Related Research Articles

The year 1300 (MCCC) was a leap year starting on Friday in the Julian calendar, the 1300th year of the Common Era (CE) and Anno Domini (AD) designations, the 300th year of the 2nd millennium, the 100th and last year of the 13th century, and the 1st year of the 1300s. The year 1300 was not a leap year in the Proleptic Gregorian calendar.

Jacques de Molay, also spelled "Molai", was the 23rd and last grand master of the Knights Templar, leading the order sometime before 20 April 1292 until it was dissolved by order of Pope Clement V in 1312. Though little is known of his actual life and deeds except for his last years as Grand Master, he is one of the best known Templars.

Hethum II, OFM was king of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia from 1289 to 1293, 1295 to 1296 and 1299 to 1303, while Armenia was a subject state of the Mongol Empire. He abdicated twice to take vows with the Franciscans, while still remaining the power behind the throne as "Grand Baron of Armenia" and later as Regent for his nephew.

Mahmud Ghazan was the seventh ruler of the Mongol Empire's Ilkhanate division in modern-day Iran from 1295 to 1304. He was the son of Arghun, grandson of Abaqa Khan and great-grandson of Hulegu Khan, continuing a long line of rulers who were direct descendants of Genghis Khan. Considered the most prominent of the il khans, he is perhaps best known for converting to Islam and meeting Imam Ibn Taymiyya in 1295 when he took the throne, marking a turning point for the dominant religion of the Mongols in West Asia: Iran, Iraq, Anatolia, and the South Caucasus.

Mulay, Mûlay, Bulay was a general under the Mongol Ilkhanate ruler Ghazan at the end of the 13th century. Mulay was part of the 1299–1300 Mongol offensive in Syria and Palestine, and remained with a small force to occupy the land after the departure of Ghazan. He also participated in the last Mongol offensive in the Levant in 1303. His name has caused confusion for some historians, because of its similarity with that of the contemporary Grand Master of the Knights Templar, Jacques de Molay.

Starting in the 1240s, the Mongols made repeated invasions of Syria or attempts thereof. Most failed, but they did have some success in 1260 and 1300, capturing Aleppo and Damascus and destroying the Ayyubid dynasty. The Mongols were forced to retreat within months each time by other forces in the area, primarily the Egyptian Mamluks. The post-1260 conflict has been described as the Mamluk–Ilkhanid War.

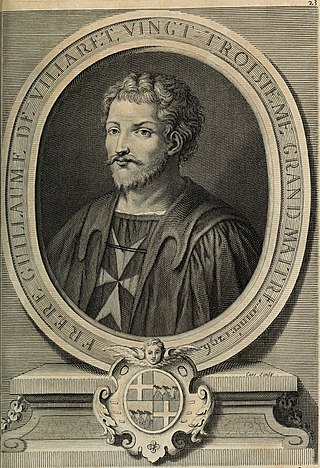

Guillaume de Villaret, was the twenty-fourth Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller, a position he held from 1296 until 1305, succeeding Odon de Pins. He was succeeded by his nephew, Foulques de Villaret, whose career he had done much to advance.

Hayton of Corycus, O.Praem was a medieval Armenian nobleman and historiographer. He was also a member of Norbertines and likely a Catholic priest.

Buscarello de Ghizolfi, also known as Buscarel of Gisolfe, was a European who settled in Persia in the 13th century while it was part of the Mongol Ilkhanate. He was a Mongol ambassador to Europe from 1289 to 1305, serving the Mongol rulers Arghun, Ghazan and then Oljeitu. The goal of the communications was to form a Franco-Mongol alliance between the Mongols and the Europeans against the Muslims, but despite many back-and-forth communications, the attempts were never successful.

Several attempts at a military alliance between the Frankish Crusaders and the Mongol Empire against the Islamic caliphates, their common enemy, were made by various leaders among them during the 13th century. Such an alliance might have seemed an obvious choice: the Mongols were already sympathetic to Christianity, given the presence of many influential Nestorian Christians in the Mongol court. The Franks—Western Europeans, and those in the Levantine Crusader states—were open to the idea of support from the East, in part owing to the long-running legend of the mythical Prester John, an Eastern king in an Eastern kingdom who many believed would one day come to the assistance of the Crusaders in the Holy Land. The Franks and Mongols also shared a common enemy in the Muslims. However, despite many messages, gifts, and emissaries over the course of several decades, the often-proposed alliance never came to fruition.

Jean II de Giblet was a Christian prince of the House of Giblet, an area of the Holy Land, in the 13th-14th century. His family used to be located in the fief of Cerep in Antioch, before the area was taken by the Mamluks. He was married to Marguerite du Plessis.

Mongol raids into Palestine took place towards the end of the Crusades, following the temporarily successful Mongol invasions of Syria, primarily in 1260 and 1300. Following each of these invasions, there existed a period of a few months during which the Mongols were able to launch raids southward into Palestine, reaching as far as Gaza.

Tommaso Ugi di Siena was a 14th-century Italian adventurer, native of the city of Siena in Italy. He resided at the court of the Mongol Ilkhanid ruler Oljeitu in the Persian capital of Tabriz, where he held the high position of Ildüchi, "Sword bearer", for Oljeitu. Other adventurers, such as Buscarello de Ghizolfi or Isol the Pisan, are known to have played similar roles at the Mongol court. Hundreds such Western adventurers entered into the service of Mongol rulers.

Kutlushah, Kutlusha or Qutlughshah, was a general under the Mongol Ilkhanate ruler Ghazan at the end the 13th century. He was particularly active in the Christian country of Georgia and especially during the Mongol invasion of Syria, until his ignominious defeat in 1303 led to his banishment. He was killed during the conquest of Gilan in 1307.

A Byzantine-Mongol Alliance occurred during the end of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th century between the Byzantine Empire and the Mongol Empire. Byzantium attempted to maintain friendly relations with both the Golden Horde and the Ilkhanate realms, and was caught in the middle of growing conflict between the two. The alliance involved numerous exchanges of presents, military collaboration and marital links, but dissolved in the middle of the 14th century.

Nerses Balients, also Nerses Balienc or Nerses Bagh'on, was a Christian Armenian monk of the early 14th century. He is mainly known for writing a history of the Kingdom of Cilician Armenia. Though his works are regarded by modern scholars as a valuable source from the time period, they are also regarded as frequently unreliable.

Guiscard Bustari was a Florentine Italian adventurer and ambassador, who was employed by the Mongol Il Khan ruler Ghazan.

The fall of Ruad in 1302 was one of the culminating events of the Crusades in the Eastern Mediterranean. In 1291, the Crusaders had lost their main power base at the coastal city of Acre, and the Muslim Mamluks had been systematically destroying the remaining Crusader ports and fortresses in the region, forcing the Crusaders to relocate the dwindling Kingdom of Jerusalem to the island of Cyprus. In 1299–1300, the Cypriots sought to retake the Syrian port city of Tortosa, by setting up a staging area on Ruad, two miles (3 km) off the coast of Tortosa. The plans were to coordinate an offensive between the forces of the Crusaders, and those of the Ilkhanate. However, though the Crusaders successfully established a bridgehead on the island, the Mongols did not arrive, and the Crusaders were forced to withdraw the bulk of their forces to Cyprus. The Knights Templar set up a permanent garrison on the island in 1300, but the Mamluks besieged and captured Ruad in 1302. With the loss of the island, the Crusaders lost their last foothold in the Holy Land and it marked the end of their presence in the Levant region.

Mongol Armenia or Ilkhanid Armenia refers to the period beginning in the early-to-mid 13th century during which both Zakarid Armenia and the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia became tributary and vassal to the Mongol Empire and the successor Ilkhanate. Armenia and Cilicia remained under Mongol influence until around 1335.

The fall of Outremer describes the history of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from the end of the last European Crusade to the Holy Land in 1272 until the final loss in 1302. The kingdom was the center of Outremer—the four Crusader states—formed after the First Crusade in 1099 and reached its peak in 1187. The loss of Jerusalem in that year began the century-long decline. The years 1272–1302 are fraught with many conflicts throughout the Levant as well as the Mediterranean and Western European regions, and many Crusades were proposed to free the Holy Land from Mamluk control. The major players fighting the Muslims included the kings of England and France, the kingdoms of Cyprus and Sicily, the three Military Orders and Mongol Ilkhanate. Traditionally, the end of Western European presence in the Holy Land is identified as their defeat at the Siege of Acre in 1291, but the Christian forces managed to hold on to the small island fortress of Ruad until 1302.

References

- Demurger, Alain (2007). Jacques de Molay. Editions Payot.

- Richard, Jean (1970). "Isol le Pisan: Un aventurier franc gouverneur d'une province mongole?" Central Asiatic Journal, 14: 186–94.

- Richard, Jean. Histoire des Croisades. Fayard.

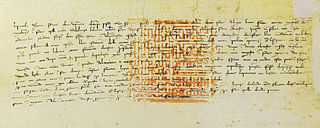

- Schein, Sylvia (1979). "Gesta Dei per Mongolos 1300. The Genesis of a Non-Event." English Historical Review , 94:373 (October), pp. 805–819.

- Sinor, Denis (1975). "The Mongols and Western Europe." A History of the Crusades III: The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, Harry W. Hazard, ed. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

- M. Balard, “Génois et Pisans en Orient (fin du XIIIe-début du XIVe siècle)”, in Atti Società ligure di storia patria, n.s. Vol. XXIV (XCVIII), fasc. II, Genova, Società ligure di storia patria, [1984], pp. 179–209.

- M. Chiaverini, "Il ‘Porto Pisano’ alla foce del Don tra il XIII e XIV secolo", Pisa, MARICH, 2000, pp. 51–52.