Related Research Articles

Haemophilia, or hemophilia, is a mostly inherited genetic disorder that impairs the body's ability to make blood clots, a process needed to stop bleeding. This results in people bleeding for a longer time after an injury, easy bruising, and an increased risk of bleeding inside joints or the brain. Those with a mild case of the disease may have symptoms only after an accident or during surgery. Bleeding into a joint can result in permanent damage while bleeding in the brain can result in long term headaches, seizures, or a decreased level of consciousness.

A blood-borne disease is a disease that can be spread through contamination by blood and other body fluids. Blood can contain pathogens of various types, chief among which are microorganisms, like bacteria and parasites, and non-living infectious agents such as viruses. Three blood-borne pathogens in particular, all viruses, are cited as of primary concern to health workers by the CDC-NIOSH: HIV, hepatitis B (HVB), & hepatitis C (HVC).

In the 1980s, between one and two thousand haemophilia patients in Japan contracted HIV via contaminated blood products. Controversy centered on the continued use of non-heat-treated blood products after the development of heat treatments that prevented the spread of infection. Some high-ranking officials in the Ministry of Health and Welfare, executives of the manufacturing company and a leading doctor in the field of haemophilia study were charged for involuntary manslaughter.

The tainted blood disaster, or the tainted blood scandal, was a Canadian public health crisis in the 1980s in which thousands of people were exposed to HIV and hepatitis C through contaminated blood products. It became apparent that inadequately-screened blood, often coming from high-risk populations, was entering the system through blood transfusions. It is now considered to be the largest single (preventable) public health disaster in the history of Canada.

The Irish Blood Transfusion Service (IBTS), or Seirbhís Fuilaistriúcháin na hÉireann in Irish, was established in Ireland as the Blood Transfusion Service Board (BTSB) by the Blood Transfusion Service Board (Establishment) Order, 1965. It took its current name in April 2000 by Statutory Instrument issued by the Minister for Health and Children to whom it is responsible. The Service provides blood and blood products for humans.

Factor 8: The Arkansas Prison Blood Scandal is a feature-length documentary by Arkansas filmmaker and investigative journalist Kelly Duda. Through interviews and presentation of documents and footage, Duda alleges that in the 1970s and 1980s, the Arkansas prison system profited from selling blood plasma from inmates infected with viral hepatitis and HIV. The documentary contends that thousands of victims who received transfusions of blood products derived from these plasma products, Factor VIII, died as a result.

Kelly Duda is an American filmmaker and activist from Arkansas best known for the 2005 documentary, Factor 8: The Arkansas Prison Blood Scandal.

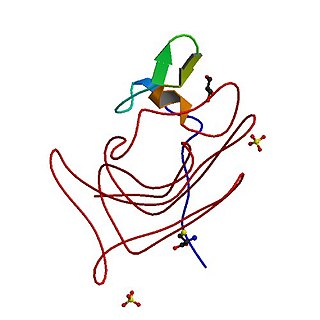

Contaminated hemophilia blood products were a serious public health problem in the late 1970s up to 1985.

The Lindsay Tribunal was set up in Ireland in 1999 to investigate the infection of haemophiliacs with HIV and Hepatitis C from contaminated blood products supplied by the Blood Transfusion Service Board.

In April 1991, the doctor and journalist Anne-Marie Casteret published an article in the French weekly magazine the L'Événement du jeudi showing that the Centre National de Transfusion Sanguine knowingly distributed blood products contaminated with HIV to haemophiliacs in 1984 and 1985, leading to an outbreak of HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C in numerous countries. It is estimated that 6,000 to 10,000 haemophiliacs were infected in the United States alone. In France, 4,700 people were infected, and over 300 died. Other impacted countries include Canada, Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Portugal, and the United Kingdom.

A transfusion transmitted infection (TTI) is a virus, parasite, or other potential pathogen that can be transmitted in donated blood through a transfusion to a recipient. The term is usually limited to known pathogens, but also sometimes includes agents such as simian foamy virus which are not known to cause disease.

In the 1970s and 1980s, a large number of people – most of whom had haemophilia – were infected with hepatitis C and HIV, the virus that leads to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), as a result of receiving contaminated clotting factor products. In England, these were supplied by NHS England. Many of the products were imported from the US.

David Maurice Surrey Dane, MRCS CRCP MB Bchir MRCP MRCPath FRCPath FRCP was a pre-eminent British pathologist and clinical virologist known for his pioneering work in infectious diseases including poliomyelitis and the early investigations into the efficacy of a number of vaccines. He is particularly remembered for his strategic foresight in the field of blood transfusion microbiology, particularly in relation to diseases that are spread through blood transfusion.

The Penrose Inquiry was the public inquiry into hepatitis C and HIV infections from NHS Scotland treatment with blood and blood products such as factor VIII, often used by people with haemophilia. The event is often called the Tainted Blood Scandal or Contaminated Blood Scandal.

Arthur Leslie Bloom FCRP, FRCPath (1930–1992) was a Welsh physician focused on the field of Haemophilia.

M.C. and Others v Italy is a case decided by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) on 3 September 2013 in which Article 1 of Protocol 1 (A1P1) was engaged due to the applicants not being afforded annual uprating which the court deemed damage to their property of a disproportionate character in the form of an exorbitant charge. The Strasbourg ruling sets an important precedent for higher monthly compensation payments to be paid to the 60,000 or so victims of contaminated blood transfusions in Italy. The effect of this ruling increased payments to the applicants by 40%.

A and Others v National Blood Authority and Another, also known as the Hepatitis C Litigation, was a landmark product liability case of 2001 primarily concerning blood transfusions but also blood products or transplanted organs, all of which were infected with hepatitis C, where liability was established under the Consumer Protection Act 1987 and the Product Liability Directive (85/374/EEC) even in the absence of the ability to test to ascertain which blood transfusions were defective. The claimants were 114 individuals, six of whom were considered lead plaintiffs and given close consideration by the judge, Mr Justice Burton. Several of the claimants were minors who had become infected with Hepatitis C in the course of their treatment for leukaemia. The defendants were the National Blood Authority (NBA) and in respect of Wales, the Velindre NHS Trust, Cardiff. The court found that the UK government should have implemented measures to screen donated blood for HCV by March 1990, rather than September 1991, and that surrogate testing should have been introduced within the United Kingdom no later than 1 March 1988.

The Advisory Committee on the Virological Safety of Blood, often abbreviated to ACVSB, was a committee formed in March 1989 in the United Kingdom to devise policy and advise ministers and the Department of Health on the safety of blood with respect to viral infections. The scope of the ACVSB concerned areas of significant policy for the whole of the United Kingdom and operated under the terms of reference: "To advise the Health Departments of the UK on measures to ensure the virological safety of blood, whilst maintaining adequate supplies of appropriate quality for both immediate use and for plasma processing." Of particular emphasis to the remit was the testing of blood donors using surrogate markers for Non-A Non-B hepatitis (NANBH) and later on, HCV-screening of blood donors.

The HIV Haemophilia Litigation [1990] 41 BMLR 171, [1990] 140 NLJR 1349 (CA), [1989] E N. 2111, also known as AMcG002, and HHL, was a legal claim by 962 plaintiffs, mainly haemophiliacs, who were infected with HIV as a result of having been treated with blood products in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The first central defendants were the then Department of Health, with other defendants being the Licensing Authority of the time, (MCA), the CSM, the CBLA, and the regional health authorities of England and Wales. In total, there were 220 defendants in the action.

In 1994, the Irish Blood Transfusion Service Board (BTSB) informed the Minister for Health that a blood product they had distributed in 1977 for the treatment of pregnant mothers had been contaminated with the hepatitis C virus. Following a report by an expert group, it was discovered that the BTSB had produced and distributed a second infected batch in 1991. The Government established a Tribunal of Inquiry to establish the facts of the case and also agreed to establish a tribunal for the compensation of victims but seemed to frustrate and delay the applications of these, in some cases terminally, ill women.

References

- ↑ McNally, Frank (13 January 1996). "Male victims of hepatitis C in the shadows". The Irish Times . Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ↑ "Hepatitis C tribunal of inquiry criticised by society". The Irish Times . 17 October 1996. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ↑ "Groups denied representation welcome High Court decision". The Irish Times . 26 November 1996. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ↑ McGarry, Patsy (14 December 1996). "Trauma of hepatitis discovery for haemophiliacs described". The Irish Times . Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ↑ Coulter, Carol (13 December 1996). "Haemophiliacs seek discovery of BTSB documents". The Irish Times . Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ↑ Mulqueen, Éibhir (21 January 1997). "System to treat anti D available in 1989". The Irish Times . Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ↑ "Terms of reference for HIV tribunal are likely to be drawn up next week". The Irish Times . 24 September 1997. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ↑ "Inquiry tribunal into infection of haemophiliacs opens today". The Irish Times . 27 September 1999. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "Judge grants full legal representation to three parties and limited to seven". The Irish Times . 28 September 1999. Retrieved 24 March 2022.