Related Research Articles

The Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment is an international human rights treaty under the review of the United Nations that aims to prevent torture and other acts of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment around the world.

Cruel and unusual punishment is a phrase in common law describing punishment that is considered unacceptable due to the suffering, pain, or humiliation it inflicts on the person subjected to the sanction. The precise definition varies by jurisdiction, but typically includes punishments that are arbitrary, unnecessary, or overly severe compared to the crime.

Torture in Bahrain refers to the violation of Bahrain's obligations as a state party to the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and other international treaties and disregard for the prohibition of torture enshrined in Bahraini law.

Juan E. Méndez is an Argentine lawyer, former United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and a human rights activist known for his work on behalf of political prisoners.

Manfred Nowak is an Austrian human rights expert, who served as the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture from 2004 to 2010. He is Secretary General of the Global Campus of Human Rights in Venice, Italy, Professor of International Human Rights, and Scientific Director of the Vienna Master of Arts in Applied Human Rights at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. He is also co-founder and former Director of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Human Rights and a former judge at the Human Rights Chamber for Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 2016, he was appointed Independent Expert leading the United Nations Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty.

The International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT) is an independent, international health professional organization that promotes and supports the rehabilitation of torture victims and works for the prevention of torture worldwide. Based in Denmark, the IRCT is the umbrella organization for over 160 independent torture rehabilitation organizations in 76 countries that treat and assist torture survivors and their families. They advocate for holistic rehabilitation for all victims of torture, which can include access to justice, reparations, and medical, psychological, and psycho-social counseling. The IRCT does this through strengthening the capacity of their membership, enabling an improved policy environment for torture victims, and generating and share knowledge on issues related to the rehabilitation of torture victims. Professionals at the IRCT rehabilitation centers and programs provide treatment for an estimated 100,000 survivors of torture every year. Victims receive multidisciplinary support including medical and psychological care and legal aid. The aim of the rehabilitation process is to empower torture survivors to resume as full a life as possible. In 1988, IRCT, along with founder Inge Genefke, was given the Right Livelihood Award "for helping those whose lives have been shattered by torture to regain their health and personality."

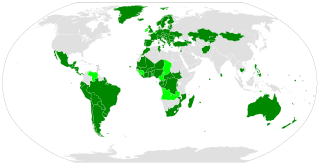

The Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture (IACPPT) is an international human rights instrument, created in 1985 within the Western Hemisphere Organization of American States and intended to prevent torture and other similar activities.

In law, sex characteristic refers to an attribute defined for the purposes of protecting individuals from discrimination due to their sexual features. The attribute of sex characteristics was first defined in national law in Malta in 2015. The legal term has since been adopted by United Nations, European, and Asia-Pacific institutions, and in a 2017 update to the Yogyakarta Principles on the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics.

The Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment is a treaty that supplements to the 1984 United Nations Convention Against Torture. It establishes an international inspection system for places of detention modeled on the system that has existed in Europe since 1987.

The Human Rights Foundation of Turkey is headquartered in Ankara. The organization is committed to treating torture survivors and documenting human rights violations in daily bulletins, monthly and annual special reports in Turkish and English languages.

Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights prohibits torture, and "inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment".

Article 3 – Prohibition of torture

No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

The widespread and systematic use of torture in Turkey goes back to the Ottoman Empire. After the foundation of the Republic of Turkey, torture of civilians by the Turkish Armed Forces and Turkish police was widespread during the Dersim rebellion. The Sansaryan Han police headquarters and Harbiye Military Prison in Istanbul became known for torture in the 1940s. Amnesty International (AI) first documented Turkish torture after the 1971 Turkish coup d'état and has continued to issue critical reports, particularly after the outbreak of the Kurdish-Turkish conflict in the 1980s. The Committee for the Prevention of Torture has issued critical reports on the extent of torture in Turkey since the 1990s. The Stockholm Center for Freedom published a report entitled Mass Torture and Ill-Treatment in Turkey in June 2017. The Human Rights Foundation of Turkey estimates there are around one million victims of torture in Turkey.

The UN Principles of Medical Ethics is a code of medical ethics relating to the "roles of health personnel in the protection of persons against torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.", adopted by the United Nations on 18 December 1982 at the 111th plenary meeting of the United Nations General Assembly.

Naji Ali Hassan Fateel is a Bahraini human rights activist and member of the Board of Directors of the Bahraini human rights NGO Bahrain Youth Society for Human Rights (BYSHR). Since 2007 he has been imprisoned, tortured and the target of death threats during the Bahraini uprising (2011–present). He has been the subject of urgent appeals by international human rights organisations and the United nations special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders.

Papua New Guinea (PNG) has a population of 6.8 million, nearly half of which is under 18 years of age. Public trust in the justice system has been eroded, and the country’s significant crime problem exacerbated, by brutal responses from police against those they suspect of having committed offences, and the routine violence, abuse and rape carried out by police against persons, including children, within their custody. Many incidents are cases of opportunistic abuses of power by police instead of their following official processes. While a raft of measures have been assembled in order to improve conditions and processes for youths within the justice system, their success has been hampered by a severe lack of implementation, insufficient resources, and failure to impose appropriate penalties on authorities for failure to adhere to their provisions.

The Minnesota Protocol on the Investigation of Potentially Unlawful Death (2016) is a set of international guidelines for the investigation of suspicious deaths, particularly those in which the responsibility of a State is suspected.

Cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment (CIDT) is treatment of persons which is contrary to human rights or dignity, but is not classified as torture. It is forbidden by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, the United Nations Convention against Torture and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Although the distinction between torture and CIDT is maintained from a legal point of view, medical and psychological studies have found that it does not exist from the psychological point of view, and people subjected to CIDT will experience the same consequences as survivors of torture. Based on this research, some practitioners have recommended abolishing the distinction.

The prohibition of torture is a peremptory norm in public international law—meaning that it is forbidden under all circumstances—as well as being forbidden by international treaties such as the United Nations Convention Against Torture.

The Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts for Bolivia is a committee of jurists and human rights experts created by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to carry out a parallel investigation of human rights violations during the 2019 Bolivian political crisis, covering the period from 1 September 2019 to 31 December 2019. The group was established following discussions between the IACHR and the interim Bolivian government led by Jeanine Áñez in December 2019, and an agreement between the two in January 2020. Its four members were appointed on 23 January 2020. The Group was supported by a five-member technical team and the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team. The Group began its work in Bolivia on 23 November 2020 and issued its final report on 23 July 2021.

On June 8, 2023, the governments of Canada and The Netherlands brought a case against Syria before the International Court of Justice accusing the Syrian Government of torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment of its own population beginning at least in 2011 and failing to fulfill its obligations regarding the prohibition against torture violating the United Nations Convention Against Torture.

References

- ↑ "Julian Assange asks UN special rapporteur to 'Please save my life'". Personal Liberty . 2019-09-16. Retrieved 2019-09-16.

It followed the 'Istanbul Protocol'. The protocol's full name is the 'Manual on Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.'

- ↑ "Istanbul Protocol: Manual on the Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (2022 edition)". UNHCR. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ↑ Vincent Iacopino; Onder Ozkalipci; Caroline Schlar (1999-09-25). "The Istanbul Protocol: international standards for the effective investigation and documentation of torture and ill treatment". The Lancet . Vol. 354, no. 9184. p. 1117. Archived from the original on 2012-10-04. Retrieved 2019-09-16.