This article needs additional citations for verification .(March 2011) |

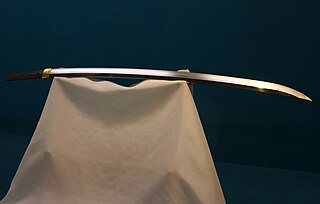

Sword polishing is part of Japanese swordsmithing where a blade is polished after forging. It gives the shining appearance and beauty to the sword.

This article needs additional citations for verification .(March 2011) |

Sword polishing is part of Japanese swordsmithing where a blade is polished after forging. It gives the shining appearance and beauty to the sword.

When the rough blade is completed, the swordsmith turns the blade over to a polisher called a togishi , whose job it is to refine the shape of a blade and improve its aesthetic value. The entire process takes considerable time, in some cases easily up to several weeks. Early polishers used three types of stone, whereas a modern polisher generally uses seven. The modern high level of polish was not normally done before around 1600, since greater emphasis was placed on function over form. The polishing process almost always takes longer than even crafting, and a good polish can greatly improve the beauty of a blade, while a bad one can ruin the best of blades. More importantly, inexperienced polishers can permanently ruin a blade by badly disrupting its geometry or wearing down too much steel, both of which effectively destroy the sword's monetary, historic, artistic, and functional value.

On high quality blades, only the back of the blade and the adjacent sides (called the shinogi-ji), are polished to a mirror-like surface. To bring out the grain and hamon, the center portion of the blade (called the hira), and the edge (the ha), are usually given a matte finish. Microscopic scratches in the surface vary, depending on hardness. Smaller but more numerous scratches in the harder areas reflect light differently from the deeper, longer scratches in the softer areas. The harder metal appears more matte than the softer, and the manner in which it scatters light is less affected by the direction of the lighting. [1]

The process is divided into two stages: Shitaji togi (Foundation polishing) and Shiage togi (Finish polishing).

Shitaji togi sets the geometry of the blade and encompasses all main stages; utilizing large waterstones of increasingly finer grit. The sword is first inspected for straightness: If it isn't straight for whatever reasons, the duty of correcting it falls to the polisher. Straightening usually involves using wooden jigs to correct any bends in the blade. From this point on, a polisher works to form and grind surfaces and geometry as needed; note that these stages are also where damage is repaired through careful reshaping. The relatively small point area of the blade, the kissaki, is distinct enough that it must be worked on by dividing the polishing among smaller subregions. Any present hi (fullers) are also polished but not with the large main stones, instead a variety of methods are used including smaller-sized stones, a migaki-bo (hardened-steel burnishing needle) or even fine-grit sandpaper.

Artificial waterstones are nowadays used for the foundation polishing stage, but almost never used for finishing, as they will produce inferior results compared to natural stones.

Shiage togi is the stage that places the mirrorlike finish on a blade; the most notable differences between this and the previous stage are that the stones are of considerably smaller size, and that the blade remains stationary, instead having the abrasives and tools moved over it. In this stage, a blade is painstakingly worked on section by section, using wafer-thin slices cut from the main stones. After this is done, the blade's look will still be slightly unbalanced, and is corrected with a special nugui mixture that adjusts it. This stage is also where the yokote line is brought out; it may be either artificial or following the existing line (more often than not however, they are usually lost during a prior polishing stage). The final major step involves fully burnishing the rear and sides.

The finishing process brings out and enhances all details of a blade so that they are readily visible for observation and analysis, which entails results that must be free of any visual imperfections.

The nakago is traditionally not polished and only partially finished with file marks, before being allowed to oxidize naturally. The file marks are to provide a friction-fit for the tsuka. The division line between the file markings and the highly polished blade are the machi and two ledges, the ha machi (blade junction – edge side), and the mune machi (blade junction – spine side), around which the fitted habaki is clasped. [2]

There are two main styles of hamon finishes, "hadori" and "sashikomi nugui".

The hadori style is named after the hadori stone used, a waterstone selected for its slightly greater coarseness which helps lighten the hamon and make it stand out against surrounding areas. The hadori style cannot exactly replicate the hamon as the finishing is actually a trace of the original; thus its quality depends mainly on the nature of the hamon itself, available equipment and the skill of the polisher. This process is relatively new, having been developed in the past century.

The sashikomi nugui style is named after the nugui mixture used to produce the final effect. First, the entire hamon is run over by a hazuya stone, a process which also is done to the jihada as well. Next a jizuya stone is used to bring out the hada or grain of the blade. Sashikomi nugui is usually composed of magnetite or tsushima and other compounds depending upon the desired color for the jihada. The nugui mixture is applied to the whole blade and if properly done, the hamon will whiten slightly but surrounding areas will darken considerably. In this case, the hamon's appearance is exactly preserved. This process is normally only done on blades with well-defined hamons and grain patterns.

Polishing is a crucial step in preparing a blade for analysis, since it brings out and enhances all external details as mentioned earlier. This is important because details such as the shape, geometry, particular proportions, appearance of the hamon and grain pattern and so on, are distinctive enough that they can be used to accurately determine the heritage and origin of a blade. As such, they can be considered a more trustworthy signature of a smith than the actual signature itself.

A good polishing reveals what speed the edge was cooled at, from what temperature, and what the carbon content of the steel is. It does this by displaying either predominantly nioi (匂), which is a mix of extremely fine martensite with troostite (another type of tempered steel), or the larger martensite crystals called nie (錵), which look like individual dot-like mirrors.

A Japanese sword is one of several types of traditionally made swords from Japan. Bronze swords were made as early as the Yayoi period, though most people generally refer to the curved blades made from the Heian period to the present day when speaking of "Japanese swords". There are many types of Japanese swords that differ by size, shape, field of application and method of manufacture. Some of the more commonly known types of Japanese swords are the uchigatana, tachi, odachi, wakizashi, and tantō.

Differential heat treatment is a technique used during heat treating of steel to harden or soften certain areas of an object, creating a difference in hardness between these areas. There are many techniques for creating a difference in properties, but most can be defined as either differential hardening or differential tempering. These were common heat treatment techniques used historically in Europe and Asia, with possibly the most widely known example being from Japanese swordsmithing. Some modern varieties were developed in the twentieth century as metallurgical knowledge and technology rapidly increased.

Heat treating is a group of industrial, thermal and metalworking processes used to alter the physical, and sometimes chemical, properties of a material. The most common application is metallurgical. Heat treatments are also used in the manufacture of many other materials, such as glass. Heat treatment involves the use of heating or chilling, normally to extreme temperatures, to achieve the desired result such as hardening or softening of a material. Heat treatment techniques include annealing, case hardening, precipitation strengthening, tempering, carburizing, normalizing and quenching. Although the term heat treatment applies only to processes where the heating and cooling are done for the specific purpose of altering properties intentionally, heating and cooling often occur incidentally during other manufacturing processes such as hot forming or welding.

An abrasive is a material, often a mineral, that is used to shape or finish a workpiece through rubbing which leads to part of the workpiece being worn away by friction. While finishing a material often means polishing it to gain a smooth, reflective surface, the process can also involve roughening as in satin, matte or beaded finishes. In short, the ceramics which are used to cut, grind and polish other softer materials are known as abrasives.

Tumble finishing, also known as tumbling or rumbling, is a technique for smoothing and polishing a rough surface on relatively small parts. In the field of metalworking, a similar process called barreling, or barrel finishing, works upon the same principles.

Gorō Nyūdō Masamune, was a medieval Japanese blacksmith widely acclaimed as Japan's greatest swordsmith. He created swords and daggers, known in Japanese as tachi and tantō, in the Sōshū school. However, many of his forged tachi were made into katana by cutting the tang (nakago) in later times ("suriage"). For this reason, his only existing works are katana and tantō. No exact dates are known for Masamune's life. It is generally agreed that he made most of his swords between 1288 and 1328. Some stories list his family name as Okazaki, but some experts believe this is a fabrication to enhance the standing of the Tokugawa family.

The iaitō (居合刀) is a modern metal practice sword, without a cutting edge, used primarily for practicing iaido, a form of Japanese swordsmanship.

Tempering is a process of heat treating, which is used to increase the toughness of iron-based alloys. Tempering is usually performed after hardening, to reduce some of the excess hardness, and is done by heating the metal to some temperature below the critical point for a certain period of time, then allowing it to cool in still air. The exact temperature determines the amount of hardness removed, and depends on both the specific composition of the alloy and on the desired properties in the finished product. For instance, very hard tools are often tempered at low temperatures, while springs are tempered at much higher temperatures.

Sword making, historically, has been the work of specialized smiths or metalworkers called bladesmiths or swordsmiths. Swords have been made of different materials over the centuries, with a variety of tools and techniques. While there are many criteria for evaluating a sword, generally the four key criteria are hardness, strength, flexibility and balance. Early swords were made of copper, which bends easily. Bronze swords were stronger; by varying the amount of tin in the alloy, a smith could make various parts of the sword harder or tougher to suit the demands of combat service. The Roman gladius was an early example of swords forged from blooms of steel.

French polishing is a wood finishing technique that results in a very high gloss surface, with a deep colour and chatoyancy. French polishing consists of applying many thin coats of shellac dissolved in denatured alcohol using a rubbing pad lubricated with one of a variety of oils. The rubbing pad is made of absorbent cotton or wool cloth wadding inside of a piece of fabric and is commonly referred to as a fad, also called a rubber, tampon, or muñeca.

Knife making is the process of manufacturing a knife by any one or a combination of processes: stock removal, forging to shape, welded lamination or investment cast. Typical metals used come from the carbon steel, tool, or stainless steel families. Primitive knives have been made from bronze, copper, brass, iron, obsidian, and flint.

Knife sharpening is the process of making a knife or similar tool sharp by grinding against a hard, rough surface, typically a stone, or a flexible surface with hard particles, such as sandpaper. Additionally, a leather razor strop, or strop, is often used to straighten and polish an edge.

Polishing and buffing are finishing processes for smoothing a workpiece's surface using an abrasive and a work wheel or a leather strop. Technically, polishing refers to processes that uses an abrasive that is glued to the work wheel, while buffing uses a loose abrasive applied to the work wheel. Polishing is a more aggressive process, while buffing is less harsh, which leads to a smoother, brighter finish. A common misconception is that a polished surface has a mirror-bright finish, however, most mirror-bright finishes are actually buffed.

In swordsmithing, hamon (刃文) is a visible effect created on the blade by the hardening process. The hamon is the outline of the hardened zone which contains the cutting edge. Blades made in this manner are known as differentially hardened, with a harder cutting edge than spine. This difference in hardness results from clay being applied on the blade prior to the cooling process (quenching). Less or no clay allows the edge to cool faster, making it harder but more brittle, while more clay allows the center and spine to cool slower, thus retaining its resilience.

Japanese swordsmithing is the labour-intensive bladesmithing process developed in Japan beginning in the sixth century for forging traditionally made bladed weapons (nihonto) including katana, wakizashi, tantō, yari, naginata, nagamaki, tachi, nodachi, ōdachi, kodachi, and ya (arrow).

Honyaki (本焼) is the name for the Japanese traditional method of metalwork construction most often seen in kitchen knives by forging a blade, with a technique most similar to the tradition of nihonto, from a single piece of high-carbon steel covered with clay to yield upon quench a soft, resilient spine, a hamon, and a hard, sharp edge. Honyaki as a term alone can refer to either mizu honyaki (water-quench) or abura honyaki. The goal is to produce a sharper, longer lasting edge than is usually achievable with the lamination method. The term has been adapted to describe high-end mono-stainless in Japan and carbon blades by non-Japanese bladesmiths that have a hamon but are made with Western steel, heat treat, equipment, finishing, and design.

A katana is a Japanese sword characterized by a curved, single-edged blade with a circular or squared guard and long grip to accommodate two hands. Developed later than the tachi, it was used by samurai in feudal Japan and worn with the edge facing upward. Since the Muromachi period, many old tachi were cut from the root and shortened, and the blade at the root was crushed and converted into a katana. The specific term for katana in Japan is uchigatana (打刀) and the term katana (刀) often refers to single-edged swords from around the world.

Mass finishing is a group of manufacturing processes that allow large quantities of parts to be simultaneously finished. The goal of this type of finishing is to burnish, deburr, clean, radius, de-flash, descale, remove rust, polish, brighten, surface harden, prepare parts for further finishing, or break off die cast runners. The two main types of mass finishing are tumble finishing, also known as barrel finishing, and vibratory finishing. Both involve the use of a cyclical action to create grinding contact between surfaces. Sometimes the workpieces are finished against each other; however, usually a finishing medium is used. Mass finishing can be performed dry or wet; wet processes have liquid lubricants, cleaners, or abrasives, while dry processes do not. Cycle times can be as short as 10 minutes for nonferrous workpieces or as long as 2 hours for hardened steel.

This is the glossary of Japanese swords, including major terms the casual reader might find useful in understanding articles on Japanese swords. Within definitions, words set in boldface are defined elsewhere in the glossary.