Related Research Articles

In grammar, a ditransitiveverb is a transitive verb whose contextual use corresponds to a subject and two objects which refer to a theme and a recipient. According to certain linguistics considerations, these objects may be called direct and indirect, or primary and secondary. This is in contrast to monotransitive verbs, whose contextual use corresponds to only one object.

In linguistics, an object is any of several types of arguments. In subject-prominent, nominative-accusative languages such as English, a transitive verb typically distinguishes between its subject and any of its objects, which can include but are not limited to direct objects, indirect objects, and arguments of adpositions ; the latter are more accurately termed oblique arguments, thus including other arguments not covered by core grammatical roles, such as those governed by case morphology or relational nouns . In ergative-absolutive languages, for example most Australian Aboriginal languages, the term "subject" is ambiguous, and thus the term "agent" is often used instead to contrast with "object", such that basic word order is often spoken of in terms such as Agent-Object-Verb (AOV) instead of Subject-Object-Verb (SOV). Topic-prominent languages, such as Mandarin, focus their grammars less on the subject-object or agent-object dichotomies but rather on the pragmatic dichotomy of topic and comment.

In grammar, an oblique or objective case is a nominal case other than the nominative case and, sometimes, the vocative.

In linguistics, morphosyntactic alignment is the grammatical relationship between arguments—specifically, between the two arguments of transitive verbs like the dog chased the cat, and the single argument of intransitive verbs like the cat ran away. English has a subject, which merges the more active argument of transitive verbs with the argument of intransitive verbs, leaving the object distinct; other languages may have different strategies, or, rarely, make no distinction at all. Distinctions may be made morphologically, syntactically, or both.

In linguistic typology, nominative–accusative alignment is a type of morphosyntactic alignment in which subjects of intransitive verbs are treated like subjects of transitive verbs, and are distinguished from objects of transitive verbs in basic clause constructions. Nominative–accusative alignment can be coded by case-marking, verb agreement and/or word order. It has a wide global distribution and is the most common alignment system among the world's languages. Languages with nominative–accusative alignment are commonly called nominative–accusative languages.

In linguistics, a causative is a valency-increasing operation that indicates that a subject either causes someone or something else to do or be something or causes a change in state of a non-volitional event. Normally, it brings in a new argument, A, into a transitive clause, with the original subject S becoming the object O.

In linguistics, polypersonal agreement or polypersonalism is the agreement of a verb with more than one of its arguments. Polypersonalism is a morphological feature of a language, and languages that display it are called polypersonal languages.

The applicative voice is a grammatical voice that promotes an oblique argument of a verb to the core object argument. It is generally considered a valency-increasing morpheme. The Applicative is often found in agglutinative languages, such as the Bantu languages and Austronesian languages. Other examples include Nuxalk, Ubykh, and Ainu.

Nyangumarta, also written Njaŋumada, Njangamada, Njanjamarta and other variants, is a language spoken by the Nyangumarta people and other Aboriginal Australians in the region of Western Australia to the south and east of Lake Waukarlykarly, including Eighty Mile Beach, and part of the Great Sandy Desert inland to near Telfer. As of 2021 there were an estimated 240 speakers of Nyangumarta, down from a 1975 estimate of 1000.

In linguistics, dative shift refers to a pattern in which the subcategorization of a verb can take on two alternating forms, the oblique dative form or the double object construction form. In the oblique dative (OD) form, the verb takes a noun phrase (NP) and a dative prepositional phrase (PP), the second of which is not a core argument.

Tsez, also known as Dido, is a Northeast Caucasian language with about 15,000 speakers spoken by the Tsez, a Muslim people in the mountainous Tsunta District of southwestern Dagestan in Russia. The name is said to derive from the Tsez word for 'eagle', but this is most likely a folk etymology. The name Dido is derived from the Georgian word დიდი, meaning 'big'.

Gurindji Kriol is a mixed language which is spoken by Gurindji people in the Victoria River District of the Northern Territory (Australia). It is mostly spoken at Kalkaringi and Daguragu which are Aboriginal communities located on the traditional lands of the Gurindji. Related mixed varieties are spoken to the north by Ngarinyman and Bilinarra people at Yarralin and Pigeon Hole. These varieties are similar to Gurindji Kriol, but draw on Ngarinyman and Bilinarra which are closely related to Gurindji.

Wagiman, also spelt Wageman, Wakiman, Wogeman, and other variants, is a near-extinct Aboriginal Australian language spoken by a small number of Wagiman people in and around Pine Creek, in the Katherine Region of the Northern Territory.

Ughele is an Oceanic language spoken by about 1200 people on Rendova Island, located in the Western Province of the Solomon Islands.

Martin Haspelmath is a German linguist working in the field of linguistic typology. He is a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, where he worked from 1998 to 2015 and again since 2020. Between 2015 and 2020, he worked at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. He is also an honorary professor of linguistics at the University of Leipzig.

Adang is a Papuan language spoken on the island of Alor in Indonesia. The language is agglutinative. The Hamap dialect is sometimes treated as a separate language; on the other hand, Kabola, which is sociolinguistically distinct, is sometimes included. Adang, Hamap, and Kabola are considered a dialect chain. Adang is endangered as fewer speakers raise their children in Adang, instead opting for Indonesian.

Buru or Buruese is a Malayo-Polynesian language of the Central Maluku branch. In 1991 it was spoken by approximately 45,000 Buru people who live on the Indonesian island of Buru. It is also preserved in the Buru communities on Ambon and some other Maluku Islands, as well as in the Indonesian capital Jakarta and in the Netherlands.

Nen is a Yam language spoken in the Bimadbn village in the Western Province of Papua New Guinea, with 250 speakers as of a 2002 SIL survey. It is situated between the speech communities of Nambu and Idi.

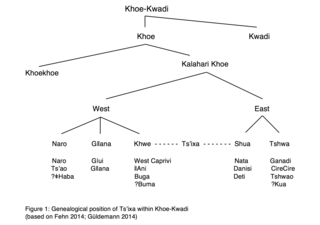

Tsʼixa is a critically endangered African language that belongs to the Kalahari Khoe branch of the Khoe-Kwadi language family. The Tsʼixa speech community consists of approximately 200 speakers who live in Botswana on the eastern edge of the Okavango Delta, in the small village of Mababe. They are a foraging society that consists of the ethnically diverse groups commonly subsumed under the names "San", "Bushmen" or "Basarwa". The most common term of self-reference within the community is Xuukhoe or 'people left behind', a rather broad ethnonym roughly equaling San, which is also used by Khwe-speakers in Botswana. Although the affiliation of Tsʼixa within the Khalari Khoe branch, as well as the genetic classification of the Khoisan languages in general, is still unclear, the Khoisan language scholar Tom Güldemann posits in a 2014 article the following genealogical relationships within Khoe-Kwadi, and argues for the status of Tsʼixa as a language in its own right. The language tree to the right presents a possible classification of Tsʼixa within Khoe-Kwadi:

In linguistic typology, object–subject (OS) word order, also called O-before-S or patient–agent word order, is a word order in which the object appears before the subject. OS is notable for its statistical rarity as a default or predominant word order among natural languages. Languages with predominant OS word order display properties that distinguish them from languages with subject–object (SO) word order.

References

- Blansitt, E.L. Jr. (1984). "Dechticaetiative and dative". In Objects, F. Plank (Ed.), 127–150. London: Academic Press.

- Comrie, Bernard (1975). "Antiergative." Papers from the 11th Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, R. E. Grossman, L. J. San, & T. J. Vance (eds.), 112-121.

- Dryer, Matthew S. (1986). "Primary objects, secondary objects, and antidative." Language 62:808-845.

- Haspelmath, Martin (2013). "Ditransitive Constructions: The Verb 'Give'." In: Dryer, Matthew S. & Haspelmath, Martin (eds.) The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. (Available online at , Accessed on 2014-03-02.)

- LaPolla, Randy (1992). "Anti-ergative Marking in Tibeto-Burman.” Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 15.1(1992):1-9.

- Malchukov, Andrej & Haspelmath, Martin & Comrie, Bernard (eds.) (2010). Studies in ditransitive constructions. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Trask, R. L. (1993). A Dictionary of Grammatical Terms in Linguistics Routledge, ISBN 0-415-08628-0