Related Research Articles

An anapsid is an amniote whose skull lacks one or more skull openings near the temples. Traditionally, the Anapsida are considered the most primitive subclass of amniotes, the ancestral stock from which Synapsida and Diapsida evolved, making anapsids paraphyletic. It is, however, doubtful that all anapsids lack temporal fenestra as a primitive trait, and that all the groups traditionally seen as anapsids truly lacked fenestra.

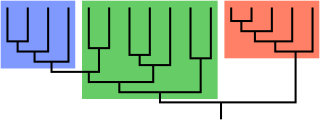

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolved from amphibian ancestors during the Carboniferous period and further diverged into two groups, namely the sauropsids and synapsids. They are distinguished from the other living tetrapod clade — the non-amniote lissamphibians — by the development of three extraembryonic membranes, thicker and keratinized skin, and costal respiration.

Sauria is the clade containing the most recent common ancestor of Archosauria and Lepidosauria, and all its descendants. Since most molecular phylogenies recover turtles as more closely related to archosaurs than to lepidosaurs as part of Archelosauria, Sauria can be considered the crown group of diapsids, or reptiles in general. Depending on the systematics, Sauria includes all modern reptiles or most of them as well as various extinct groups.

Diapsids are a clade of sauropsids, distinguished from more primitive eureptiles by the presence of two holes, known as temporal fenestrae, in each side of their skulls. The group first appeared about three hundred million years ago during the late Carboniferous period. All diapsids other than the most primitive ones in the clade Araeoscelidia are sometimes placed into the clade Neodiapsida. The diapsids are extremely diverse, and include birds and all modern reptile groups, including turtles, which were historically thought to lie outside the group. Although some diapsids have lost either one hole (lizards), or both holes, or have a heavily restructured skull, they are still classified as diapsids based on their ancestry. At least 17,084 species of diapsid animals are extant: 9,159 birds, and 7,925 snakes, lizards, tuatara, turtles, and crocodiles.

Sauropsida is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern reptiles and birds. The most popular definition states that Sauropsida is the sibling taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early synapsids have historically been referred to as "mammal-like reptiles", all synapsids are more closely related to mammals than to any modern reptile. Sauropsids, on the other hand, include all amniotes more closely related to modern reptiles than to mammals. This includes Aves (birds), which are recognized as a subgroup of archosaurian reptiles despite originally being named as a separate class in Linnaean taxonomy.

The International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature, known as the PhyloCode for short, is a formal set of rules governing phylogenetic nomenclature. Its current version is specifically designed to regulate the naming of clades, leaving the governance of species names up to the rank-based nomenclature codes.

Mesosaurs were a group of small aquatic reptiles that lived during the early Permian period (Cisuralian), roughly 299 to 270 million years ago. Mesosaurs were the first known aquatic reptiles, having apparently returned to an aquatic lifestyle from more terrestrial ancestors. It is uncertain which and how many terrestrial traits these ancestors displayed; recent research cannot establish with confidence if the first amniotes were fully terrestrial, or only amphibious. Most authors consider mesosaurs to have been aquatic, although adult animals may have been amphibious, rather than completely aquatic, as indicated by their moderate skeletal adaptations to a semiaquatic lifestyle. Similarly, their affinities are uncertain; they may have been among the most basal sauropsids or among the most basal parareptiles.

Archosauriformes is a clade of diapsid reptiles encompassing archosaurs and some of their close relatives. It was defined by Jacques Gauthier (1994) as the clade stemming from the last common ancestor of Proterosuchidae and Archosauria. Phil Senter (2005) defined it as the most exclusive clade containing Proterosuchus and Archosauria. Archosauriforms are a branch of archosauromorphs which originated in the Late Permian and persist to the present day as the two surviving archosaur groups: crocodilians and birds.

Archosauromorpha is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs rather than lepidosaurs. Archosauromorphs first appeared during the late Middle Permian or Late Permian, though they became much more common and diverse during the Triassic period.

The Batrachomorpha are a clade containing extant and extinct amphibians that are more closely related to modern amphibians than they are to mammals and reptiles. According to many analyses they include the extinct Temnospondyli; some show that they include the Lepospondyli instead. The name traditionally indicated a more limited group.

Reptiliomorpha is a clade containing the amniotes and those tetrapods that share a more recent common ancestor with amniotes than with living amphibians (lissamphibians). It was defined by Michel Laurin (2001) and Vallin and Laurin (2004) as the largest clade that includes Homo sapiens, but not Ascaphus truei. Laurin and Reisz (2020) defined Pan-Amniota as the largest total clade containing Homo sapiens, but not Pipa pipa, Caecilia tentaculata, and Siren lacertina.

Anthracosauria is an order of extinct reptile-like amphibians that flourished during the Carboniferous and early Permian periods, although precisely which species are included depends on one's definition of the taxon. "Anthracosauria" is sometimes used to refer to all tetrapods more closely related to amniotes such as reptiles, mammals, and birds, than to lissamphibians such as frogs and salamanders. An equivalent term to this definition would be Reptiliomorpha. Anthracosauria has also been used to refer to a smaller group of large, crocodilian-like aquatic tetrapods also known as embolomeres.

Pareiasaurs are an extinct clade of large, herbivorous parareptiles. Members of the group were armoured with osteoderms which covered large areas of the body. They first appeared in southern Pangea during the Middle Permian, before becoming globally distributed during the Late Permian. Pareiasaurs were the largest reptiles of the Permian, reaching sizes equivalent to those of contemporary therapsids. Pareiasaurs became extinct in the Permian–Triassic extinction event.

A grade is a taxon united by a level of morphological or physiological complexity. The term was coined by British biologist Julian Huxley, to contrast with clade, a strictly phylogenetic unit.

Avicephala is a potentially polyphyletic grouping of extinct diapsid reptiles that lived during the Late Permian and Triassic periods characterised by superficially bird-like skulls and arboreal lifestyles. As a clade, Avicephala is defined as including the gliding weigeltisaurids and the arboreal drepanosaurs to the exclusion of other major diapsid groups. This relationship is not recovered in the majority of phylogenetic analyses of early diapsids and so Avicephala is typically regarded as an artificial or unnatural grouping. However, the clade was recovered again in 2021 following a redescription of Weigeltisaurus, raising the possibility that the clade may be valid after all, although subsequent analyses have not supported this result.

Procolophonia is an extinct suborder (clade) of herbivorous reptiles that lived from the Middle Permian till the end of the Triassic period. They were originally included as a suborder of the Cotylosauria but are now considered a clade of Parareptilia. They are closely related to other generally lizard-like Permian reptiles such as the Millerettidae, Bolosauridae, Acleistorhinidae, and Lanthanosuchidae, all of which are included under the Anapsida or "Parareptiles".

Younginiformes is a group of diapsid reptiles known from the Permian-Triassic of Africa and Madagascar. It has been used as a replacement for "Eosuchia". Younginiformes were historically suggested to be lepidosauromorphs, but were later suggested to be basal non-saurian neodiapsids. The group is sometimes divided into two families, Tangasauridae and Younginidae. The monophyly of the group is disputed. A 2009 study found them to be an unresolved polytomy at the base of Neodiapsida, while a 2011 study recovered the group as paraphyletic. A 2022 study recovered the Younginiformes as a monophyletic group of basal neodiapsid reptiles, also including Claudiosaurus and Saurosternon as part of the group. Some younginiforms like Hovasaurus and Acerosodontosaurus are thought to have had an amphibious lifestyle, while others like Kenyasaurus, Thadeosaurus and Youngina were probably terrestrial.

Phylogenetic nomenclature is a method of nomenclature for taxa in biology that uses phylogenetic definitions for taxon names as explained below. This contrasts with the traditional method, by which taxon names are defined by a type, which can be a specimen or a taxon of lower rank, and a description in words. Phylogenetic nomenclature is regulated currently by the International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature (PhyloCode).

Pantestudines or Pan-Testudines is the proposed group of all reptiles more closely related to turtles than to any other living animal. It includes both modern turtles and all of their extinct relatives. Pantestudines with a complete shell are placed in the clade Testudinata.

Kevin de Queiroz is a vertebrate, evolutionary, and systematic biologist. He has worked in the phylogenetics and evolutionary biology of squamate reptiles, the development of a unified species concept and of a phylogenetic approach to biological nomenclature, and the philosophy of systematic biology.

References

- Estes, R.; de Queiroz, K. & Gauthier, Jacques (1988): Phylogenetic relationships within Squamata. In:Estes, R. & Pregill, G. (eds.): The Phylogenetic Relationships of the Lizard Families: 15–98. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto.

- Gauthier, Jacques A. (1982): Fossil xenosaurid and anguid lizards from the early Eocene of Wyoming, and a revision of the Anguioidea. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming21: 7-54.

- Gauthier, Jacques A. (1984): A cladistic analysis of the higher systematic categories of the Diapsida. [PhD dissertation]. Available from University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, #85-12825, vii + 564 pp.

- Gauthier, J. A. (1986), "Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds", in Padian, K. (ed.), The Origin of Birds and the Evolution of Flight, Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences, vol. 8, Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences, pp. 1–55, ISBN 0-940228-14-9

- Gauthier, Jacques A.; Estes, R. & de Queiroz, Kevin (1988): A phylogenetic analysis of Lepidosauromorpha. In:Estes, R. & Pregill, G. (eds.): The Phylogenetic Relationships of the Lizard Families: 15–98. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto.

- Gauthier, J. A.; Kluge, A. G.; Rowe, T. (June 1988). "Amniote phylogeny and the importance of fossils" (PDF). Cladistics . 4 (2). John Wiley & Sons: 105–209. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1988.tb00514.x. hdl: 2027.42/73857 . PMID 34949076. S2CID 83502693.

- Rowe, T. & Gauthier, Jacques (1990): Ceratosauria. In:Weishample, D.; Dodson, P. & Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria: 151–168. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- de Queiroz, Kevin & Gauthier, Jacques A. (1992): Phylogenetic taxonomy. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 23: 449–480.

- Gauthier, Jacques A. (1994): The diversification of the amniotes. In:Prothero, D. (ed.): Major Features of Vertebrate Evolution: Short Courses in Paleontology: 129–159. Paleontological Society.

- Donoghue, M. J.; Gauthier, Jacques A. (June 2004). "Implementing the PhyloCode" (PDF). Trends Ecol. Evol. 19 (6): 281–282. Bibcode:2004TEcoE..19..281D. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.04.004. PMID 16701272. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-01. Retrieved 2010-09-26.