In Australian Aboriginal mythology, Mamaragan or Namarrkon is a lightning Ancestral Being who speaks with thunder as his voice. He rides a storm-cloud and throws lightning bolts to humans and trees. He lives in a puddle.

Arnhem Land is a historical region of the Northern Territory of Australia, with the term still in use. It is located in the north-eastern corner of the territory and is around 500 km (310 mi) from the territory capital, Darwin. In 1623, Dutch East India Company captain Willem Joosten van Colster sailed into the Gulf of Carpentaria and Cape Arnhem is named after his ship, the Arnhem, which itself was named after the city of Arnhem in the Netherlands.

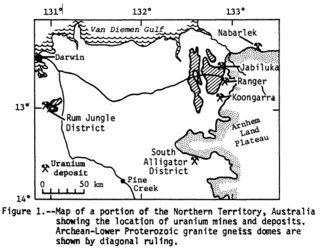

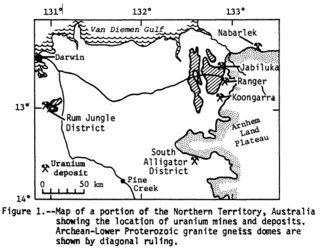

Alligator Rivers is the name of an area in an Arnhem Land region of the Northern Territory of Australia, containing three rivers, the East, West, and South Alligator Rivers. It is regarded as one of the richest biological regions in Australia, with part of the region in the Kakadu National Park. It is an Important Bird Area (IBA), lying to the east of the Adelaide and Mary River Floodplains IBA. It also contains mineral deposits, especially uranium, and the Ranger Uranium Mine is located there. The area is also rich in Australian Aboriginal art, with 1500 sites. The Kakadu National Park is one of the few World Heritage sites on the list because of both its natural and human heritage values. They were explored by Lieutenant Phillip Parker King in 1820, who named them in the mistaken belief that the crocodiles in the estuaries were alligators.

Bark painting is an Australian Aboriginal art form, involving painting on the interior of a strip of tree bark. This is a continuing form of artistic expression in Arnhem Land and other regions in the Top End of Australia, including parts of the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Traditionally, bark paintings were produced for instructional and ceremonial purposes and were transient objects. Today, they are keenly sought after by collectors and public arts institutions.

Gunbalanya is an Aboriginal Australian town in west Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia, about 300 kilometres (190 mi) east of Darwin. The main language spoken in the community is Kunwinjku. At the 2021 Australian census, Gunbalanya had a population of 1,177.

The Jim Jim Falls is a plunge waterfall on the Jim Jim Creek that descends over the Arnhem Land escarpment within the UNESCO World Heritage–listed Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory of Australia. The Jim Jim Falls area is registered on the Australian National Heritage List.

In February 1948, a team of Australian and American researchers and support staff came together in northern Australia to begin, what was then, one of the largest scientific expeditions ever to have taken place in Australia—the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land. Today it remains one of the most significant, most ambitious and least understood expeditions ever mounted.

Kunwinjku is a dialect of Bininj Kunwok, an Australian Aboriginal language. The Aboriginal people who speak Kunwinjku are the Bininj people, who live primarily in western Arnhem Land. As Kunwinjku is the most widely spoken dialect of Bininj Kunwok, 'Kunwinjku' is sometimes used to refer to Bininj Kunwok as a whole. Kunwinjku is spoken primarily in the west of the Bininj Kunwok speaking areas, including the town of Gunbalanya, as well as outstations such as Mamardawerre, Kumarrirnbang, Kudjekbinj and Manmoyi.

Bardayal "Lofty" Nadjamerrek was a Kunwinjku Aboriginal artist of the Mok clan. He belonged to the Duwa moiety and spoke the Kundedjnjenghmi language. He is currently referred to by his skin and clan as "Wamud Namok", following the Kunwinjku custom of avoiding use of the name of deceased persons.

The production of sculptural fibre objects has a long history within Aboriginal Australian culture. Historically, such objects had practical or ceremonial purposes, and some appeared in both contexts. The terms “art” and “craft” are difficult to apply in historical contexts, as they are not originally Aboriginal conceptual divisions. However, in a contemporary context, these objects are now generally regarded as contemporary art whenever they are presented as such. This categorisation is often applied to objects with historically practical or ceremonial applications, as well as a growing category of new fibre forms which have been innovated in the past decades and produced for a fine art market. The border between Aboriginal fibre sculpture and fibre craft is not clearly delineated, and some works may be regarded as either depending on the context of their display and use.

Tiwi Designs is an Aboriginal art centre located in Wurrumiyanga on Bathurst Island, north of Darwin, Australia. It holds a notable place in the history of the contemporary Aboriginal art movement as one of the longest running Aboriginal art centres, having started as a small screen-printing group in 1968-69. Only Ernabella Arts (1948) can establish a longer history.

Bobby Barrdjaray Nganjmirra was a Kunwinjku Aboriginal artist of the Djalama clan and Yirridjdja moiety. He was born around 1915 at Malworn in West Arnhem Land, growing up primarily in a traditional lifestyle despite short periods spent at school in Gunbalanya and on Goulburn Island. He is amongst the best known of the early modern Kunwinjku bark painters and was a contemporary of artists such as Bardayal 'Lofty' Nadjamerrek and Yirawala.

The Bininj are an Aboriginal Australian people of Western Arnhem land in the Northern Territory. The sub-groups of Bininj are sometimes referred to by the various language dialects spoken in the region, that is, the group of dialects known as Bininj Kunwok; so the people may be named the Kunwinjku, Kuninjku, Kundjeyhmi (Gundjeihmi), Manyallaluk Mayali, Kundedjnjenghmi and Kune groups.

Sally Kate May, usually cited as Sally K. May, is an Australian archaeologist and anthropologist. She is an Associate Professor of Archaeology and Museum Studies at the University of Adelaide, Australia. She is a specialist in Indigenous Australian rock art and Australian ethnographic museum collections.

Gabriel Maralngurra is an Aboriginal Australian artist from the Ngalangbali clan in West Arnhem Land. He is well-known and respected within his community for the wide range of responsibilities he takes on. His artwork is displayed in various collections including the Australia Museum, Museum Victoria, and the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia.

Wanurr Bob Namundja (c.1933–2005) was an Aboriginal Australian artist known for his bark paintings.

Joe Guymala is an Aboriginal Australian artist and musician of the Burdoh clan of the Kunwinjku people, known for his paintings on bark, paper and memorial poles known as lorrkkon.

Thompson Yulidjirri (1930-2009) was an Aboriginal Australian artist of the Kunwinjku people of western Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia. Yulidjirri was renowned for his wide knowledge of ancestral creation narratives and ceremony, his painting skills and mentorship of young artists at the Injalak Arts and Crafts centre.

Lucy Malirrimurruwuy Armstrong Wanapuyngu is an Aboriginal Australian master fibre artist. She is an elder of the Gapuwiyak community, and is heavily involved in the transmission of knowledge dealing with fibre works. She has worked with anthropologist Louise Hamby, since 1995, and many of her works have been spotlighted at different art festivals, collections, galleries, and museums.

Graham Badari is an Aboriginal Australian artist from the Wardjak clan in West Arnhem Land. Graham Badari belongs to the Duwa moeity and speaks the Kunwinjku dialect. At Injalak Arts, Badari is a popular figure, a tour guide, and a font of community news. Art historian Henry Skerritt describes him as possessing a "impish smile and cheeky sense of humour" and a "unique and eccentric personality"