Enactment

The Act was drafted principally by five people: Lewis Hunte, the then Attorney General of the British Virgin Islands; Neville Westwood, Michael Riegels and Richard Peters, who were partners at the law firm, Harneys; and Paul Butler, a partner from the U.S. law firm of Shearman & Sterling. [4] The Act was subsequently amended several times, but most significantly in 1990.

The Act was passed in a partial response to the cancellation by the U.S. government of a double taxation relief treaty between the British Virgin Islands and the United States. The British Virgin Islands was not alone in this regard; this was part of a policy of mass-repeal by the United States of double tax relief treaties with "microstates".

Despite the British Virgin Islands being an English common law jurisdiction, the Act drew heavily upon elements of Delaware corporate law. This reflected the market for British Virgin Islands companies prior to the repeal of the double-tax treaty. The essence of the Act was that a company incorporated under that legislation was prohibited from conducting business with people resident within the Territory (i.e. it was for International Business), and in exchange the company was exempt from all forms of British Virgin Islands taxation and stamp duty.

Parts of the Act were quite radical for the time. The Act abolished the concept of ultra vires for companies, [5] considerably restricted the requirement for corporate benefit, it permitted companies to change their corporate domicile from one jurisdiction to another, it allowed "true merger" of two different corporate entities, and introduced the concept of voting trusts to the jurisdiction.

The Act was passed into law by the Territory's legislature on 15 August 1984 where Chief Minister Cyril Romney hailed it as the most important legislation of the decade.

Growth

Initially, market response to the legislation was slow, but by 1988 a steady core of incorporation work was evident. However, in 1990 the U.S. invaded Panama and arrested General Manuel Noriega. At the time, Panama had been one of the market leaders in the provision of offshore companies. However, the invasion badly shook investor confidence in Panama, and incorporations in the British Virgin Islands under the Act soared from 1991 onwards.

From 1991 the Act was remarkably successful generating large numbers of incorporations. The Companies Registry in the Territory had to be expanded twice to cope with the volume of incorporations. The Act was then copied widely by other Caribbean offshore financial centres.

Despite its American focus, the key market for IBCs incorporated within the Territory developed in Hong Kong. Use of British Virgin Islands IBCs became so ubiquitous in Hong Kong, that in commercial jargon offshore companies generally were generically referred to there as "BVIs". [6]

In 2000, KPMG were commissioned by the British Government to produce a report on the offshore financial industry generally, and the report indicated that approximately 45% of the offshore companies in the world were formed in the British Virgin Islands, [7] making the British Virgin Islands one of the world's leading offshore financial centres. As a direct result the Territory has one of the highest incomes per capita in the Caribbean. [8]

Incorporations of IBCs| Year | Incorporations |

|---|

| 1984 | 1,000 |

| 1985 | 1,500 |

| 1986 | 1,700 |

| 1986 | 1,700 |

| 1987 | 2,000 |

| 1988 | 7,000 |

| 1989 | 9,500 |

| 1990 | 14,000 |

| 1991 | 15,000 |

| 1992 | 19,000 |

| 1993 | 27,000 |

| 1994 | 31,000 |

| 1995 | 30,000 |

| 1996 | 40,000 |

| 1997 | 60,000 |

|

Source: British Virgin Islands Financial Services Commission

Repeal

In 1999, a series of international initiatives were commenced against tax havens by supra-national bodies such as the OECD, including an initiative against what was termed "unfair tax competition". One of the concerns of the OECD was that jurisdictions such as the British Virgin Islands had a "ring fenced" tax regime, whereby companies could be incorporated under the International Business Companies Act which could not actually trade in the Territory, but would also be exempt from most British Virgin Islands taxes. After a series of discussions, the British Virgin Islands government agreed to repeal the ring-fencing provisions in its tax legislation. [9]

Because of the sheer volume of companies involved, the transition to a new legislative framework was accomplished over a two-year transition period. To protect the offshore business, the British Virgin Islands abolished both income tax and stamp duty on all transactions except those relating to land in the Territory. Then the government enacted the BVI Business Companies Act (No 16 of 2004). The slightly cumbersome name was designed to slightly reflect the name of the earlier statute and cash-in on the "IBC brand" which had grown under the former legislation. From 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2005 the two Acts ran in parallel, and it was possible to incorporate a company under either form of legislation. from 1 January 2006 until 31 December 2006, one could no longer incorporate a company under the International Business Companies Act, and all new incorporations had to be conducted under the BVI Business Companies Act. During 2006 detailed transitional provisions were enacted to allow companies formed under the old legislation to adapt to the new legislation without having to significantly amend their constitutional documents.

The International Business Companies Act was then finally repealed in full on 31 December 2006. [10]

A special arrangement between the BVI government and one of the key trust companies in the Territory meant that the last company incorporated under the Act was named "The Last IBC Limited". It was company number 690583.

The British Virgin Islands (BVI), officially the Virgin Islands, are a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean, to the east of Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands and north-west of Anguilla. The islands are geographically part of the Virgin Islands archipelago and are located in the Leeward Islands of the Lesser Antilles and part of the West Indies.

The economy of the British Virgin Islands is one of the most prosperous in the Caribbean. Although tiny in absolute terms, because of the very small population of the British Virgin Islands, in 2010 the Territory had the 19th highest GDP per capita in the world according to the CIA World factbook. In global terms the size of the Territory's GDP measured in terms of purchasing power is ranked as 215th out of a total of 229 countries. The economy of the Territory is based upon the "twin pillars" of financial services, which generates approximately 60% of government revenues, and tourism, which generates nearly all of the rest.

Corporate haven, corporate tax haven, or multinational tax haven is used to describe a jurisdiction that multinational corporations find attractive for establishing subsidiaries or incorporation of regional or main company headquarters, mostly due to favourable tax regimes, and/or favourable secrecy laws, and/or favourable regulatory regimes.

The term "offshore company" or “offshore corporation” is used in at least two distinct and different ways. An offshore company may be a reference to:

Offshore investment is the keeping of money in a jurisdiction other than one's country of residence. Offshore jurisdictions are used to pay less tax in many countries by large and small-scale investors. Poorly regulated offshore domiciles have served historically as havens for tax evasion, money laundering, or to conceal or protect illegally acquired money from law enforcement in the investor's country. However, the modern, well-regulated offshore centres allow legitimate investors to take advantage of higher rates of return or lower rates of tax on that return offered by operating via such domiciles. The advantage to offshore investment is that such operations are both legal and less costly than those offered in the investor's country—or "onshore".

An international business company or international business corporation (IBC) is an offshore company formed under the laws of some jurisdictions as a tax neutral company which is usually limited in terms of the activities it may conduct in, but not necessarily from, the jurisdiction in which it is incorporated. While not taxable in the country of incorporation, an IBC or its owners, if resident in a country having “controlled foreign corporation” rules for instance, can be taxable in other jurisdictions.

Harney Westwood & Riegels is a global offshore law firm that provides advice on British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Bermuda and Anguilla law to an international client base that includes law firms, financial institutions, investment funds, and private individuals. They have locations in major financial centers across Europe, Asia, the Americas and the Caribbean.

Michael Riegels was the inaugural chairman of the Financial Services Commission of the British Virgin Islands. He is a qualified barrister and was formerly the senior partner of Harneys from 1984 to 1997, and he also served the president of the BVI Bar Association from 1996 to 1998 and as president of the British Virgin Islands branch of the Red Cross.

Conyers is an international law firm. Their client base includes FTSE 100 and Fortune 500 companies, international finance houses and asset managers. The firm advises on law practiced in Bermuda, British Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands. Conyers Headquarters is situated in Hamilton, Bermuda and has international offices in Hong Kong, London and Singapore. Conyers also provides several corporate, trust, compliance, governance and accounting and management services.

The law of the British Virgin Islands is a combination of common law and statute, and is based heavily upon English law.

The BVI Business Companies Act is the principal statute of the British Virgin Islands relating to British Virgin Islands company law, regulating both offshore companies and local companies. It replaced the extremely popular and highly successful International Business Companies Act. It came into force on 1 January 2005.

Taxation in the British Virgin Islands is relatively simple by comparative standards; photocopies of all of the tax laws of the British Virgin Islands (BVI) would together amount to about 200 pages of paper.

A tax haven or tax den, is a jurisdiction with very low "effective" rates of taxation for foreign investors. In some traditional definitions, a tax haven also offers financial secrecy. However, while countries with high levels of secrecy but also high rates of taxation, most notably the United States and Germany in the Financial Secrecy Index ("FSI") rankings, can be featured in some tax haven lists, they are not universally considered as tax havens. In contrast, countries with lower levels of secrecy but also low "effective" rates of taxation, most notably Ireland in the FSI rankings, appear in most § Tax haven lists. The consensus on effective tax rates has led academics to note that the term "tax haven" and "offshore financial centre" are almost synonymous.

An offshore financial centre (OFC) is defined as a "country or jurisdiction that provides financial services to nonresidents on a scale that is incommensurate with the size and the financing of its domestic economy."

JPMorgan Chase Bank v. Traffic Stream (BVI) Infrastructure Ltd., 536 U.S. 88 (2002), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that a corporation organized under the laws of a British overseas territory is considered a "citizen or subject of a foreign state" for purposes of federal court jurisdiction.

The British Virgin Islands company law is the law that governs businesses registered in the British Virgin Islands. It is primarily codified through the BVI Business Companies Act, 2004, and to a lesser extent by the Insolvency Act, 2003 and by the Securities and Investment Business Act, 2010. The British Virgin Islands has approximately 30 registered companies per head of population, which is likely the highest ratio of any country in the world. Annual company registration fees provide a significant part of Government revenue in the British Virgin Islands, which accounts for the comparative lack of other taxation. This might explain why company law forms a much more prominent part of the law of the British Virgin Islands when compared to countries of similar size.

The Republic of Panama is one of the oldest and best-known tax havens in the Caribbean, as well as one of the most established in the region. Panama has had a reputation for tax avoidance since the early 20th century, and Panama has been cited repeatedly in recent years as a jurisdiction which does not cooperate with international tax transparency initiatives.

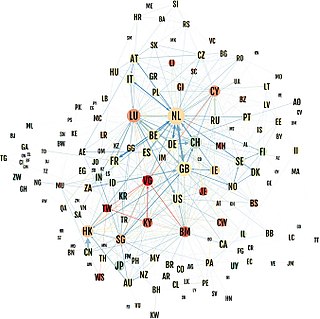

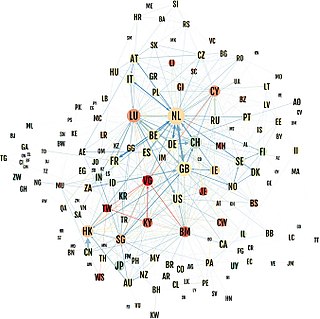

Conduit OFC and sink OFC is an empirical quantitative method of classifying corporate tax havens, offshore financial centres (OFCs) and tax havens.

James R. Hines Jr. is an American economist and a founder of academic research into corporate-focused tax havens, and the effect of U.S. corporate tax policy on the behaviors of U.S. multinationals. His papers were some of the first to analyse profit shifting, and to establish quantitative features of tax havens. Hines showed that being a tax haven could be a prosperous strategy for a jurisdiction, and controversially, that tax havens can promote economic growth. Hines showed that use of tax havens by U.S. multinationals had maximized long-term U.S. exchequer tax receipts, at the expense of other jurisdictions. Hines is the most cited author on the research of tax havens, and his work on tax havens was relied upon by the CEA when drafting the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

The Panama Papers are 11.5 million leaked documents that detail financial and attorney–client information for more than 214,488 offshore entities. The documents, some dating back to the 1970s, were created by, and taken from, Panamanian law firm and corporate service provider Mossack Fonseca, and were leaked in 2015 by an anonymous source.