Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishment of communism. Lenin's ideological contributions to the Marxist ideology relate to his theories on the party, imperialism, the state, and revolution. The function of the Leninist vanguard party is to provide the working classes with the political consciousness and revolutionary leadership necessary to depose capitalism.

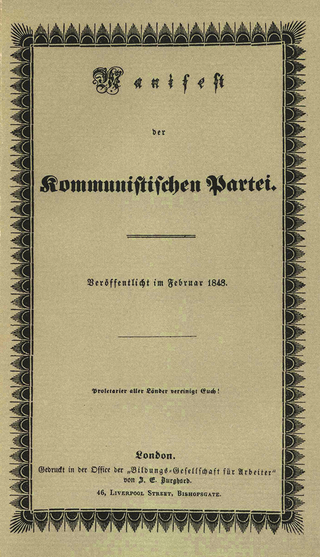

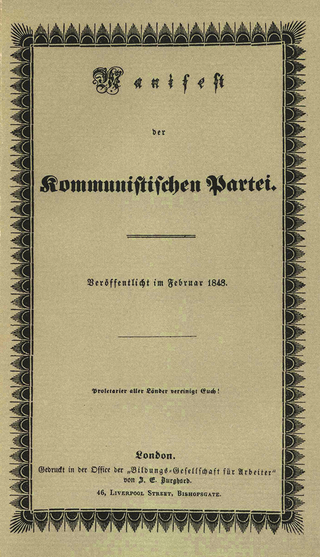

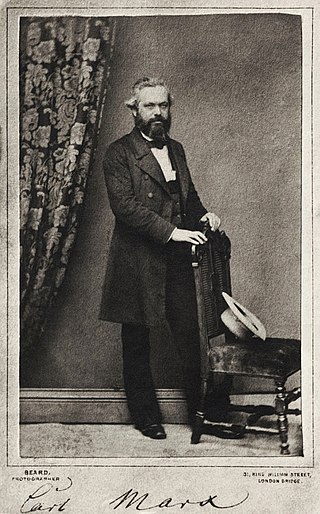

The Communist Manifesto, originally the Manifesto of the Communist Party, is a political pamphlet written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London in 1848. The text is the first and most systematic attempt by Marx and Engels to codify for wide consumption the historical materialist idea that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles", in which social classes are defined by the relationship of people to the means of production. Published amid the Revolutions of 1848 in Europe, the Manifesto remains one of the world's most influential political documents.

Invariance is a French magazine edited by Jacques Camatte, published since 1968.

Amadeo Bordiga was an Italian Marxist theorist. A revolutionary socialist, Bordiga was the founder of the Communist Party of Italy (PCdI), member of the Communist International (Comintern), and later a leading figure of the Internationalist Communist Party (PCInt). He was originally associated with the PCdI but was expelled in 1930 after being accused of Trotskyism. Bordiga is viewed as one of the most notable representatives of left communism in Europe.

In Marxism, ultra-leftism encompasses a broad spectrum of revolutionary communist currents that are generally Marxist and frequently anti-Leninist in perspective. Ultra-leftism distinguishes itself from other left-wing currents through its rejection of electoralism, trade unionism, and national liberation. The term is sometimes used as a synonym of left communism. "Ultra-left" is also commonly used as a pejorative by Marxist–Leninists and Trotskyists to refer to extreme or uncompromising Marxist sects.

The Communist Workers' Party of Germany was an anti-parliamentarian and left communist party that was active in Germany during the Weimar Republic. It was founded in 1920 in Heidelberg as a split from the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Originally the party remained a sympathising member of Communist International. In 1922, the KAPD split into two factions, both of whom kept the name, but are referred to as the KAPD Essen Faction and the KAPD Berlin Faction.

The International Communist Party (ICP) is a left communist international political party.

Communization theory refers to a tendency on the ultra-left that understands communism as a process that, in a social revolution, immediately begins to replace all capitalist social relations with communist ones. Thus it rejects the role of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which it sees as reproducing capitalism. There exist two broad trends within communization theory: a ‘Marxist’ one and an ‘Anarchist’ one.

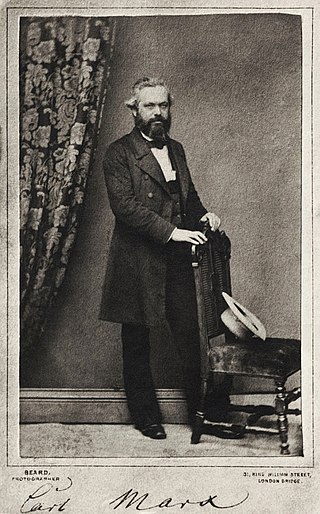

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that originates in the works of 19th century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism analyzes and critiques the development of class society and especially of capitalism as well as the role of class struggles in systemic, economic, social and political change. It frames capitalism through a paradigm of exploitation and analyzes class relations and social conflict using a materialist interpretation of historical development – materialist in the sense that the politics and ideas of an epoch are determined by the way in which material production is carried on.

In Marxism, a theoretician is an individual who observes and writes about the condition or dynamics of society, history, or economics, making use of the main principles of Marxian socialism in the analysis.

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices espoused by Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions which they regard as more authentically Marxist than the views of Marxism–Leninism espoused by the Communist International after its Bolshevization by Joseph Stalin and during its second congress.

Classical Marxism is the body of economic, philosophical, and sociological theories expounded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their works, as contrasted with orthodox Marxism, Marxism–Leninism, and autonomist Marxism which emerged after their deaths. The core concepts of classical Marxism include alienation, base and superstructure, class consciousness, class struggle, exploitation, historical materialism, ideology, revolution; and the forces, means, modes, and relations of production. Marx's political praxis, including his attempt to organize a professional revolutionary body in the First International, often served as an area of debate for subsequent theorists.

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolution is a necessary precondition for transitioning from a capitalist to a socialist mode of production. Revolution is not necessarily defined as a violent insurrection; it is defined as a seizure of political power by mass movements of the working class so that the state is directly controlled or abolished by the working class as opposed to the capitalist class and its interests.

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat, or working class, holds control over state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the transitional phase from a capitalist to a communist economy, whereby the post-revolutionary state seizes the means of production, mandates the implementation of direct elections on behalf of and within the confines of the ruling proletarian state party, and institutes elected delegates into representative workers' councils that nationalise ownership of the means of production from private to collective ownership. During this phase, the organizational structure of the party is to be largely determined by the need for it to govern firmly and wield state power to prevent counterrevolution, and to facilitate the transition to a lasting communist society.

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Western Marxism, which drew from various sources, and the official philosophy in the Soviet Union, which enforced a rigid reading of what Marx called dialectical materialism, in particular during the 1930s. Marxist philosophy is not a strictly defined sub-field of philosophy, because the diverse influence of Marxist theory has extended into fields as varied as aesthetics, ethics, ontology, epistemology, social philosophy, political philosophy, the philosophy of science, and the philosophy of history. The key characteristics of Marxism in philosophy are its materialism and its commitment to political practice as the end goal of all thought. The theory is also about the struggles of the proletariat and their reprimand of the bourgeoisie.

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country, sometimes referred to as a workers' state or workers' republic, is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. The term communist state is often used synonymously in the West, specifically when referring to one-party socialist states governed by Marxist–Leninist communist parties, despite these countries being officially socialist states in the process of building socialism and progressing toward a communist society. These countries never describe themselves as communist nor as having implemented a communist society. Additionally, a number of countries that are multi-party capitalist states make references to socialism in their constitutions, in most cases alluding to the building of a socialist society, naming socialism, claiming to be a socialist state, or including the term people's republic or socialist republic in their country's full name, although this does not necessarily reflect the structure and development paths of these countries' political and economic systems. Currently, these countries include Algeria, Bangladesh, Guyana, India, Nepal, Nicaragua, Sri Lanka and Tanzania.

Proletarian internationalism, sometimes referred to as international socialism, is the perception of all proletarian revolutions as being part of a single global class struggle rather than separate localized events. It is based on the theory that capitalism is a world-system and therefore the working classes of all nations must act in concert if they are to replace it with communism.

Permanent revolution is the strategy of a revolutionary class pursuing its own interests independently and without compromise or alliance with opposing sections of society. As a term within Marxist theory, it was first coined by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as early as 1850, but since then different theorists - most notably Leon Trotsky (1879–1940) - have used the phrase to refer to different concepts.

Roger Dangeville was a left communist activist most noted for his translation of Karl Marx's Grundrisse and his work with Jacques Camatte.