This is the glossary of Japanese swords, including major terms the casual reader might find useful in understanding articles on Japanese swords. Within definitions, words set in boldface are defined elsewhere in the glossary.

This is the glossary of Japanese swords, including major terms the casual reader might find useful in understanding articles on Japanese swords. Within definitions, words set in boldface are defined elsewhere in the glossary.

A Japanese sword is one of several types of traditionally made swords from Japan. Bronze swords were made as early as the Yayoi period, though most people generally refer to the curved blades made from the Heian period (794–1185) to the present day when speaking of "Japanese swords". There are many types of Japanese swords that differ by size, shape, field of application and method of manufacture. Some of the more commonly known types of Japanese swords are the uchigatana, tachi, ōdachi, wakizashi, and tantō.

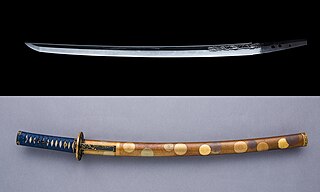

A tachi is a type of sabre-like traditionally made Japanese sword (nihonto) worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. Tachi and uchigatana generally differ in length, degree of curvature, and how they were worn when sheathed, the latter depending on the location of the mei (銘), or signature, on the tang. The tachi style of swords preceded the development of the katana, which was not mentioned by name until near the end of the twelfth century. Tachi were the mainstream Japanese swords of the Kotō period between 900 and 1596. Even after the Muromachi period (1336–1573), when katana became the mainstream, tachi were often worn by high-ranking samurai.

The wakizashi is one of the traditionally made Japanese swords worn by the samurai in feudal Japan. Its name refers to the practice of wearing it inserted through one's obi or sash at one's side, whereas the larger tachi sword was worn slung from a cord.

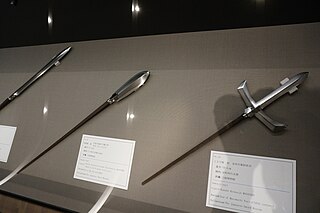

Yari (槍) is the term for a traditionally-made Japanese blade in the form of a spear, or more specifically, the straight-headed spear. The martial art of wielding the yari is called sōjutsu.

A tantō is one of the traditionally made Japanese swords that were worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The tantō dates to the Heian period, when it was mainly used as a weapon but evolved in design over the years to become more ornate. Tantō were used in traditional martial arts. The term has seen a resurgence in the West since the 1980s as a point style of modern tactical knives, designed for piercing or stabbing.

Gorō Nyūdō Masamune was a medieval Japanese blacksmith widely acclaimed as Japan's greatest swordsmith. He created swords and daggers, known in Japanese as tachi and tantō, in the Sōshū school. However, many of his forged tachi were made into katana by cutting the tang (nakago) in later times ("suriage"). For this reason, his only existing works are katana, tantō, and wakizashi. No exact dates are known for Masamune's life. It is generally agreed that he made most of his swords between 1288 and 1328. Some stories list his family name as Okazaki, but some experts believe this is a fabrication to enhance the standing of the Tokugawa family.

Muramasa, commonly known as Sengo Muramasa (千子村正), was a famous swordsmith who founded the Muramasa school and lived during the Muromachi period in Kuwana, Ise Province, Japan.

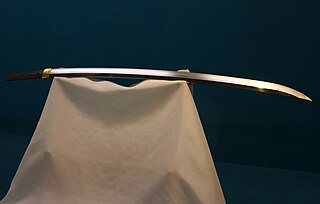

The ōdachi (大太刀) or nodachi is a type of traditionally made Japanese sword used by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The Chinese equivalent of this type of sword in terms of weight and length is the miaodao or the earlier zhanmadao, and the Western battlefield equivalent is the Zweihänder.

The iaitō (居合刀) is a modern metal practice sword, without a cutting edge, used primarily for practicing iaido, a form of Japanese swordsmanship.

The chokutō is a straight, single-edged Japanese sword that was mainly produced prior to the 9th century. Its basic style is likely derived from similar swords of ancient China. Chokutō were used on foot for stabbing or slashing and were worn hung from the waist. Until the Heian period such swords were called tachi (大刀), which should not be confused with tachi written as 太刀 referring to curved swords.

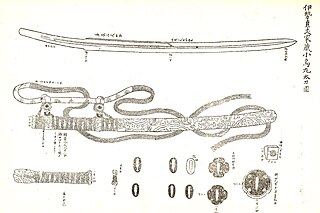

Japanese sword mountings are the various housings and associated fittings that hold the blade of a Japanese sword when it is being worn or stored. Koshirae (拵え) refers to the ornate mountings of a Japanese sword used when the sword blade is being worn by its owner, whereas the shirasaya is a plain undecorated wooden mounting composed of a saya and tsuka that the sword blade is stored in when not being used.

The Kogarasu Maru (小烏丸), or "Little Crow Circle", is a unique Japanese tachi sword believed to have been created by legendary Japanese smith Amakuni during the 8th century AD.

In swordsmithing, hamon (刃文) is a visible effect created on the blade by the hardening process. The hamon is the outline of the hardened zone which contains the cutting edge. Blades made in this manner are known as differentially hardened, with a harder cutting edge than spine. This difference in hardness results from clay being applied on the blade prior to the cooling process (quenching). Less or no clay allows the edge to cool faster, making it harder but more brittle, while more clay allows the center and spine to cool slower, thus retaining its resilience.

Japanese swordsmithing is the labour-intensive bladesmithing process developed in Japan beginning in the sixth century for forging traditionally made bladed weapons (nihonto) including katana, wakizashi, tantō, yari, naginata, nagamaki, tachi, nodachi, ōdachi, kodachi, and ya (arrow).

Hoko yari is an ancient form of Japanese spear or yari said to be based on a Chinese spear. The hoko yari came into use sometime between the Yayoi period and the Heian period, possibly during the Nara period in the 8th century AD.

The yoroi-dōshi (鎧通し), "armor piercer" or "mail piercer", is one of the traditionally made Japanese swords that were worn by the samurai class as a weapon in feudal Japan.

A katana is a Japanese sword characterized by a curved, single-edged blade with a circular or squared guard and long grip to accommodate two hands. Developed later than the tachi, it was used by samurai in feudal Japan and worn with the edge facing upward. Since the Muromachi period, many old tachi were cut from the root and shortened, and the blade at the root was crushed and converted into a katana. The specific term for katana in Japan is uchigatana (打刀) and the term katana (刀) often refers to single-edged swords from around the world.

Sword polishing is part of Japanese swordsmithing where a blade is polished after forging. It gives the shining appearance and beauty to the sword.

The Kara-tachi sword with gilded silver fittings and inlay is an 8th century Japanese sword in the chokutō style. It was one of Emperor Shōmu's favorite swords and was handed down in the Shōsōin Repository.