English

Modern English differs greatly in word order from other modern Germanic languages, but earlier English shared many similarities. For this reason, some scholars propose a description of Old English with V2 constraint as the norm. The history of English syntax is thus seen as a process of losing the constraint. [17]

Old English

In these examples, finite verb forms are in green, non-finite verb forms are in orange and subjects are blue.

Main clauses

Se

the

mæssepreost

masspriest

sceal

shall

manum

people

bodian

preach

þone

the

soþan

true

geleafan

faith

'The mass priest shall preach the true faith to the people.'

Hwi

Why

wolde

would

God

God

swa

so

lytles

small

þinges

thing

him

him

forwyrman

deny

'Why would God deny him such a small thing?'

on

in

twam

two

þingum

things

hæfde

has

God

God

þæs

the

mannes

man's

sawle

soul

geododod

endowed

'With two things God had endowed man's soul.'

þa

then

wæs

was

þæt

the

folc

people

þæs

of-the

micclan

great

welan

prosperity

ungemetlice

excessively

brucende

partaking

'Then the people were partaking excessively of the great prosperity.'

Ne

not

sceal

shall

he

he

naht

nothing

unaliefedes

unlawful

don

do

'He shall not do anything unlawful.'

Ðas

these

ðreo

three

ðing

things

forgifð

gives

God

God

he

his

gecorenum

chosen

'These three things God gives to his chosen

Position of object

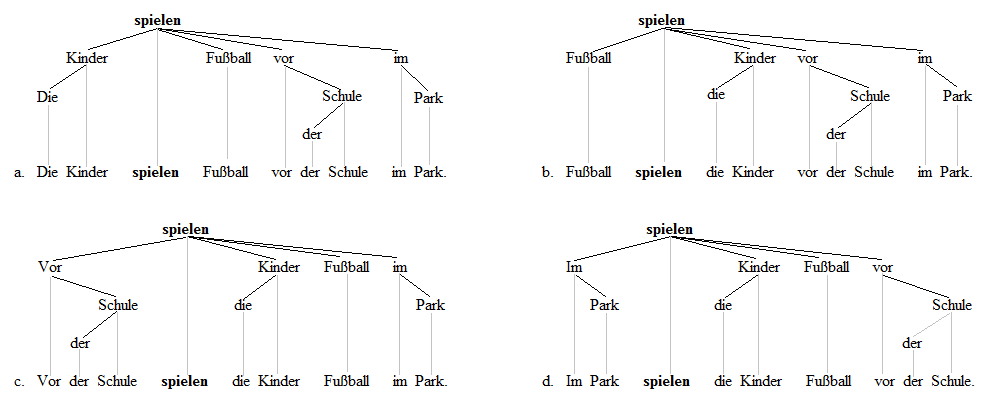

In examples b, c and d, the object of the clause precedes a non-finite verb form. Superficially, the structure is verb-subject-object- verb. To capture generalities, scholars of syntax and linguistic typology treat them as basically subject-object-verb (SOV) structure, modified by the V2 constraint. Thus Old English is classified, to some extent, as an SOV language. However, example a represents a number of Old English clauses with object following a non-finite verb form, with the superficial structure verb-subject-verb object. A more substantial number of clauses contain a single finite verb form followed by an object, superficially verb-subject-object. Again, a generalisation is captured by describing these as subject–verb–object (SVO) modified by V2. Thus Old English can be described as intermediate between SOV languages (like German and Dutch) and SVO languages (like Swedish and Icelandic).

Effect of subject pronouns

When the subject of a clause was a personal pronoun, V2 did not always operate.

forðon

therefore

we

we

sceolan

must

mid

with

ealle

all

mod

mind

&

and

mægene

power

to

to

Gode

God

gecyrran

turn

'Therefore, we must turn to God with all our mind and power

This section's factual accuracy is disputed .(May 2022) |

However, V2 verb-subject inversion occurred without exception after a question word or the negative ne, and with few exceptions after þa even with pronominal subjects.

for

for

hwam

what

noldest

not-wanted

þu

you

ðe sylfe

yourself

me

me

gecyðan

make-known

þæt...

that...

'wherefore would you not want to make known to me yourself that...'

Ne

not

sceal

shall

he

he

naht

nothing

unaliefedes

unlawful

don

do

'He shall not do anything unlawful.'

þa

then

foron

sailed

hie

they

mid

with

þrim

three

scipum

ships

ut

out

'Then they sailed out with three ships.'

Inversion of a subject pronoun also occurred regularly after a direct quotation. [18]

"Me

to me

is,"

is

cwæð

said

hēo

she

Þīn

your

cyme

coming

on

in

miclum

much

ðonce"

thankfulness

'"Your coming," she said, "is very gratifying to me".'

Embedded clauses

Embedded clauses with pronoun subjects were not subject to V2. Even with noun subjects, V2 inversion did not occur.

...þa ða

...when

his

his

leorningcnichtas

disciples

hine

him

axodon

asked

for

for

hwæs

whose

synnum

sins

se

the

man

man

wurde

became

swa

thus

blind

blind

acenned

'...when his disciples asked him for whose sins the man was thus born blind'

Yes–no questions

In a similar clause pattern, the finite verb form of a yes–no question occupied the first position

Truwast

trust

ðu

you

nu

now

þe

you

selfum

self

and

and

þinum

your

geferum

companions

bet

better

þonne

than

ðam

the

apostolum...?

apostles

'Do you now trust yourself and your companions better than the apostles...?'

Middle English

Continuity

Early Middle English generally preserved V2 structure in clauses with nominal subjects.

On

in

þis

this

gær

year

wolde

wanted

þe

the

king

king

Stephne

Stephen

tæcen

seize

Rodbert

Robert

'During this year King Stephen wanted to seize Robert.'

Nu

now

loke

look

euerich

every

man

man

toward

to

himseleun

himself

'Now it's for every man to look to himself.'

As in Old English, V2 inversion did not apply to clauses with pronoun subjects.

bi

by

þis

this

ȝe

you

mahen

may

seon

see

ant

and

witen...

know

alle

all

ðese

those

bebodes

commandments

ic

I

habbe

have

ihealde

kept

fram

from

childhade

childhood

Change

Late Middle English texts of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries show increasing incidence of clauses without the inversion associated with V2.

sothely

Truly

se

the

ryghtwyse

righteous

sekys

seeks

þe

the

loye

joy

and...

and...

And

And

by

by

þis

this

same

same

skyle

skill

hop

hope

and

and

sore

sorrow

shulle

shall

jugen

judge

us

us

Negative clauses were no longer formed with ne (or na) as the first element. Inversion in negative clauses was attributable to other causes.

why

why

ordeyned

ordained

God

God

not

not

such

such

ordre

order

'Why did God not ordain such an order?' (not follows noun phrase subject)

why

why

shulde

should

he

he

not...

not

(not precedes pronoun subject)

Ther

there

nys

not-is

nat

not

oon

one

kan

can

war

aware

by

by

other

other

be

be

'There is not a single person who learns from the mistakes of others'

He

He

was

was

despeyred;

in despair;

no thyng

nothing

dorste

dared

he

he

seye

say

Vestiges in Modern English

As in earlier periods, Modern English normally has subject-verb order in declarative clauses and inverted verb-subject order [19] in interrogative clauses. However these norms are observed irrespective of the number of clause elements preceding the verb.

Classes of verbs in Modern English: auxiliary and lexical

Inversion in Old English sentences with a combination of two verbs could be described in terms of their finite and non-finite forms. The word which participated in inversion was the finite verb; the verb which retained its position relative to the object was the non-finite verb. In most types of Modern English clause, there are two verb forms, but the verbs are considered to belong to different syntactic classes. The verbs which participated in inversion have evolved to form a class of auxiliary verbs which may mark tense, aspect and mood; the remaining majority of verbs with full semantic value are said to constitute the class of lexical verbs. The exceptional type of clause is that of declarative clause with a lexical verb in a present simple or past simple form.

Questions

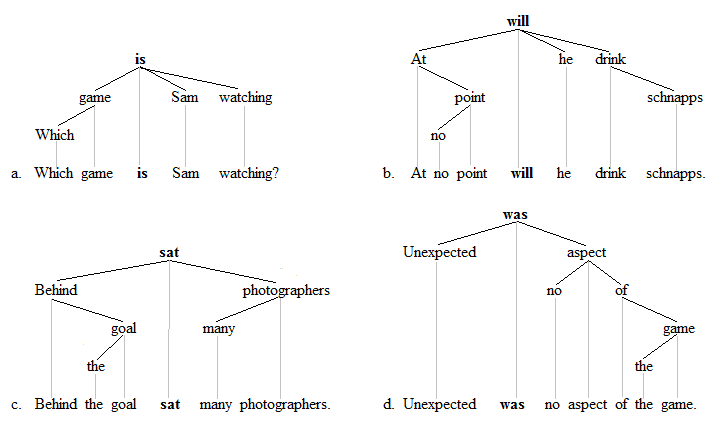

Like Yes/No questions, interrogative Wh- questions are regularly formed with inversion of subject and auxiliary. Present Simple and Past Simple questions are formed with the auxiliary do, a process known as do-support.

a. Which game is Sam watching? b. Where does she live? - (see subject-auxiliary inversion in questions)

With topic adverbs and adverbial phrases

In certain patterns similar to Old and Middle English, inversion is possible. However, this is a matter of stylistic choice, unlike the constraint on interrogative clauses.

negative or restrictive adverbial first

c. At no point will he drink Schnapps. d. No sooner had she arrived than she started to make demands. - (see negative inversion)

comparative adverb or adjective first

e. So keenly did the children miss their parents, they cried themselves to sleep. f. Such was their sadness, they could never enjoy going out.

After the preceding classes of adverbial, only auxiliary verbs, not lexical verbs, participate in inversion

locative or temporal adverb first

g. Here comes the bus. h. Now is the hour when we must say goodbye.

prepositional phrase first

i. Behind the goal sat many photographers. j. Down the road came the person we were waiting for. - (see locative inversion, directive inversion)

After the two latter types of adverbial, only one-word lexical verb forms (Present Simple or Past Simple), not auxiliary verbs, participate in inversion, and only with noun-phrase subjects, not pronominal subjects.

Direct quotations

When the object of a verb is a verbatim quotation, it may precede the verb, with a result similar to Old English V2. Such clauses are found in storytelling and in news reports.

k. "Wolf! Wolf!" cried the boy. l. "The unrest is spreading throughout the country," writes our Jakarta correspondent. - (see quotative inversion)

Declarative clauses without inversion

Corresponding to the above examples, the following clauses show the normal Modern English subject-verb order.

Declarative equivalents

a′. Sam iswatching the Cup games. b′. She lives in the country.

Equivalents without topic fronting

c′. He will at no point drink Schnapps. d′. She had no sooner arrived than she started to make demands. e′. The children missed their parents so keenly that they cried themselves to sleep. g′. The bus iscoming here. h′. The hour when we must say goodbye is now. i′. Many photographers sat behind the goal. j′. The person we were waiting for came down the road. k′. The boy cried "Wolf! Wolf!" l′. Our Jakarta correspondent writes, "The unrest is spreading throughout the country" .