The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes and the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army. It took place on June 25–26, 1876, along the Little Bighorn River in the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana Territory. The battle, which resulted in the defeat of U.S. forces, was the most significant action of the Great Sioux War of 1876.

George Armstrong Custer was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Sitting Bull was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. Sitting Bull was killed by Indian agency police accompanied by U.S. officers and supported by U.S. troops on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation during an attempt to arrest him at a time when authorities feared that he would join the Ghost Dance movement.

Ashishishe, known as Curly and Bull Half White, was a Crow scout in the United States Army during the Sioux Wars, best known for having been one of the few survivors on the United States side at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. He did not fight in the battle, but may have watched from a distance, and was the first to report the defeat of the 7th Cavalry Regiment. Afterward a legend grew that he had been an active participant and managed to escape, leading to conflicting accounts of Curly's involvement in the historical record.

White Man Runs Him was a Crow scout serving with George Armstrong Custer's 1876 expedition against the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne that culminated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Goes Ahead was a Crow scout for George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry during the 1876 campaign against the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne. He was a survivor of the Battle of the Little Big Horn, and his accounts of the battle are valued by modern historians.

Son of the Morning Star: Custer and the Little Big Horn is a nonfiction account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876, by novelist Evan S. Connell, published in 1984 by North Point Press. The book features extensive portraits of the battle's participants, including General George Armstrong Custer, Sitting Bull, Major Marcus Reno, Captain Frederick Benteen, Crazy Horse, and others.

Gall, Lakota Phizí, was an important military leader of the Hunkpapa Lakota in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. He spent four years in exile in Canada with Sitting Bull's people, after the wars ended and surrendered in 1881 to live on the Standing Rock Reservation. He would eventually advocate for the assimilation of his people to reservation life and served as a tribal judge in his later years.

Bloody Knife was an American Indian who served as a scout and guide for the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment. He was the favorite scout of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and has been called "perhaps the most famous Native American scout to serve the U.S. Army."

White Bull later known as Joseph White Bull was the nephew of Sitting Bull, and a famous warrior in his own right. White Bull participated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876.

Dr. James Madison DeWolf was an acting assistant surgeon in the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment who was killed in the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

George Armstrong Custer (1839–1876) was a United States Army cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. He was defeated and killed by the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. More than 30 movies and countless television shows have featured him as a character. He was portrayed by future U.S. president, Ronald Reagan in Santa Fe Trail (1940), as well as by Errol Flynn in They Died With Their Boots On (1941).

Touch the Clouds was a chief of the Minneconjou Teton Lakota known for his bravery and skill in battle, physical strength and diplomacy in counsel. The youngest son of Lone Horn, he was brother to Spotted Elk, Frog, and Roman Nose. There is evidence suggesting that he was a cousin to Crazy Horse.

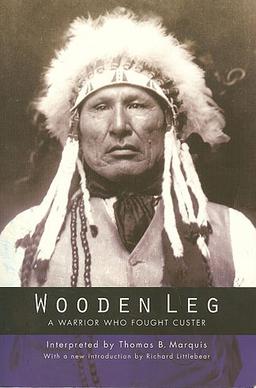

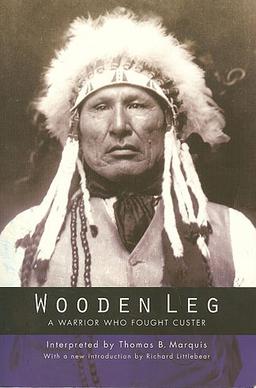

Wooden Leg: A Warrior Who Fought Custer is a 1931 book by Thomas Bailey Marquis about the life of a Northern Cheyenne Indian, Wooden Leg, who fought in several historic battles between United States forces and the Plains Indians, including the Battle of the Little Bighorn, where he faced the troops of George Armstrong Custer. The book is of great value to historians, not only for its eyewitness accounts of battles, but also for its detailed description of the way of life of 19th-century Plains Indians.

Frank Benjamin Grouard was a Scout and interpreter for General George Crook during the American Indian War of 1876. For the better part of a decade he lived with the Sioux tribe before returning to society. He was General Crook's lead scout at the Battle of the Rosebud participated in the Slim Buttes Fight, Battle of Red Fork, helped to assess the immediate aftermath of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, and participated in the Wounded Knee Massacre.

One Bull, sometimes given as Lone Bull, later known as Henry Oscar One Bull, was a Lakota Sioux man best known for being the nephew and adopted son of Sitting Bull. He fought at Battle of the Little Bighorn and, in his later years, provided interviews about his life as a warrior.

Low Dog (c. 1846–1894) was an Oglala Lakota chief who fought with Sitting Bull at the Little Bighorn.

Crow Scouts worked with the United States Army in several conflicts, the first in 1876 during the Great Sioux War. Because the Crow Nation was at that time at peace with the United States, the army was able to enlist Crow warriors to help them in their encroachment against the Native Americans with whom they were at war. In 1873, the Crow called for U.S. military actions against the Lakota people they reported were trespassing into the newly designated Crow reservation territories.

White Swan (c.1850—1904), or Mee-nah-tsee-us in the Crow language, was one of six Crow Scouts for George Armstrong Custer's 7th Cavalry Regiment during the 1876 campaign against the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne. At the Battle of the Little Bighorn in the Crow Indian Reservation, White Swan went with Major Reno's detachment, and fought alongside the soldiers at the south end of the village. Of the six Crow scouts at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, White Swan stands out because he aggressively sought combat with multiple Sioux and Cheyenne warriors, and he was the only Crow Scout to be wounded in action, suffering severe wounds to his hand/wrist and leg/foot. After being disabled by his wounds, he was taken to Reno's hill entrenchments by Half Yellow Face, the pipe-bearer (leader) of the Crow scouts, which no doubt saved his life.

Half Yellow Face was the leader of the six Crow Scouts for George Armstrong Custer's 7th Cavalry during the 1876 campaign against the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne. Half Yellow Face led the six Crow scouts as Custer advanced up the Rosebud valley and crossed the divide to the Little Bighorn valley, and then as Custer made the fateful decision to attack the large Sioux-Cheyenne camp which precipitated the Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876. At this time, the other Crow Scouts witnessed a conversation between Custer and Half Yellow Face. Half Yellow Face made a statement to Custer that was poetically prophetic, at least for Custer: "You and I are going home today by a road we do not know".