aachen.

The Imperial Palace of Goslar is a historical building complex at the foot of the Rammelsberg hill in the south of the town of Goslar north of the Harz mountains, central Germany. It covers an area of about 340 by 180 metres. The palace grounds originally included the Kaiserhaus, the old collegiate church of St. Simon and St. Jude, the palace chapel of St. Ulrich and the Church of Our Lady (Liebfrauenkirche). The Kaiserhaus, which has been extensively restored in the late 19th century, was a favourite imperial residence, especially for the Salian emperors. As early as the 11th century, the buildings of the imperial palace had already so impressed the chronicler Lambert of Hersfeld that he described it as the "most famous residence in the empire". Since 1992, the palace site, together with the Goslar's Old Town and the Rammelsberg has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of its millennium-long association with mining and testimony to the exchange and advancement of mining technology throughout history.

The church known as Goslar Cathedral was a collegiate church dedicated to St. Simon and St. Jude in the town of Goslar, Germany. It was built between 1040 and 1050 as part of the Imperial Palace district. The church building was demolished in 1819–1822; today, only the porch of the north portal is preserved. It was a church of Benedictine canons. The term Dom, a German synecdoche used for collegiate churches and cathedrals alike, is often uniformly translated as 'cathedral' into English, even though this collegiate church was never the seat of a bishop.

The Basilica of St. Castor is the oldest church in Koblenz in the German state of Rhineland Palatinate. It is located near Deutsches Eck at the confluence of the Rhine and the Moselle. A fountain called Kastorbrunnen was built in front of the basilica during Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812. Pope John Paul II raised St. Castor to a basilica minor on 30 July 1991. This church is worth seeing for the historical events that have occurred in it, its extensive Romanesque construction and its largely traditional furnishings.

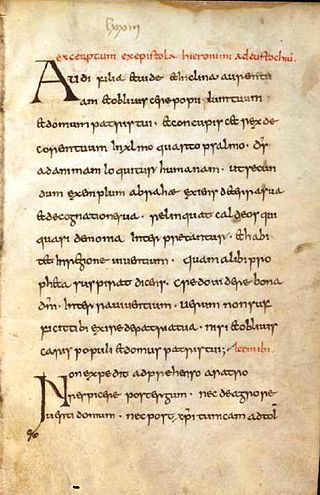

The Synods of Aachen between 816 and 819 were a landmark in regulations for the monastic life in the Frankish realm. The Benedictine Rule was declared the universally valid norm for communities of monks and nuns, while canonical orders were distinguished from monastic communities and unique regulations were laid down for them: the Institutio canonicorum Aquisgranensis. The synods of 817 and 818/819 completed the reforms. Among other things, the relationship of church properties to the king was clarified.

Salzburg Castle stands on the edge of a plateau above the town of Bad Neustadt an der Saale in Lower Franconia in southern Germany. The large Ganerbenburg is still partly occupied today and not all areas are accessible to the public.

The Imperial Palace at Gelnhausen is located on a former island in the Kinzig river in Gelnhausen, Hesse, Germany.