Theoretical analyses

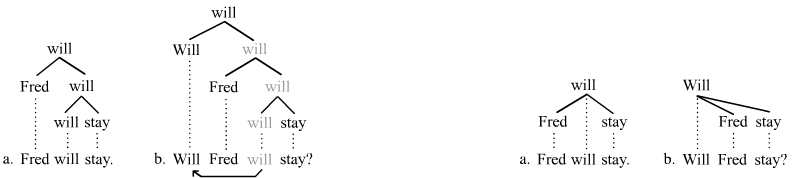

Syntactic inversion has played an important role in the history of linguistic theory because of the way it interacts with question formation and topic and focus constructions. The particular analysis of inversion can vary greatly depending on the theory of syntax that one pursues. One prominent type of analysis is in terms of movement in transformational phrase structure grammars. [11] Since those grammars tend to assume layered structures that acknowledge a finite verb phrase (VP) constituent, they need movement to overcome what would otherwise be a discontinuity. In dependency grammars, by contrast, sentence structure is less layered (in part because a finite VP constituent is absent), which means that simple cases of inversion do not involve a discontinuity; [12] the dependent simply appears on the other side of its head. The two competing analyses are illustrated with the following trees:

The two trees on the left illustrate the movement analysis of subject-auxiliary inversion in a constituency-based theory; a BPS-style (bare phrase structure) representational format is employed, where the words themselves are used as labels for the nodes in the tree. The finite verb will is seen moving out of its base position into a derived position at the front of the clause. The trees on the right show the contrasting dependency-based analysis. The flatter structure, which lacks a finite VP constituent, does not require an analysis in terms of movement but the dependent Fred simply appears on the other side of its head Will.

Pragmatic analyses of inversion generally emphasize the information status of the two noncanonically positioned phrases – that is, the degree to which the switched phrases constitute given or familiar information vs. new or informative information. Birner (1996), for example, draws on a corpus study of naturally occurring inversions to show that the initial preposed constituent must be at least as familiar within the discourse (in the sense of Prince 1992) as the final postposed constituent – which in turn suggests that inversion serves to help the speaker maintain a given-before-new ordering of information within the sentence. In later work, Birner (2018) argues that passivization and inversion are variants, or alloforms, of a single argument-reversing construction that, in turn, serves in a given instance as either a variant of a more general preposing construction or a more general postposing construction.

The overriding function of inverted sentences (including locative inversion) is presentational: the construction is typically used either to introduce a discourse-new referent or to introduce an event which in turn involves a referent which is discourse-new. The entity thus introduced will serve as the topic of the subsequent discourse. [13] Consider the following spoken Chinese example:

Zhènghǎo

Just

tóuli

ahead

guò-lai

pass-come

yí

one-CL

lǎotóur,

old-man

'Right then came over an old man.'

zhè

this

lǎotóur,

old.man

tā

3S

zhàn-zhe

stand-DUR

hái

still

bù

not

dònghuó

move

'this old man, he was standing without moving.' [14]

The constituent yí lǎotóur "an old man" is introduced for the first time into discourse in post-verbal position. Once it is introduced by the presentational inverted structure, it can be coded by the proximal demonstrative pronoun zhè 'this' and then by the personal pronoun tā – denoting an accessible referent: a referent that is already present in speakers' consciousness.