Boris Feodorovich Godunov was the de facto regent of Russia from 1585 to 1598 and then tsar from 1598 to 1605 following the death of Feodor I, the last of the Rurik dynasty. After the end of his reign, Russia descended into the Time of Troubles.

Ivan IV Vasilyevich, commonly known as Ivan the Terrible, was Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533, and Tsar of all Russia, from 1547 until his death in 1584. He was the first Russian monarch to be crowned as tsar.

Oprichnik was the designation given to a member of the Oprichnina, a bodyguard corps established by Tsar Ivan the Terrible to govern a division of Russia from 1565 to 1572.

Simeon Bekbulatovich was a Russian statesman of Tatar origin who briefly served as the figurehead ruler of Russia from 1575 to 1576. He was a descendant of Genghis Khan.

The oprichnina was a state policy implemented by Tsar Ivan the Terrible in Russia between 1565 and 1572. The policy included mass repression of the boyars, including public executions and confiscation of their land and property. In this context it can also refer to:

The Tale of Tsar Saltan, of His Son the Renowned and Mighty Bogatyr Prince Gvidon Saltanovich and of the Beautiful Swan-Princess is an 1831 fairy tale in verse by Alexander Pushkin.

False Dmitry I reigned as the Tsar of all Russia from 10 June 1605 until his death on 17 May 1606 under the name of Dmitriy Ivanovich. According to historian Chester S. L. Dunning, Dmitry was "the only Tsar ever raised to the throne by means of a military campaign and popular uprisings".

Anastasia Romanovna Zakharyina-Yurieva was the tsaritsa of all Russia as the first wife of Ivan IV, the tsar of all Russia. She was also the mother of Feodor I, the last lineal Rurikid tsar of Russia, and the great-aunt of Michael of Russia, the first tsar of the Romanov dynasty.

The Chelyadnin family (Челяднины) were an old and influential Russian boyar family who served the Grand Princes of Moscow in high and influential positions. They were descended from Ratsha, court servant (tiun) to Prince Vsevolod II of Kiev.

Vladimir Andreyevich was the last appanage Russian prince. His complicated relationship with his cousin, Ivan the Terrible, was dramatized in Sergei Eisenstein's 1944 film Ivan the Terrible.

Ivan the Terrible is a two-part Soviet epic historical drama film written and directed by Sergei Eisenstein. A biopic of Ivan IV of Russia, it was Eisenstein's final film, commissioned by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin.

Ivan Tsarevich is one of the main heroes of Russian folklore, usually a protagonist, often engaged in a struggle with Koschei. Along with Ivan the Fool, Ivan Tsarevich is a placeholder name, meaning "Prince Ivan", rather than a definitive character. Tsarevich is a title given to the sons of tsars.

The massacre of Novgorod was an attack launched by Ivan the Terrible's oprichniki on the city of Novgorod, Russia, in 1570. Although initially an act of vengeance against the perceived treason of the local Orthodox church, the massacre quickly became possibly the most vicious in the brutal legacy of the oprichnina, with casualties estimated between two thousand to fifteen thousand and innumerable acts of extreme, violent cruelty. In the aftermath of the attack, Novgorod lost its status as one of Russia's leading cities, crippled by decimation of its citizenry combined with Ivan's assault on the surrounding farmlands.

The Tsardom of Russia, also known as the Tsardom of Muscovy, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of tsar by Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter the Great in 1721.

Maureen Perrie is a British historian, Professor Emeritus of Russian History at the University of Birmingham, and a lecturer in Russian History at the centre for Russian and East European Studies at the University of Birmingham.

Ivan Ivanovich was the second son of Russian tsar Ivan the Terrible by his first wife Anastasia Romanovna. He was the tsarevich until he suddenly died; historians generally believe that his father killed him in a fit of rage.

Maria Temryukovna was the tsaritsa of all Russia from 1561 until her death as the second wife of Ivan the Terrible, the tsar of all Russia.

Wish upon a Pike, also known as The Magic Fish, is a 1938 fantasy film directed by Alexander Rowe, which was his debut and filmed at Soyuzdetfilm. It is adapted from a play by Yelizaveta Tarakhovskaya, itself based on At the Pike's Behest and other tales from Slavic folklore. At the time it was made, it was seen as controversial in the Soviet Union to direct films based on fairy tales due to government censorship.

Yefrosinya Andreyevna Staritskaya was a Russian noblewoman. She was married to Andrey of Staritsa, the younger brother of Vasili III and an uncle of Ivan IV.

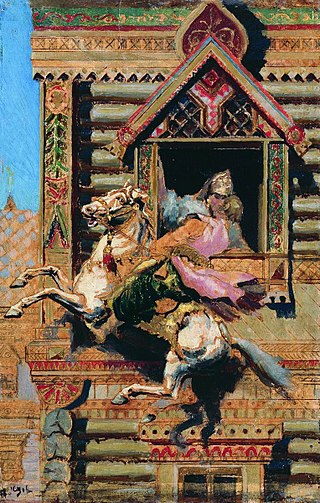

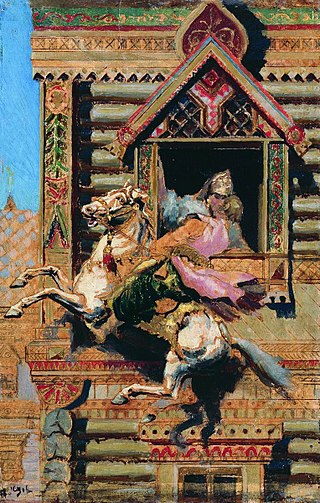

Sivko-Burko is a Russian fairy tale (skazka) collected by folklorist Alexandr Afanasyev in his three-volume compilation Russian Fairy Tales. The tale is a local form in Slavdom of tale type ATU 530, "The Princess on the Glass Mountain", wherein the hero has to jump higher and reach a tower or terem, instead of climbing up a steep and slippery mountain made entirely of glass.